History often circles around the same handful of names while others who carried real weight slip to the margins. Some of those lives played out in cramped classrooms, muddy trenches, segregated buses, and makeshift airfields, far from cameras or podiums. They challenged laws, rewrote procedures, or simply refused to move when told. Remembering them is not nostalgia; it is maintenance. It keeps the story of the United States closer to the truth, with all its risk, sacrifice, and stubborn hope.

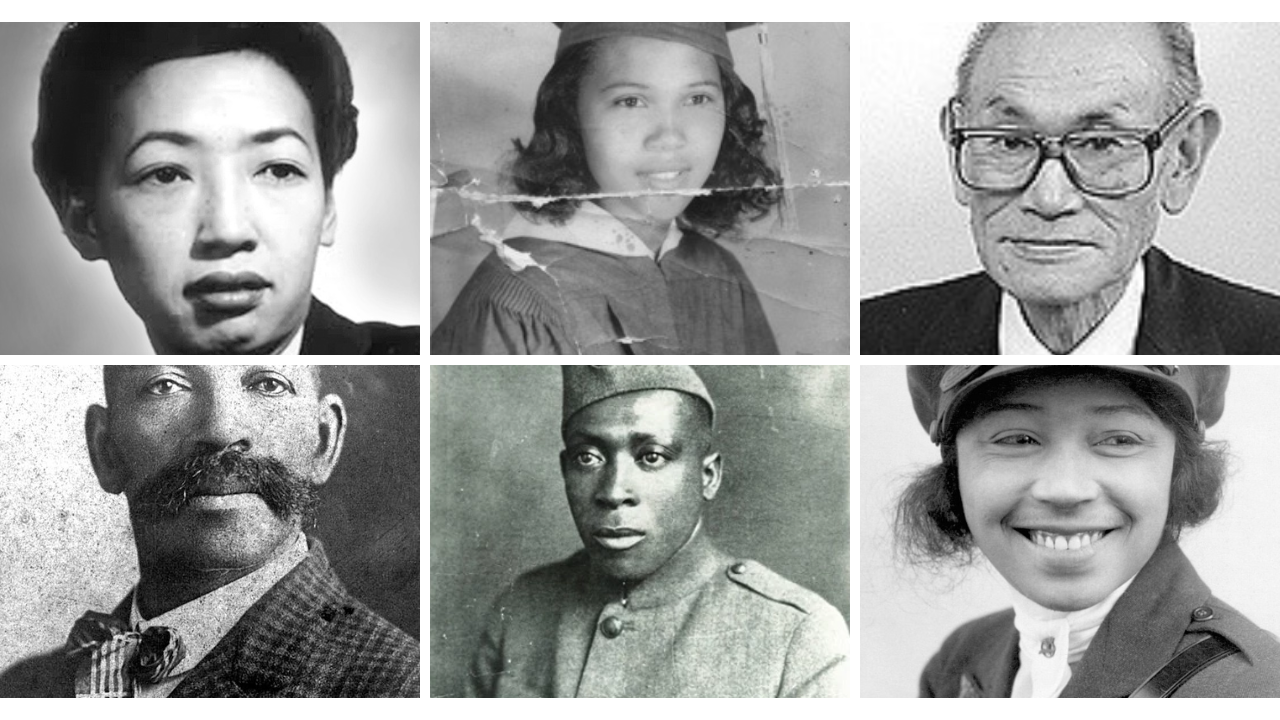

