Peace often arrives quietly, carried by talks beside rivers or promises exchanged in crowded council houses. Across continents, Indigenous leaders worked for coexistence that protected land, language, and kin, even when pressure mounted from empires and settlers. Their diplomacy blended pragmatism with principle, creating space for ceremony, family, and trade to continue. Some agreements held for seasons, others for generations, yet each showed how patience and clarity can redirect history. These portraits honor voices that chose dialogue over spectacle and long horizons over short victories.

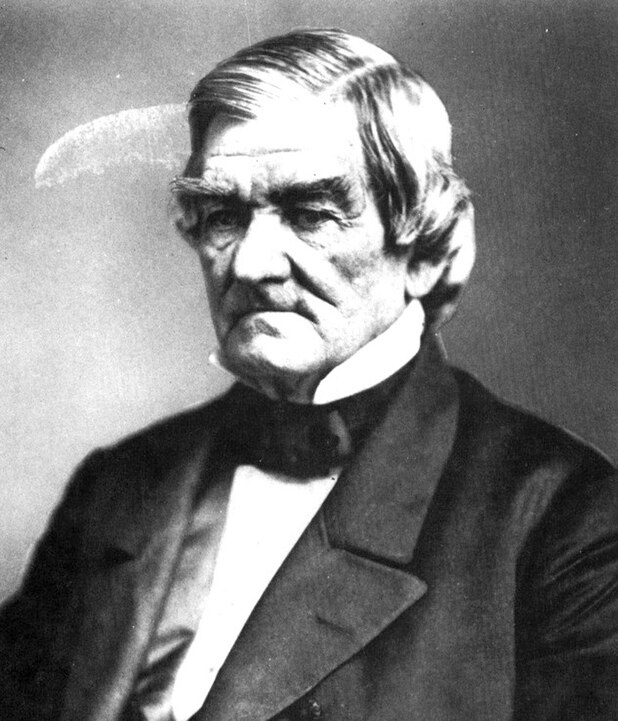

Massasoit Ousamequin (Wampanoag)

As sachem of the Wampanoag, Ousamequin, often called Massasoit, forged a 1621 mutual defense pact with Plymouth Colony. He sought stability after epidemic losses, trading food and knowledge for assurances that borders and sovereignty would be respected. The alliance tempered conflict for decades and allowed his people breathing room to rebuild. Though peace later frayed under new pressures, his early diplomacy showed how clear terms, shared rituals, and careful reciprocity could hold wary neighbors in balance.

Tamanend (Lenape)

Lenape chief Tamanend became a symbol of good faith through agreements with William Penn in the 1680s. Negotiations emphasized fair purchase, wampum protocols, and public ceremony, which anchored expectations beyond a single meeting. While later policies broke that spirit, Tamanend’s approach modeled coexistence grounded in consent, not coercion. His legacy endures in stories and place names that recall a moment when careful words and visible respect kept trade open and tempers low along the Delaware River.

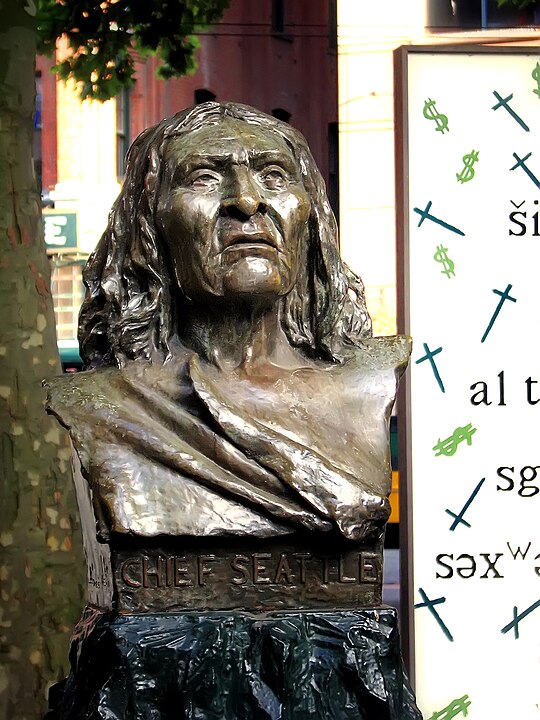

Chief Seattle Si’ahl (Duwamish, Suquamish)

Si’ahl, known as Chief Seattle of the Duwamish and Suquamish, navigated treaty talks in 1854 to 1855 while urging calm between villages and incoming settlers. He advocated for protections of fishing sites, burial grounds, and the right to remain near ancestral waters. Though translations and power imbalances complicated outcomes, his diplomacy sought a future where commerce, worship, and kinship could continue side by side. The city that bears his name reflects both possibility and the obligations his people still press to honor.

Manuelito (Navajo Nation)

After the Long Walk and imprisonment at Bosque Redondo, Diné leader Manuelito pressed the United States for return to Navajo homelands. In 1868 he helped secure a treaty that ended confinement, restored a portion of the land base, and affirmed the right to education on Navajo terms. His stance combined resistance to raids with practical negotiation, insisting that peace required soil, water, and herds. By prioritizing home over exile, he set a template for survival rooted in place rather than dispersal.

