Quiet change often starts with one stubborn act carried out at the right moment. Fame goes to the loudest names, yet the country is held together by people who made smarter laws, safer medicine, fairer rulings, open parks, and wider runways. Some worked in courts, others in labs or skies or streets. Many paid a price. What they left behind is practical and visible in daily life. Here’s the thing: remembering them is not nostalgia. It is upkeep.

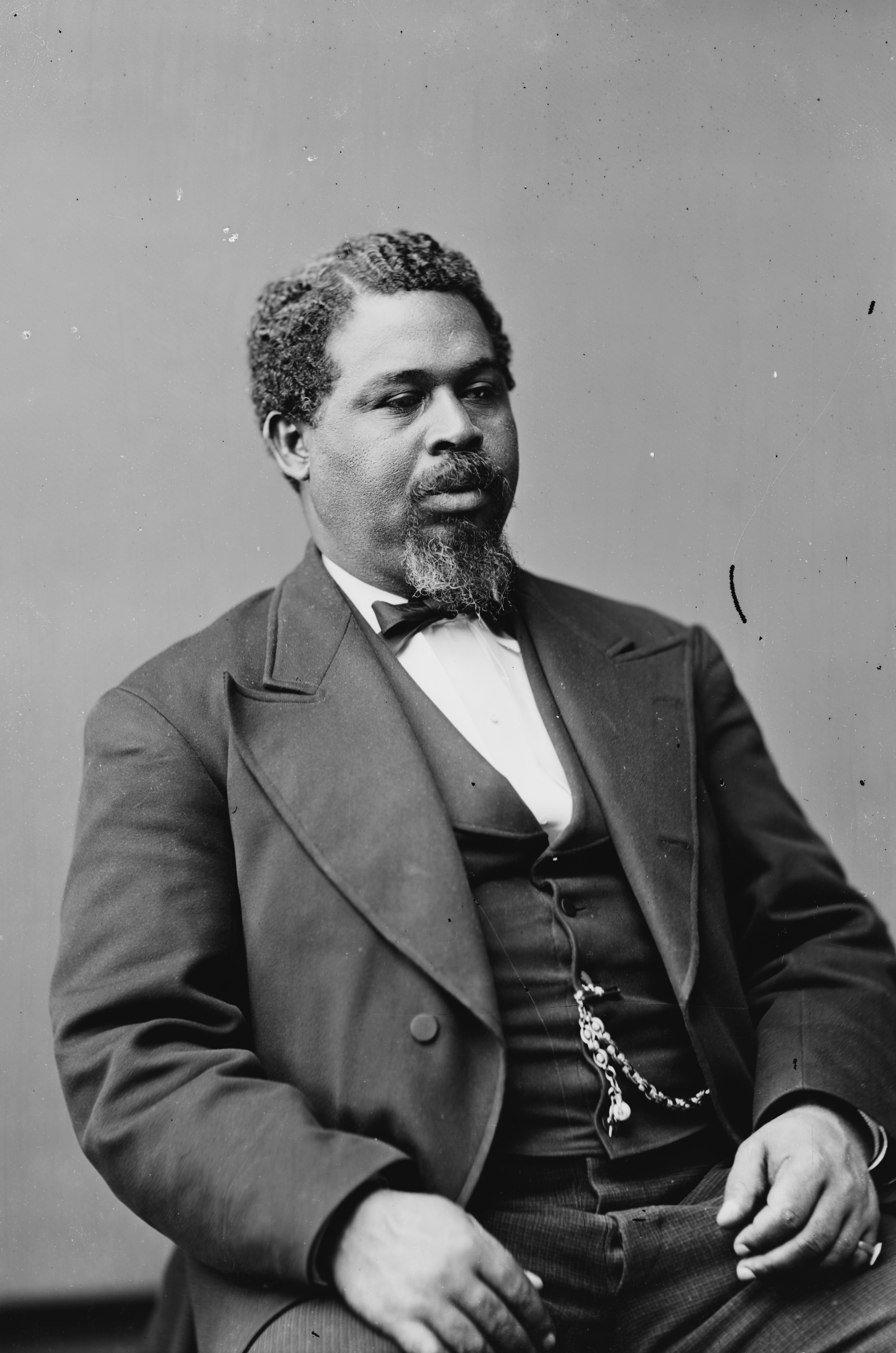

Robert Smalls

In May 1862, Robert Smalls commandeered a Confederate steamer in Charleston Harbor, copied the captain’s signals, and navigated past guard posts to deliver his family and crew to Union lines. The intelligence he handed over reshaped coastal strategy, and his audacity inspired Black enlistment. After the war he served in Congress, opened schools, and defended voting rights. Smalls turned local knowledge into national leverage and proved courage can be planned, not improvised, then repeated for a lifetime.