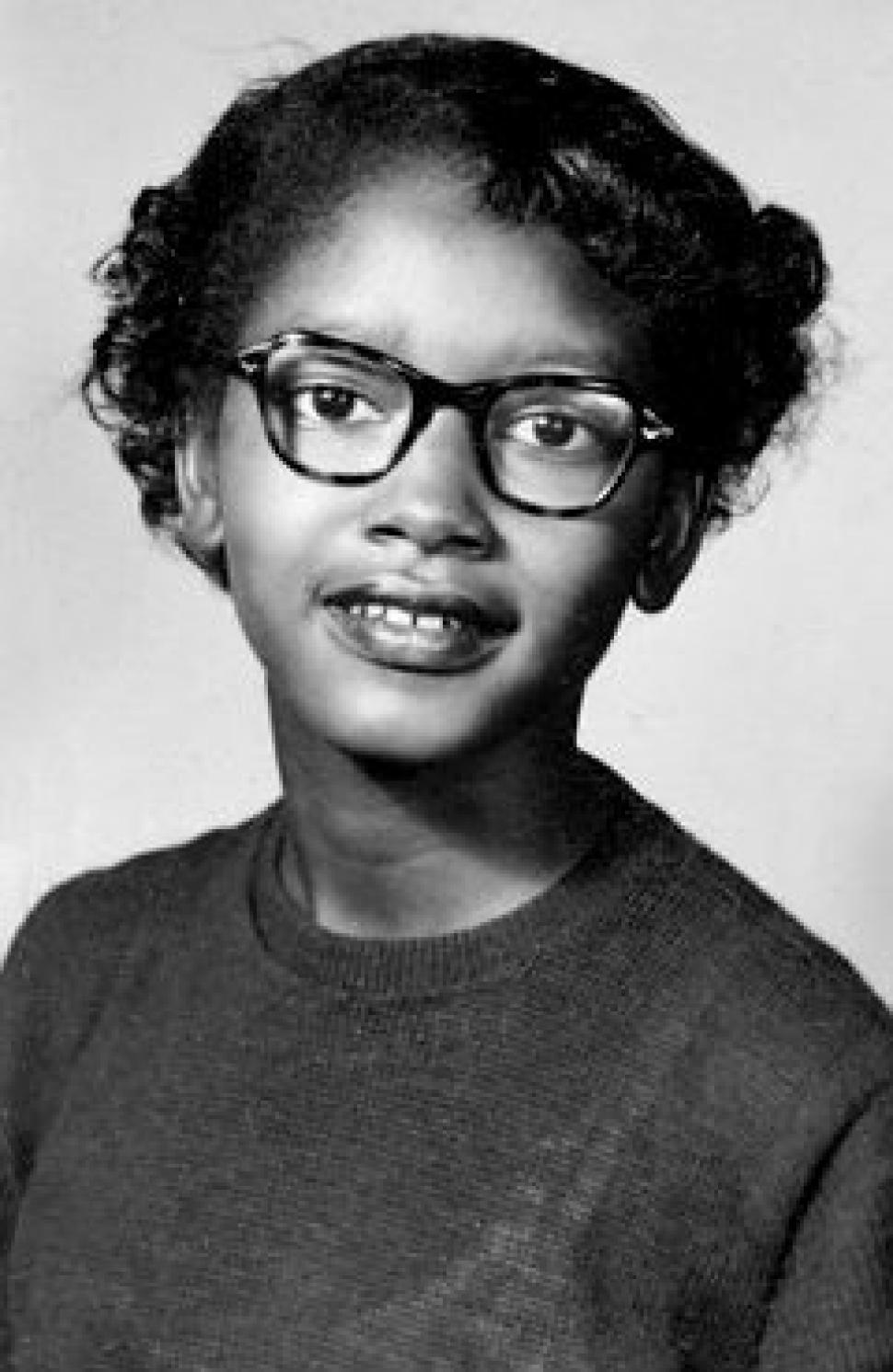

Claudette Colvin

In March 1955, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus, months before Rosa Parks made headlines for the same act. Police dragged her off, jailed her, and local leaders treated her as too young and too controversial to represent the movement. She later became a plaintiff in the case that struck down bus segregation, yet her name rarely appears in schoolbooks, even though her courage helped set the legal groundwork for the civil rights era.

