Royal marriage served strategy first and romance second. Bloodlines doubled as treaties, so cousins became convenient diplomats. Courts prized shared language, predictable alliances, and heirs who kept land inside the map of a single name. Genetics received little thought, yet the costs surfaced over generations. From London to Vienna, palaces approved unions that tightened control, simplified protocol, and sometimes narrowed the cradle. These portraits carry titles and lace, but the margins reveal family trees drawn in tight circles.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert

Victoria and Albert shared a grandfather, Francis of Saxe Coburg Saalfeld, which made them first cousins. Their marriage created a powerful kin network that stretched across Europe, then cracked under world wars when cousins faced cousins. The union blended affection with calculation, placing Coburg ties at the center of British public life. Their many children married into major houses and exported court style, yet the same closeness aided the spread of inherited conditions that modern readers recognize.

King George IV and Caroline of Brunswick

George IV married his first cousin Caroline in 1795 to tidy politics and money, not to build harmony. The match unraveled quickly, and separation followed within a year, while pamphlets and Parliament turned their quarrels into public sport. Kinship did not soften tempers or curb excess, but it did signal Hanoverian cohesion at a delicate moment. The episode shows how court math prized familiar brides, even when the human equation refused to balance after vows were spoken.

King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra

Edward VII followed family habit by wedding Alexandra of Denmark, his third cousin. The tie soothed relations between London and Copenhagen, useful as Europe’s royal houses measured influence by kin counts. Their public presence steadied the crown after a long Victorian shadow, while private life carried its own storms. The cousin link felt ordinary to contemporaries who saw dynasties as extended households. It kept correspondence warm across courts and made protocol glide where strangers might stumble.

King George V and Queen Mary

George V and Mary of Teck were second cousins who shared a great grandparent. The pairing reassured a country that valued continuity through war and reform, and it kept advisers working inside known lanes. Their kinship folded neatly into a story of stability, yet it also thickened the web of relations that later crossed battle lines. In practice, the marriage showed how a narrow marriage market streamlined ceremony, polished duty, and quietly traded genetic diversity for predictability.

Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip

Elizabeth II and Philip were third cousins through Victoria and also linked to Christian IX of Denmark, which made them second cousins once removed by another path. Two pedigrees met on friendly terms, and the result felt both modern and deeply traditional. The connection smoothed introductions from Athens to Copenhagen, and it anchored a globe of relatives who shared holidays and funerals. Their service defined an era, while the family ties underscored how intertwined Europe’s thrones remained.

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother

George VI and Elizabeth Bowes Lyon were distant kin, counted as 13th cousins. In royal arithmetic that still qualified as inside the circle, though by practical standards it meant two families with ancient overlap. Their marriage steadied Britain through air raids, ration books, and careful optimism, proof that partnership could be both affectionate and dutiful. The genealogical footnote matters as context, showing how even a love match often touched the same long braid of ancestry.

King Henry VII and Elizabeth of York

Henry VII married his third cousin Elizabeth of York to end civil war and fuse rival claims. The union turned banners into a shared household, then produced heirs whose legitimacy exceeded any battlefield bargain. It brought Yorkists into Tudor service and calmed a noble class tired of wagers on succession. The cousin tie made acceptance easier for wary houses that valued blood as proof. A fragile crown became a dynasty, and the nursery did the work that armies could not.

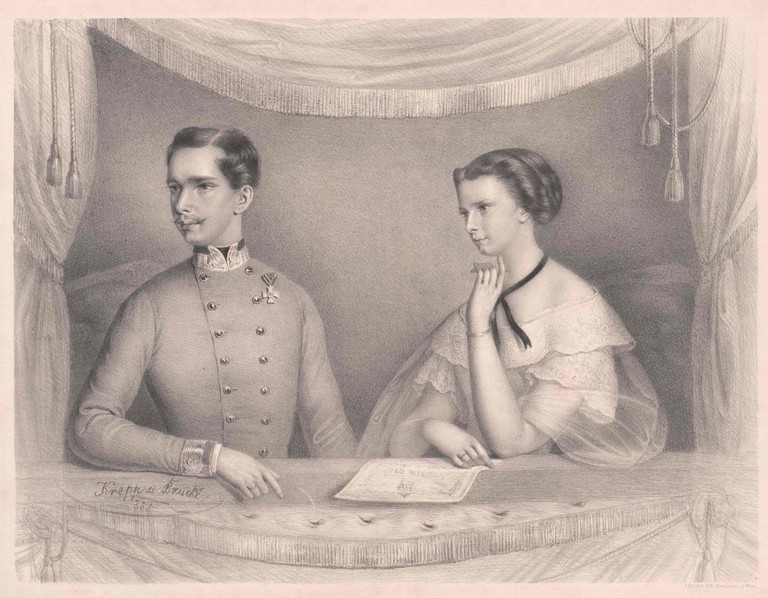

Emperor Franz Joseph I and Empress Elisabeth of Austria

Franz Joseph wed his first cousin Elisabeth of Bavaria, remembered as Sisi. The match kept influence within a familiar orbit while presenting charm to a restless empire. Court life pressed hard on Sisi, yet the alliance suited ministers who trusted kin over outsiders. The cousin union echoed a Habsburg pattern that prized internal solutions to external threats. It delivered continuity in ceremonies and councils, while later generations carried the biological cost of repeated closeness.

Francis II and Maria Theresa of Naples and Sicily

Francis II, last Holy Roman Emperor, married Maria Theresa of Naples and Sicily, his double first cousin. They shared the same set of grandparents, which concentrated inheritance and simplified diplomacy inside the family. The price sat in the nursery, where narrow pools risked fragile heirs. The marriage reflects a dynasty that treated weddings as constitutional tools, long before laboratories explained why variety matters. It solved short term politics and seeded long term vulnerabilities that history later tallied.