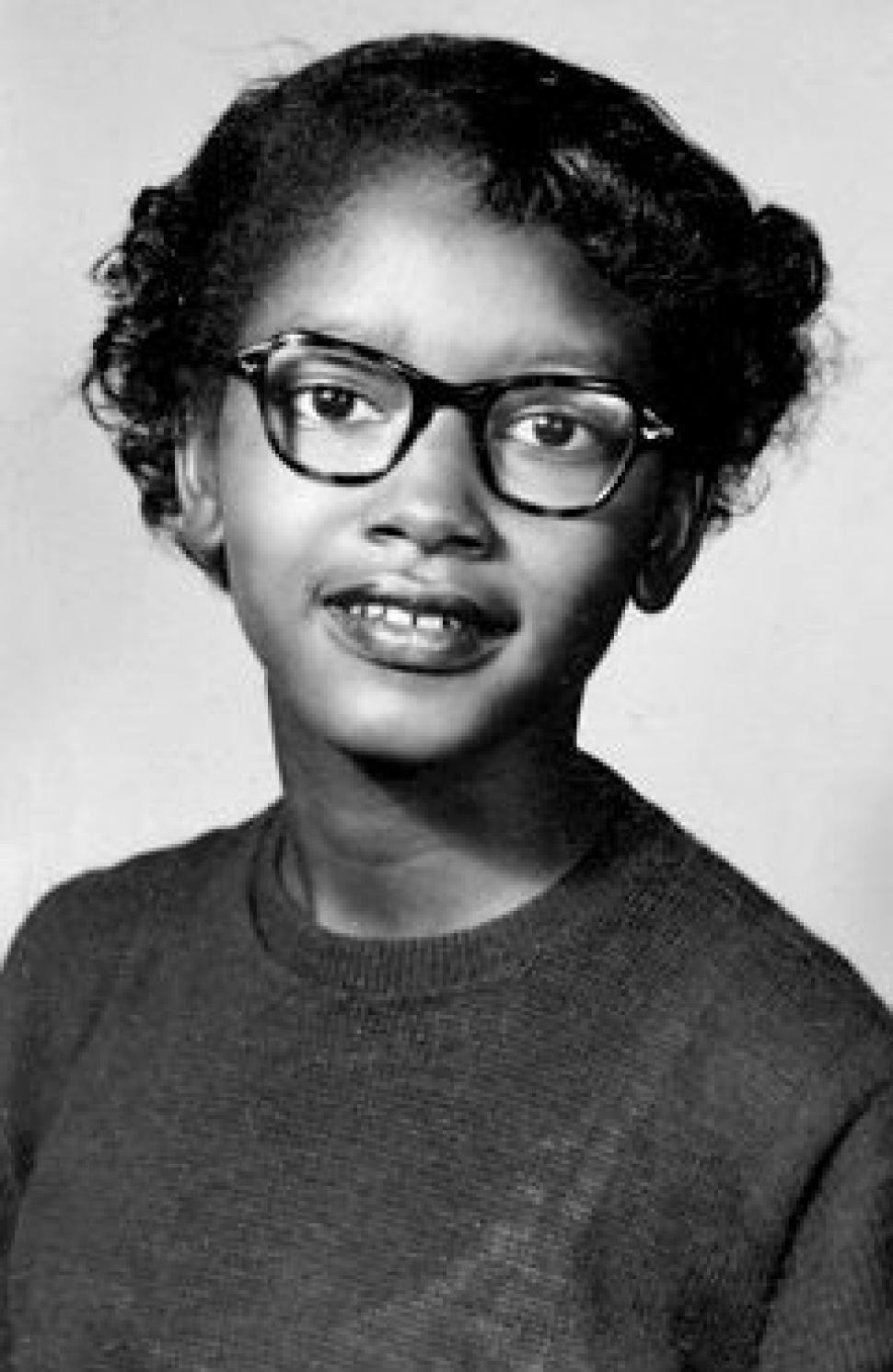

Claudette Colvin

Nine months before the headline moment in Montgomery, fifteen-year-old Claudette Colvin refused to give up her seat and was hauled off a bus for it. Leaders doubted her optics, but the Constitution listened. She became a key plaintiff in Browder v. Gayle, the case that ended bus segregation in Alabama. Colvin’s stand shows movements are built by many hands, not one poster, and that a teenager’s steady no can pry open a locked policy.

