Bad choices can snowball. One order, vote, or risky call can ripple across years, borders, and bank accounts. This guide spotlights 10 decisions with dates, places, and results you can verify. You will see wars launched in 1812 and 2003, bans passed in 1920, and go signals given on icy mornings in 1986. The lesson is practical. Ask for better data, test the plan, and slow down when stakes are high. Clear checklists, honest timelines, and brave “stop” calls save lives and money.

1. Napoleon Invades Russia, 1812

In June 1812, Napoleon crossed the Niemen River with the Grande Armée, about 600,000 troops. He expected a short campaign. Russian forces used scorched earth tactics, burning supplies and pulling back. By September, the army reached Moscow, which then burned. Winter hit hard. Starvation, disease, and frost hammered columns on the retreat across the Berezina in November 1812. Fewer than 100,000 men returned. The empire’s aura cracked. Basic rule, distance, weather, and logistics in miles, days, and calories beat confidence every time.

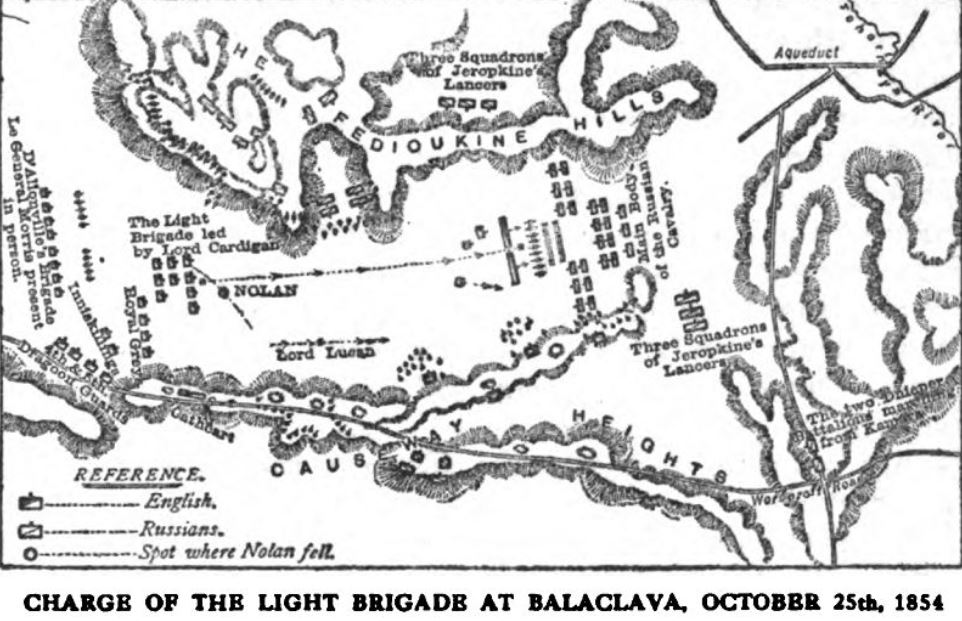

2. The Charge of the Light Brigade, 1854

On 25 October 1854 at Balaclava in Crimea, a garbled order sent the British Light Brigade straight into Russian guns. The ride down the North Valley exposed cavalry to artillery on three sides. In about 7 minutes, roughly 110 of 670 troopers died, with hundreds wounded or missing. Confused command chains and vague maps set up the disaster. Lesson, write orders with exact targets and bearings, then confirm by messenger. Clear coordinates and repeat-backs prevent brave people from dying on avoidable errands.