Barbara Johns

At 16, Barbara Johns looked around Robert Russa Moton High School in Farmville, Virginia, and decided the overcrowded, crumbling building was an insult, not an education. In April 1951 she quietly organized a student walkout, filled the auditorium, and led classmates out the doors to demand equal schools. Their protest sparked a lawsuit that joined Brown v. Board of Education, the decision that ended legal school segregation. Johns avoided attention later in life, but her push for dignity set major change in motion.

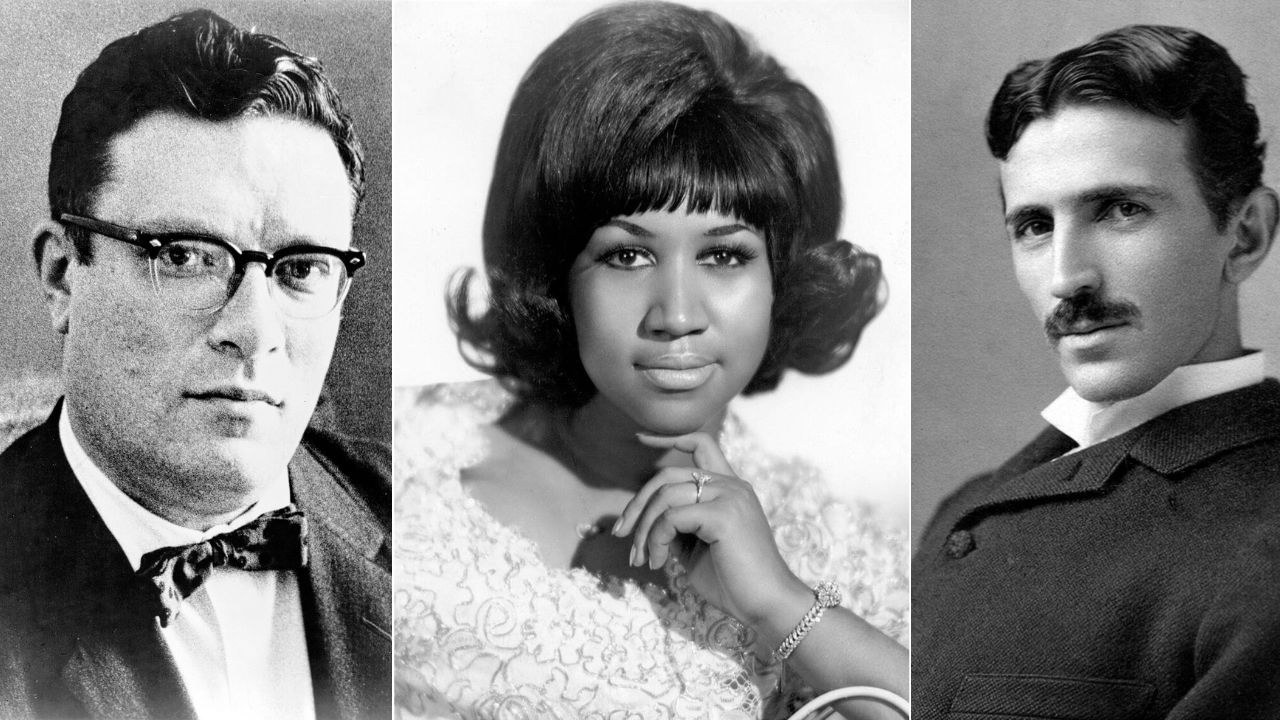

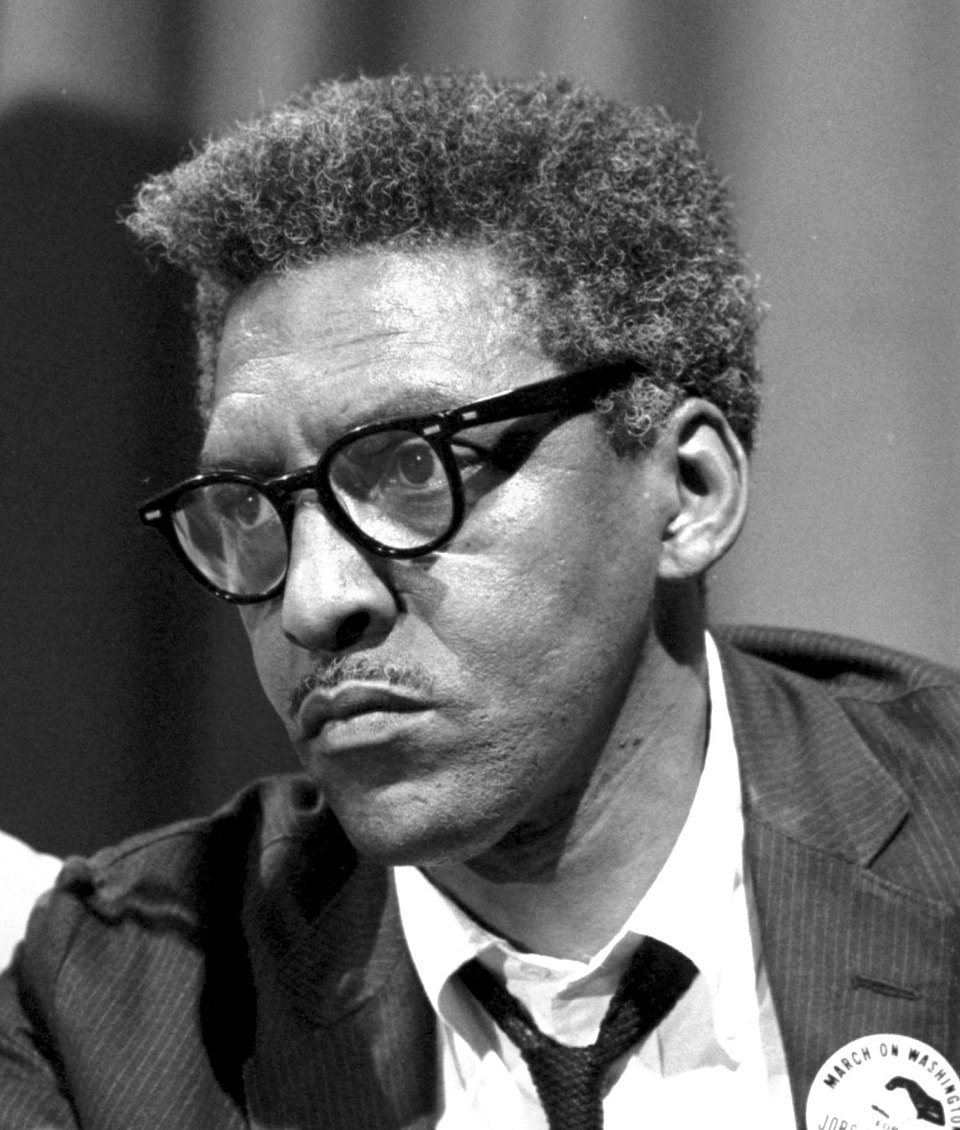

Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin stood behind microphones rather than in front of them, yet his planning shaped the civil rights era. A master strategist of nonviolence, he advised Martin Luther King Jr., helped form key organizations, and served as chief architect of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Because he was gay and once aligned with left-wing groups, allies often hid his role to protect the movement. His influence, steady and brilliant, held major campaigns together when stakes were high.

Hazel Ying Lee

Hazel Ying Lee grew up in Portland, Oregon, dreaming of flight when women and Chinese Americans faced steep barriers in aviation. She scraped together money for lessons, earned her pilot license in 1932, and later joined the Women Airforce Service Pilots during World War II. She ferried powerful aircraft across the country under exhausting schedules and blunt discrimination. A midair collision in 1944 ended her life, and her contributions went largely unrecognized for decades despite breaking both gender and racial ceilings.

