Much of labor’s progress came from quieter hands. These Black organizers stitched wages, safety, and dignity into daily work, then trained others to carry the fight into city halls and hiring halls. This gallery highlights builders who turned kitchens, buses, and shop floors into organizing schools. If their methods feel current, that is the point. Good tactics travel, and these leaders wrote playbooks still visible in action.

Rosina Corrothers Tucker

Rosina Corrothers Tucker organized the Ladies Auxiliary of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, turning family schedules into power. She taught record-keeping, ran kitchen meetings, and lobbied for fair hours that reached workers the law had skipped. Steady follow-up pushed agencies to enforce rules, not just announce them. One visit at a time, she grew dues, raised confidence, and helped win recognition that reshaped paychecks and respect across rail towns.

C. L. Dellums

C. L. Dellums built the Sleeping Car Porters from West Coast depots, then used that base to push fair employment laws that outlived any contract. He trained stewards to file clean cases, tracked patterns of bias, and carried those files into hearings where discrimination hid behind procedure. As a senior officer, he mentored younger organizers and linked unions with civil rights groups. Strategy, patience, and careful records turned late nights into policy that stayed.

E. D. Nixon

E. D. Nixon worked nights on Pullman runs and days linking unions with the NAACP and pastors. When Rosa Parks was arrested in 1955, he posted bail, called leaders, and helped launch the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Labor tools powered a citywide action: rapid mass meetings, printed leaflets, and carpools that kept people moving for more than a year. A simple, disciplined blueprint changed national law one ride at a time.

Maida Springer Kemp

Maida Springer Kemp moved from a garment line to training rooms across Africa and the Caribbean. She taught women to negotiate with confidence, built exchanges between unions, and argued that real wages require child care, apprenticeships, and portable skills. Her notebooks read like practical guides, full of exercises and sample agendas. By centering women’s leadership and trade skills, she made solidarity something measurable, teachable, and durable.

Dorothy Lee Bolden

Dorothy Lee Bolden recruited nannies and housekeepers between bus stops in Atlanta, building the National Domestic Workers Union in real time. She pressed for written wage agreements, Social Security contributions, and training that raised pay and pride. Schools and agencies became partners because she made standards easy to adopt. By putting rights into everyday conversations, she organized a sector many had written off and proved that domestic work is skilled work worthy of a contract.

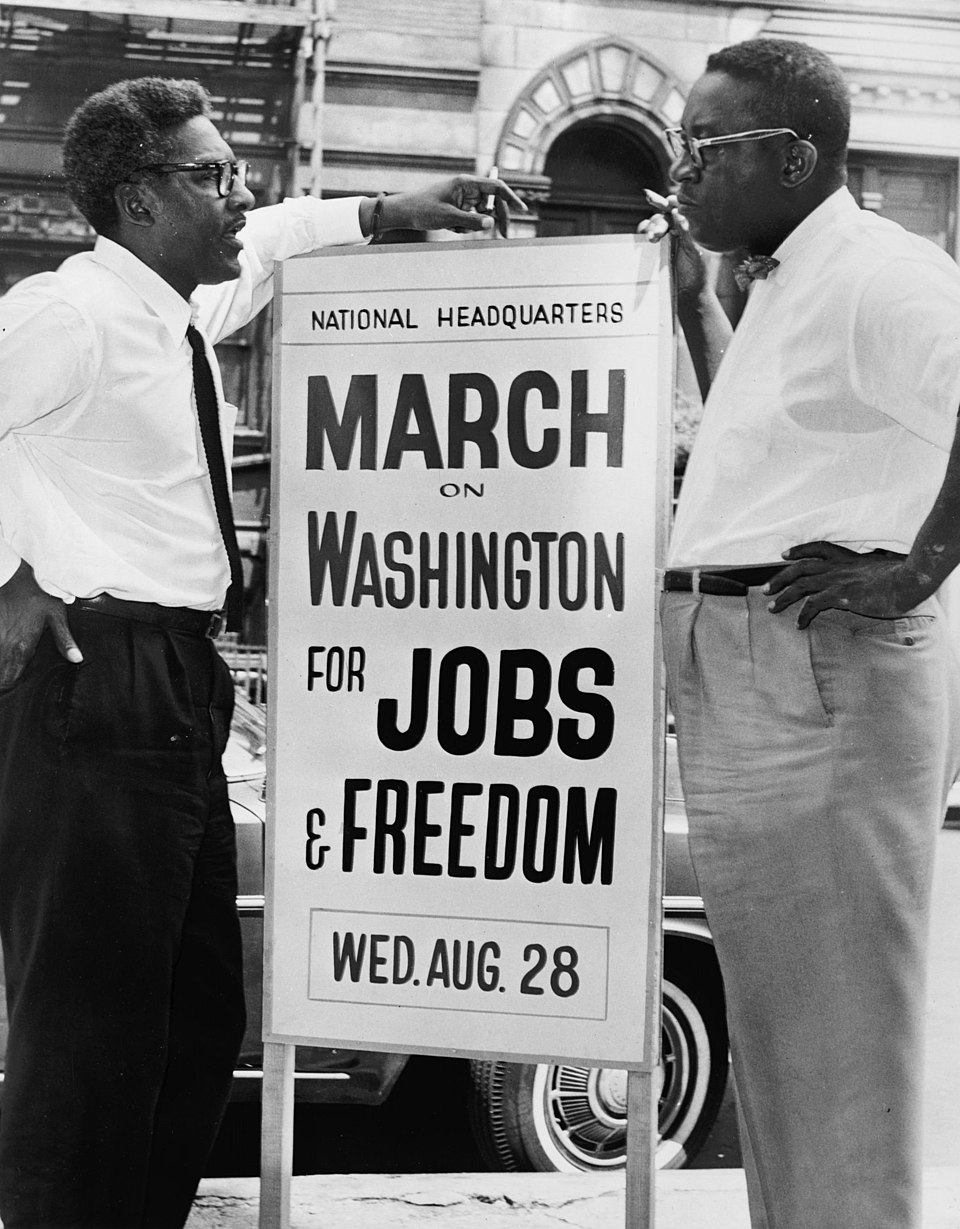

Cleveland Robinson

Cleveland Robinson, Jamaican-born and tireless, kept budgets sharp as secretary-treasurer of District 65 while planning logistics for the 1963 March on Washington. He pushed interracial organizing in retail and warehouses, built strike funds that could last, and helped found the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists. With clear messaging and careful numbers, he showed how a mid-sized local could move standards citywide and turn shop-floor fights into public policy.

Frank R. Crosswaith

Frank R. Crosswaith worked Harlem’s tenements and garment shops, building the Negro Labor Committee to connect Black workers with established unions. He ran forums, wrote plain-language guides, and pressed leaders to fight discrimination inside their own ranks as well as on the street. Treating education as organizing kept momentum between strikes and turned neighborhood clubs into pipelines for stewards and speakers able to hold a room and win a vote.