Frances Oldham Kelsey

As a new FDA medical officer in 1960, Frances Oldham Kelsey refused to approve thalidomide without solid safety data. Her calm skepticism spared the United States the birth defects that devastated families abroad and drove sweeping reforms in clinical testing and transparency. Kelsey did not grandstand. She asked precise questions until the science held up or fell apart. Public health, in her hands, was a signature withheld until evidence could do the heavy lifting.

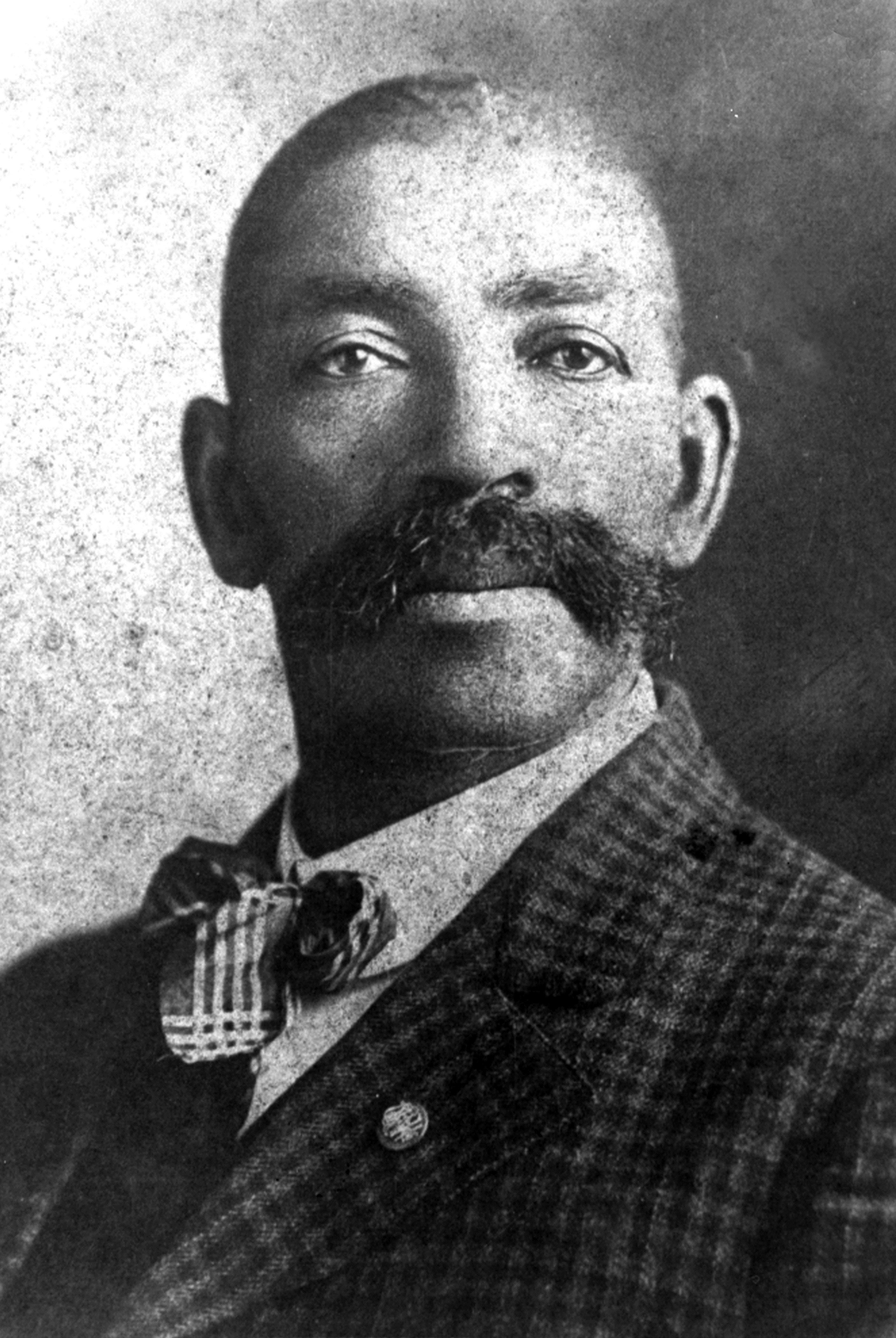

Bass Reeves

Born enslaved and later a U.S. deputy marshal, Bass Reeves roamed Indian Territory with a precise memory, clever disguises, and a rare insistence on warrants over grudges. He is credited with thousands of arrests and a reputation for fairness that outlived legends. Folklore celebrates masked riders, but Reeves did the work unmasked, steady and exact. His story argues that the law can be both firm and just, even at the edges of maps and patience.

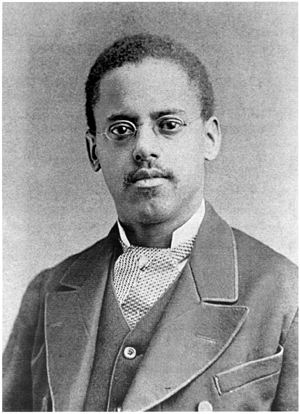

Lewis Latimer

Working with early telephone and lighting pioneers, Lewis Latimer patented a carbon filament that extended bulb life and moved electric light from experiment to everyday utility. He helped design municipal systems and wrote the first manual on electric lighting, translating theory into city blocks and house lamps. Latimer thrived in the overlooked middle where ideas become infrastructure. Streets glow at night because someone solved the part others found tedious and made it repeatable at scale.