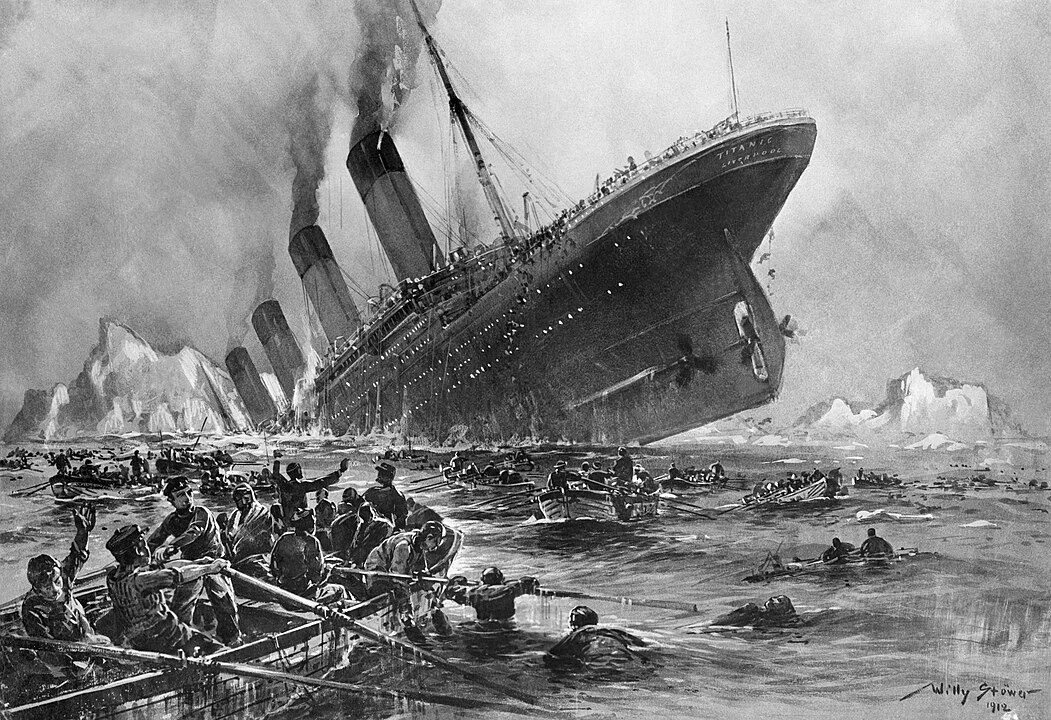

3. The Titanic’s Speed in Ice, 1912

RMS Titanic struck an iceberg at 11:40 p.m. on 14 April 1912, then sank at 2:20 a.m. Lifeboat capacity covered about half the people aboard. Despite ice warnings, the ship kept near 22 knots on a moonless night south of Newfoundland. Steel plates and brittle rivets failed as compartments flooded. More than 1,500 lives were lost. After hearings in 1912, rules required enough boats for all and 24 hour radio. Today’s takeaway, slow down when sensors and reports disagree, and plan redundant exits.