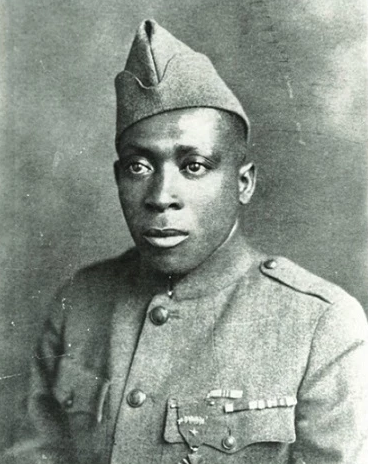

Henry Johnson

Sgt. Henry Johnson of the Harlem Hellfighters stood guard in a French trench in May 1918 when a German raiding party attacked. Wounded and outnumbered, he fought with rifle, grenades, and finally a knife to protect a fellow soldier. France awarded him its highest honor, yet the United States ignored his heroism for decades. He returned to poverty and fading health, only receiving full recognition long after his death. His bravery remains one of the most striking stories of World War I.

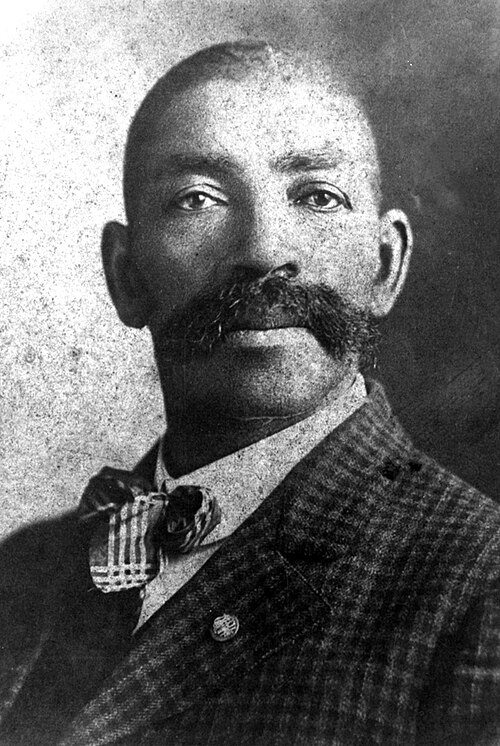

Bass Reeves

Bass Reeves was born enslaved, escaped during the Civil War, and later became one of the first Black deputy U.S. marshals west of the Mississippi. Working across vast stretches of Indian Territory, he tracked fugitives with skill, made thousands of arrests, and earned a reputation for fairness even among those he captured. Popular Western mythology focused on white lawmen, leaving Reeves in the shadows. Renewed attention has finally begun to place him where he belongs: at the center of the real frontier story.

Charles R. Drew

Dr. Charles Drew transformed medicine by figuring out how to store and transport blood plasma safely and efficiently. His innovations powered wartime blood programs and later civilian hospitals, making transfusions far more reliable. He opposed racist policies that separated donated blood by race, arguing they lacked any scientific basis. His life ended suddenly in a car crash in 1950, but his work continues to save lives every day. Few medical pioneers have left such a lasting and practical legacy.

Bessie Coleman

Bessie Coleman rejected the idea that only white men could fly. Blocked from American flight schools, she learned French, traveled abroad, and earned an international pilot license in 1921. She returned home determined to inspire Black Americans by performing daring air shows and raising funds for a flight school open to all. A tragic plane accident in 1926 cut her life short, yet her determination continues to echo through generations of pilots who see her as a model of grit and imagination.

Fred Korematsu

Fred Korematsu stayed in California with his Italian American girlfriend during World War II instead of reporting to an incarceration camp like other Japanese Americans. Arrested and convicted, he became the focus of a Supreme Court case that upheld the government’s sweeping actions. Decades later, suppressed evidence helped overturn his conviction, and he spent his later years speaking against racial profiling and wartime fear. States now honor his birthday as Korematsu Day to keep his message alive.