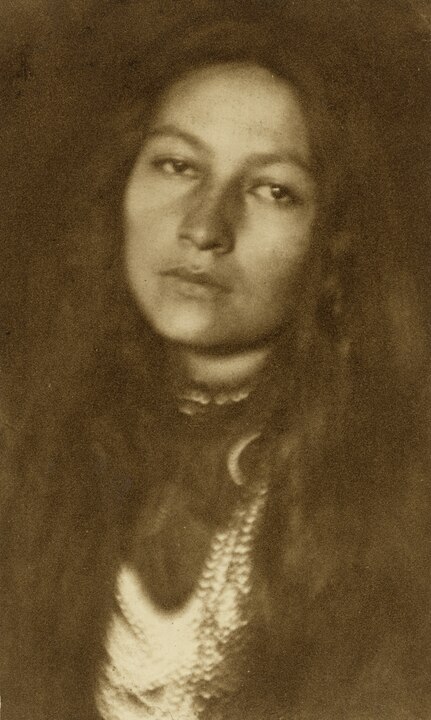

Zitkala Sa

A Yankton Dakota writer, violinist, and organizer, Zitkala Sa turned personal history into sharp essays that cut through policy fog and sentiment. She co-founded a national council to press for Native rights, pushed for citizenship, and challenged abuses in boarding schools. Her art and advocacy were not separate tracks but one road. By playing concert halls and walking into hearings, she forced audiences to meet living culture, not a museum piece, and to act accordingly.

Fred Korematsu

When the government ordered mass incarceration of Japanese Americans, Fred Korematsu resisted and lost at the Supreme Court in 1944. Decades later, hidden evidence of misconduct surfaced, his conviction was vacated, and he spent the rest of his life defending civil liberties in wartime. The lesson is blunt. Fear does not amend the Constitution. Korematsu’s long arc seeded modern skepticism of sweeping security claims and taught courts to demand proof before rights are boxed up.

Bessie Coleman

Shut out of U.S. flight schools by race and gender, Bessie Coleman learned French, trained in Europe, and returned with a pilot’s license and a plan. She barnstormed across the country, thrilling crowds while refusing to perform for segregated audiences. She intended to open a flight school so others would not need a passport to learn. Her life ended too soon, but the message held: keep the runway clear for those who are ready to fly.