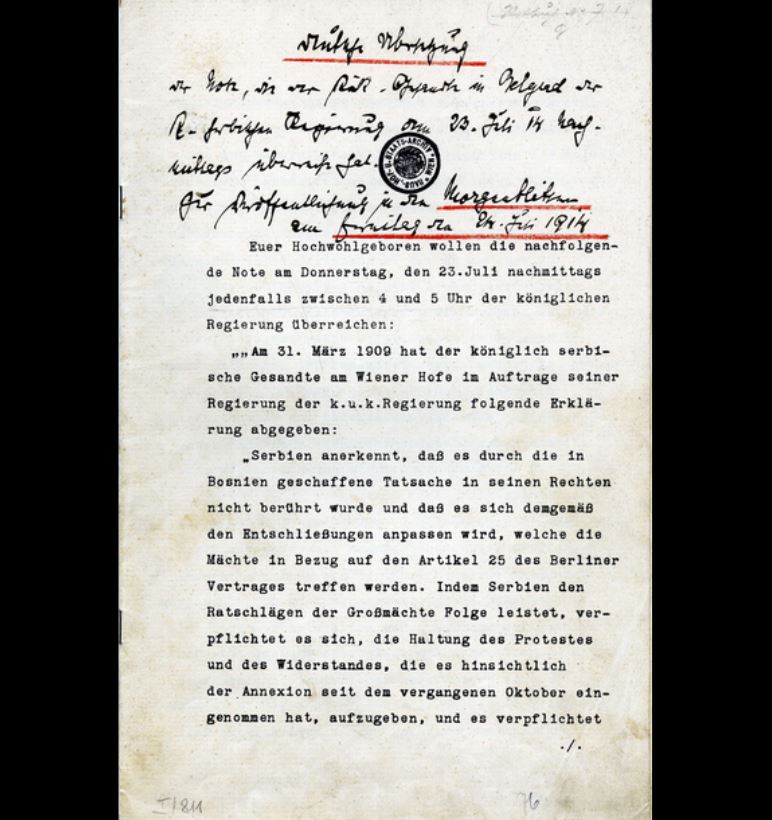

4. Austria-Hungary’s Ultimatum to Serbia, 1914

After the 28 June 1914 Sarajevo assassination, Vienna issued a hard ultimatum on 23 July with terms designed to be refused. Alliances then snapped into place. Russia mobilized, Germany backed Austria-Hungary, and by early August Europe slid into World War I. By 1918, the conflict killed millions and redrew borders. The fateful decision was betting a local crisis would stay small. Better path, build cooling periods in days and use neutral investigators. Timers and third parties reduce chain reactions between armed allies.

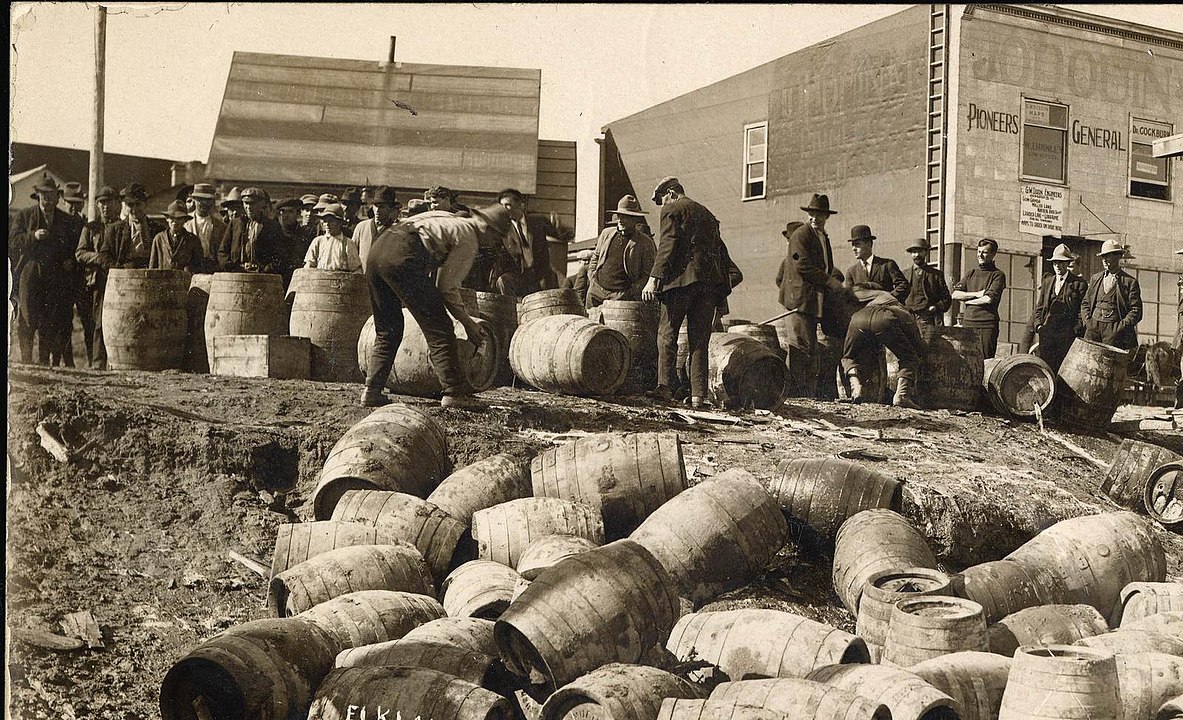

5. Prohibition in the United States, 1920

The 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act took effect on 17 January 1920, banning the sale of alcohol. Illegal markets surged. Organized crime grew in cities like Chicago by the mid 1920s. Tax revenue vanished, enforcement costs rose, and poisonings spiked from unsafe liquor. Public support eroded. The 21st Amendment repealed Prohibition in December 1933. Policy lesson, bans without realistic enforcement or public buy-in can fail fast. Pilot programs, health data, and phased rules work better than sweeping national prohibitions.