Crowfoot (Siksika, Blackfoot Confederacy)

Siksika chief Crowfoot faced collapsing bison herds and mounting settler pressure on the northern plains. He chose treaty in 1877, seeking food security, medical aid, and protection for his people under Treaty 7. His speeches urged restraint to avoid cycles of reprisal that would destroy communities already strained by disease and scarcity. Though implementation fell short, Crowfoot’s leadership aimed to secure time, rations, and schooling while preserving dignity, ceremony, and the right to decide local matters.

John Ross (Cherokee Nation)

Cherokee Principal Chief John Ross pursued law and diplomacy to defend sovereignty as removal pressures mounted in the 1830s. He led constitutional reform, petitioned Congress, and supported the Worcester v. Georgia case that affirmed Cherokee self rule. Even after the Treaty of New Echota was signed by a minority faction, Ross organized aid and tried to limit suffering on the Trail of Tears. His career shows persistence for coexistence through courts, councils, and careful record keeping when arms would only deepen loss.

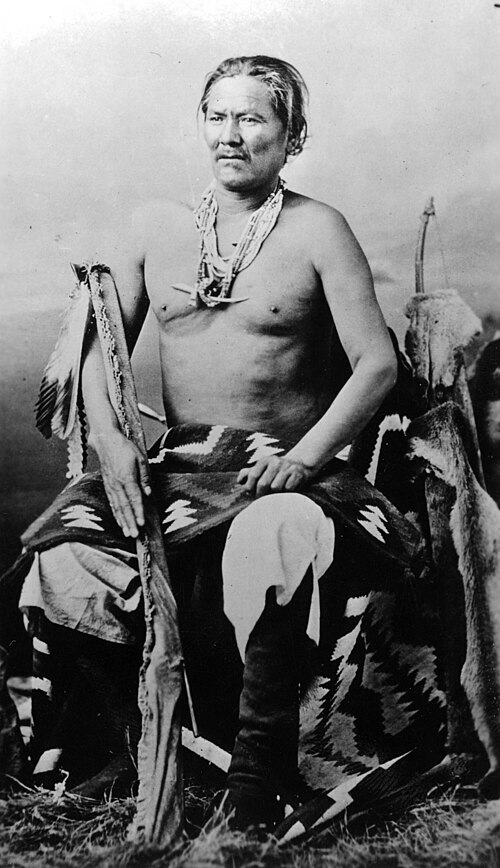

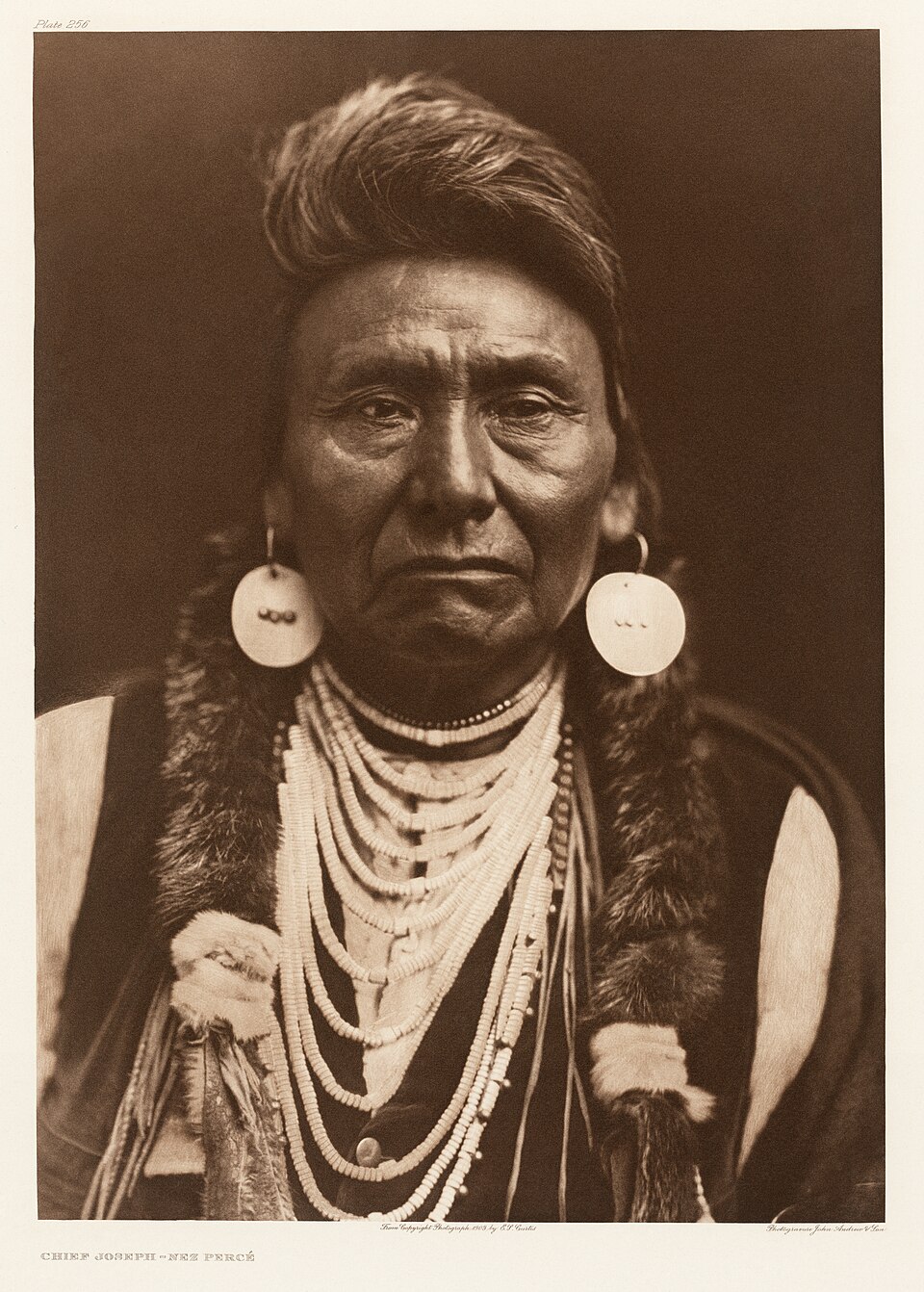

Chief Joseph Hinmatóowyalahtq’it (Nez Perce)

Hinmatóowyalahtq’it, known as Chief Joseph of the Nimiipuu, argued that treaties should be honored and that his people be allowed to remain in the Wallowa Valley. When war came in 1877, he led a disciplined retreat that spared civilians whenever possible and pressed for safe passage to Canada. His eventual surrender paired grief with an appeal for humane terms. In speeches and petitions that followed, he advocated for a lawful peace grounded in truthful promises and the right to return home.

Bennelong Woollarawarre (Eora)