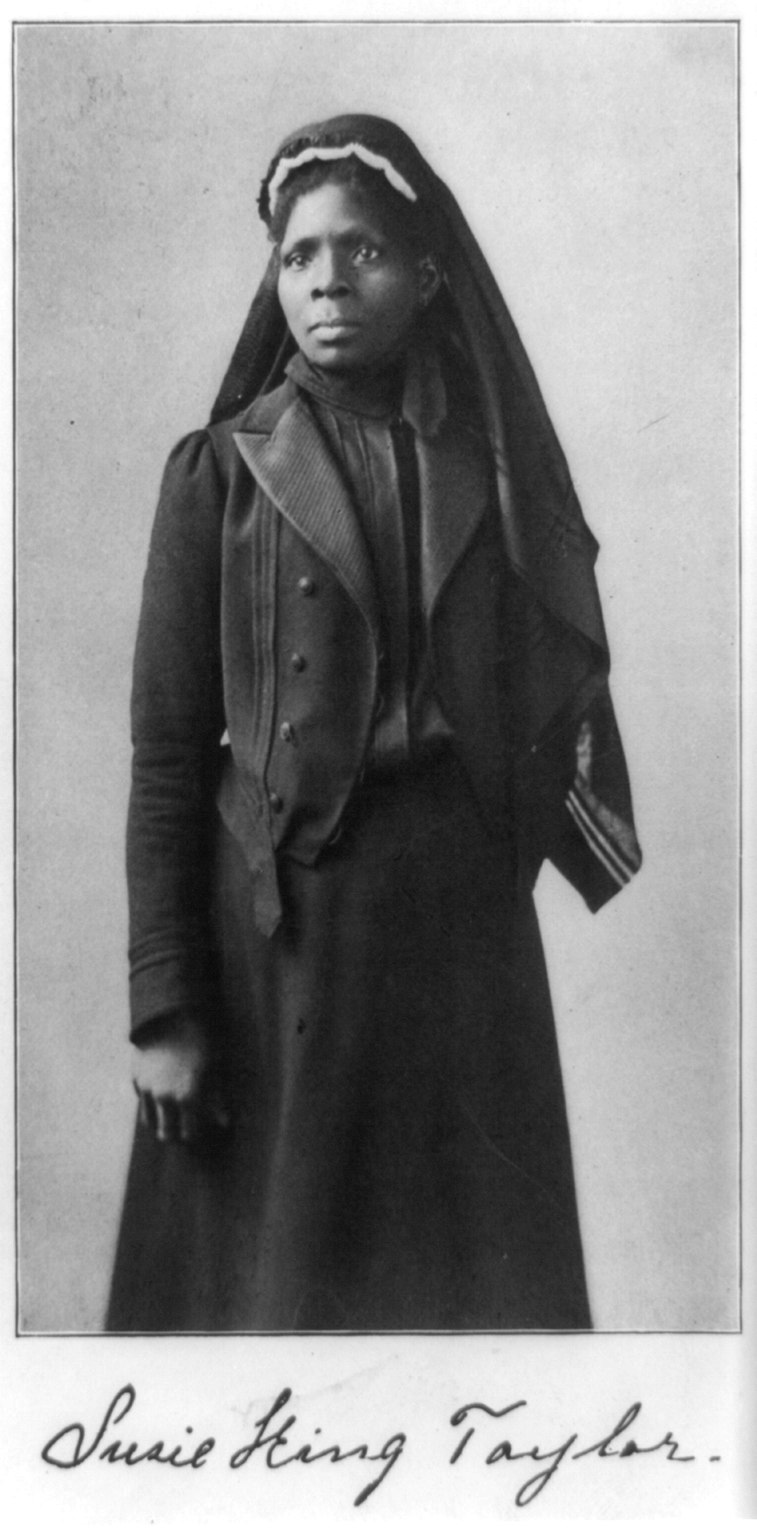

Susie King Taylor

Escaping slavery in Georgia, Susie King Taylor reached Union lines, became a nurse and teacher with the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, and later wrote the only known Civil War memoir by a Black woman. She documented battlefield medicine, hunger, and the daily work of holding dignity together. Her service stitched wounds and literacy at the same time. Read her pages and you see the war from ground level, where survival and purpose share a tent.

Sylvia Rivera

Street organizer, loud and generous, Sylvia Rivera co-founded a group that gave queer and trans youth food, beds, and stubborn care when institutions would not. She fought police harassment and exclusion within the movement, insisting liberation either included everyone or it was just a slogan. Rivera’s politics were practical and demanding. Feed people, shelter people, then change the rules that keep them outside. Many of today’s broader protections trace back to those sidewalk fights.