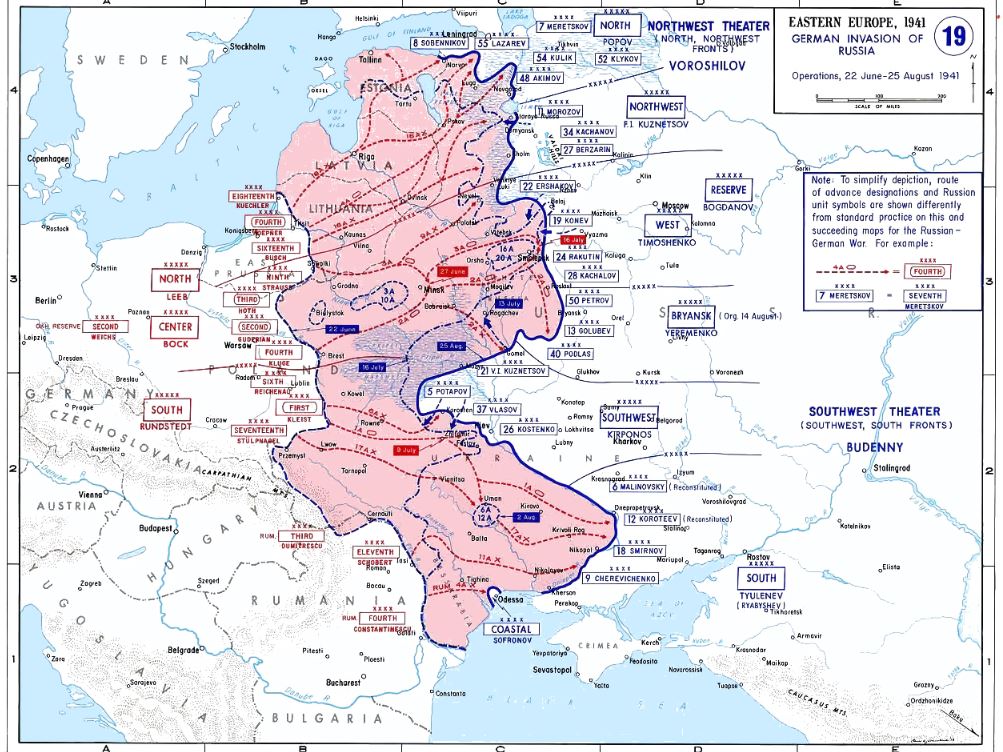

6. Hitler Invades the Soviet Union, 1941

Operation Barbarossa began on 22 June 1941 with three army groups driving toward Leningrad, Moscow, and Kyiv. Early gains could not overcome vast distances, supply gaps, and winter. The Moscow counteroffensive in December 1941 showed the plan had broken. By 1943 at Stalingrad and Kursk, the Wehrmacht was in retreat. Casualties reached millions. The decision to open a second front while Britain still fought proved fatal. Strategy note, do not split strength against a larger foe across thousands of miles and two winters.

7. The Bay of Pigs Invasion, 1961

On 17 April 1961, a CIA-backed force landed at Playa Girón in Cuba. Air support was limited, local resistance was stronger than expected, and logistics faltered. Within three days, the invasion collapsed. The episode damaged U.S. credibility and pushed Havana closer to Moscow, setting the stage for the 1962 missile crisis. Planning gaps included ignored warnings and poor risk calendars. Core fix, stress-test assumptions with red teams and cutoffs. If key conditions fail before H hour, cancel rather than escalate a weak plan.