Woollarawarre Bennelong of the Eora acted as a bridge with Governor Arthur Phillip in late 18th century Sydney. He learned English, visited London, and pressed for protocols that could reduce violence around fishing grounds and sacred sites. Mediation strained under frontier expansion, yet his role recorded names, places, and practices that authorities could not ignore. By insisting on ceremony and dialogue, he carved small corridors of respect that offered glimpses of coexistence amid rapid and often brutal change.

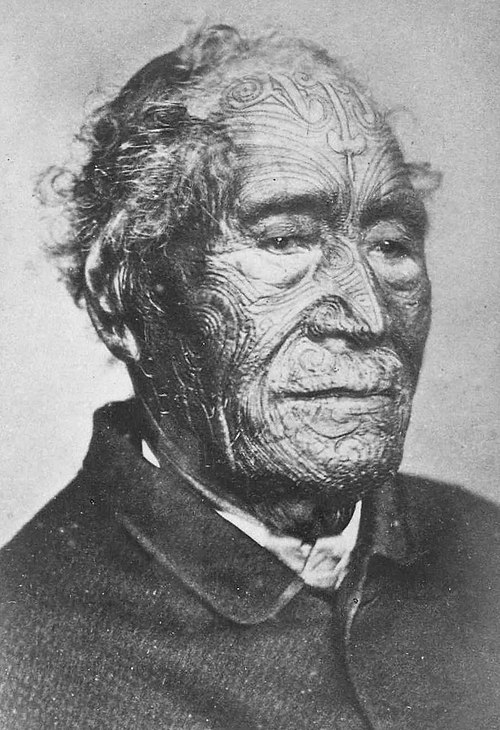

Tamati Waka Nene (Ngāpuhi, Aotearoa New Zealand)

Ngāpuhi rangatira Tamati Waka Nene supported the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 and later argued that Māori and the Crown must honor its terms in practice. He urged restraint during conflicts in the 1840s, believing trade and stability would protect communities better than prolonged war. His counsel emphasized reciprocity and the authority of chiefs alongside introduced law. By championing dialogue across language and custom, he helped keep channels open when mistranslation and mistrust threatened to close them.

Te Whiti o Rongomai (Parihaka, Taranaki)

Te Whiti o Rongomai of Parihaka led nonviolent resistance to land confiscations in Taranaki. He welcomed displaced families, planted on seized fields, and met soldiers with songs, food, and ploughs instead of weapons. The 1881 invasion shattered the community, yet his message insisted that justice and peace could not be separated. His example influenced later movements, showing how steadfast calm, moral clarity, and organized care can restrain violence and keep a future open for dialogue.

Moshoeshoe I (Basotho Kingdom)

Moshoeshoe I unified Basotho communities in the 19th century highlands, using diplomacy to buffer pressures from Boer republics and British authorities. He granted refuge to neighbors, negotiated boundaries, and leveraged missionary correspondents to carry messages beyond the mountains. When war threatened, he sought protectorate status to preserve autonomy and land. His state survived because negotiation stood alongside defense, proving that careful alliances, shared grazing, and respect for asylum could hold a diverse people together.