Standing Bear

In 1879, Ponca Chief Standing Bear went to federal court to assert a simple truth: Native people are persons under the law with the right to their homelands and bodies. The judge agreed, a landmark that pushed against policies treating tribes as wards. It did not fix everything, but it set a legal anchor others tied to later. A plain sentence spoken plainly can reroute policy, then hold firm when the wind rises again.

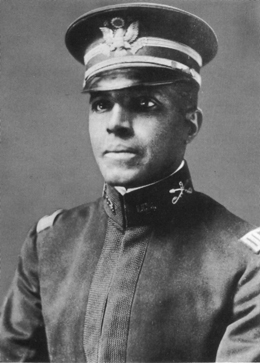

Charles Young

Third Black graduate of West Point, Charles Young rose to colonel, led Buffalo Soldiers, and served as acting superintendent of Sequoia, where his troops cut roads that opened the groves to the public. He later served as a diplomat and intelligence officer, holding standards high across uniforms and assignments. Young’s career linked stewardship, service, and statecraft. The paths tourists drive today were once plans on his desk, then switchbacks carved by patient hands.

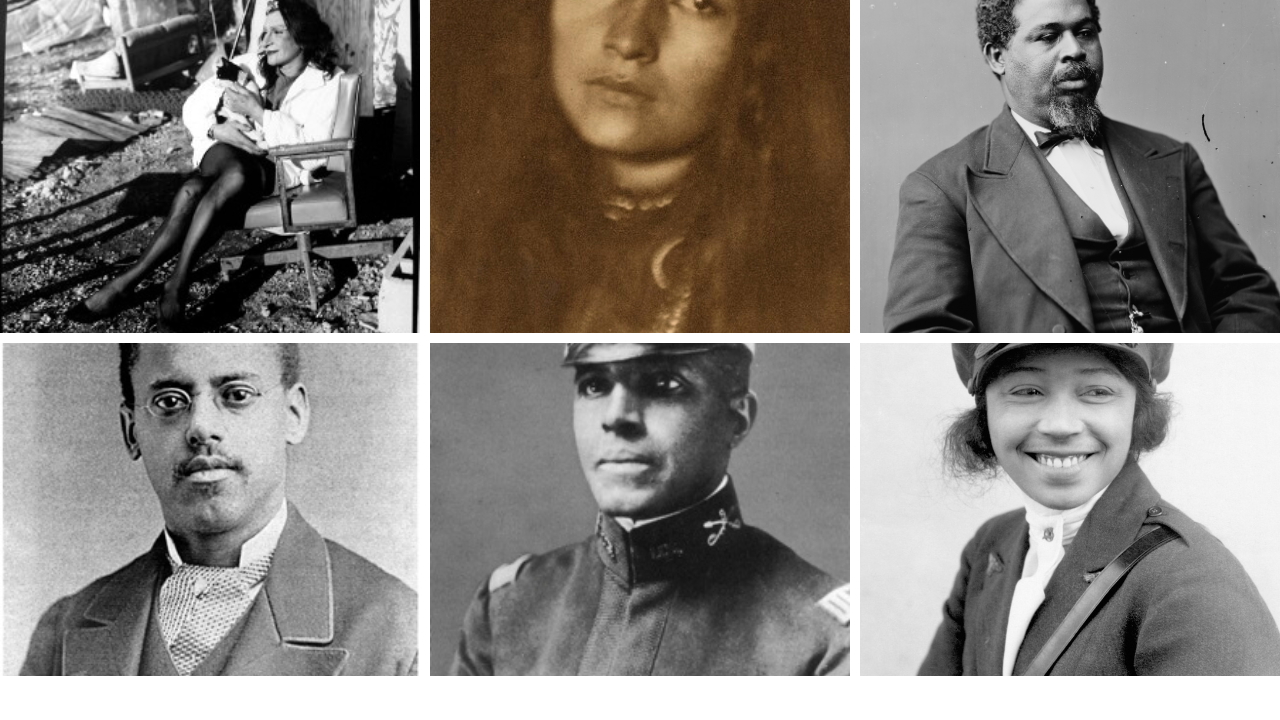

Hazel Scott

A prodigy pianist who moved between classical halls and jazz stages, Hazel Scott used fame to challenge segregation and lazy stereotypes in film. She refused demeaning roles, won a discrimination suit against a restaurant, and later stared down smear tactics during the Red Scare. The pushback cost her momentum, not purpose. Scott set a bar for artistic dignity and then kept playing past those who wanted it lowered. The echo is still in the room.