8. Chernobyl Safety Test, 1986

On 26 April 1986 near Pripyat, a late-night turbine rundown test at Reactor No. 4 was run with disabled safeguards and low power, creating unstable conditions. A power surge caused explosions and fire, releasing radiation across Europe. Evacuation followed within 36 hours. The disaster drove major reactor design changes, emergency drills, and an international safety culture. Lab rule, never bypass interlocks for schedule pressure. If a test drifts outside safe ranges, stop, reset, and reschedule with full oversight and written sign-offs.

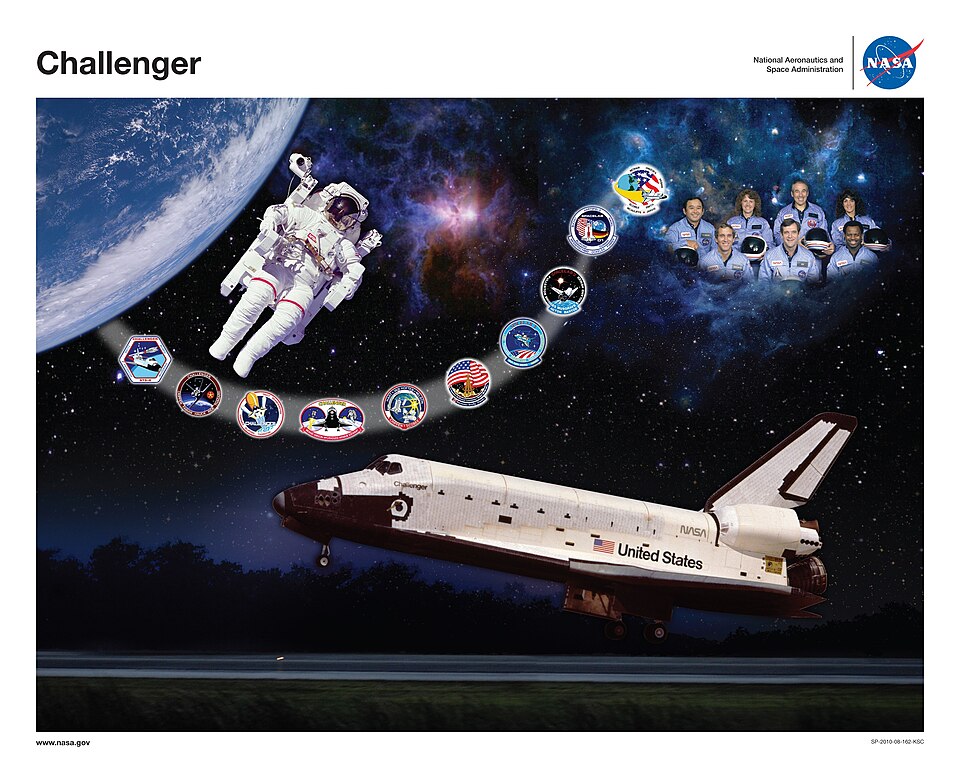

9. Challenger Launch Decision, 1986

On 28 January 1986 at Cape Canaveral, Space Shuttle Challenger launched in freezing weather. Engineers warned about O-ring performance below 53°F. Ice covered the pad that morning. At 73 seconds, a joint failed, leading to breakup and the loss of seven crew. The Rogers Commission later traced flaws in communication and risk acceptance. Practical lesson, weather minimums and component limits in degrees and minutes are hard lines. Safety teams need authority to veto, and concerns must reach the final go, no-go call.

10. The 2003 Iraq Invasion

On 20 March 2003, a coalition invaded Iraq based on intelligence that later proved wrong about active weapons programs. Baghdad fell in April, but the postwar plan stumbled. Disbanding the army and de-Ba’athification in May 2003 fueled insurgency. Years of conflict followed, costing lives and billions of dollars. Planning lesson, pressure-test sources, game out months after victory, and define exit metrics in clear numbers. War decisions must include the day 100 and day 1,000 plan, not only day one.