During the Cold War, immigration raids grew fast, large, and highly visible. In 1954, federal sweeps moved so quickly that families awoke to buses at dawn and empty seats by night. Officials said the goal was border control and jobs protection. Critics warned of profiling and rushed decisions. Records from the 1950s show huge apprehension totals, but many counted repeat crossings. Understanding how it happened helps teens see how numbers, laws, and fear shaped real lives in that tense era.

1. Operation Wetback, 1954

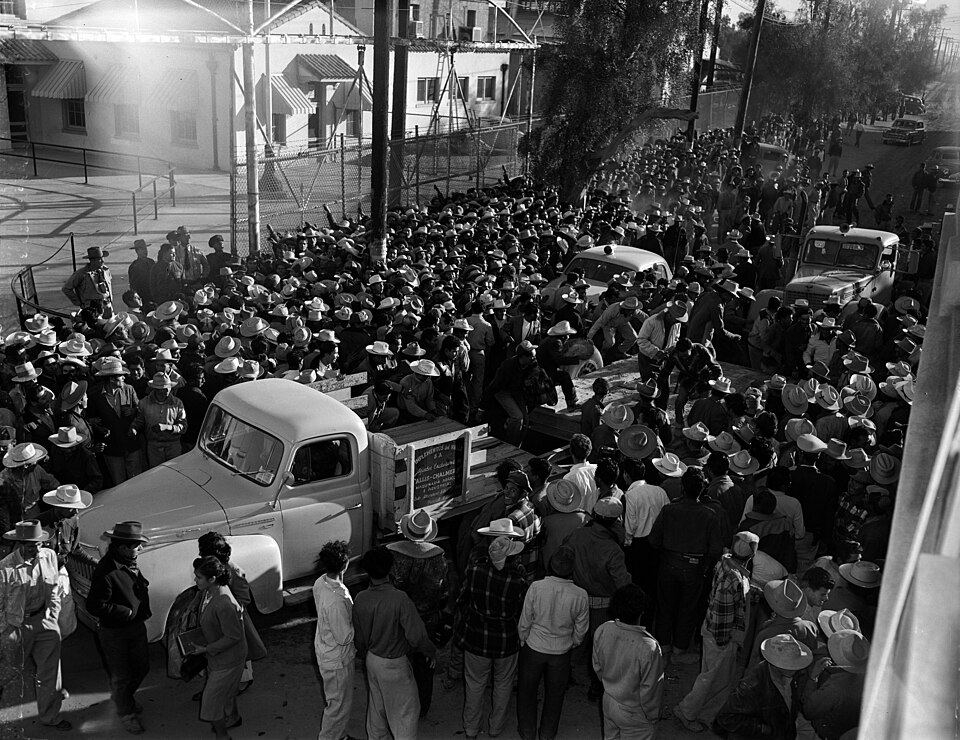

In summer 1954, the Immigration and Naturalization Service launched Operation Wetback across California, Arizona, and Texas. Border Patrol agents, local police, and highway officers conducted roadside checks, factory raids, and farm sweeps. By August, officials reported hundreds of thousands of apprehensions. Many people were processed the same day and sent to the border. The stated aim was to stop unauthorized hiring and reduce chaotic crossings that had risen in the early 1950s after wartime labor needs faded.

2. How It Moved So Fast

Speed came from coordination. Agents set roadblocks on routes into Los Angeles, San Diego, El Paso, and the Rio Grande Valley. Buses and trains carried people to border stations within hours. Boats also moved groups to Mexican ports like Veracruz to make quick reentry harder. The system emphasized short interviews, rapid decisions, and group transport. That pace created mistakes, with some long term residents swept up because they lacked papers on them during surprise checks.

3. Laws That Enabled It

Two federal frameworks powered removals. The 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act consolidated earlier laws, expanded grounds for deportation, and eased cooperation with local police. Public Law 78 extended the Bracero farm labor program, which complicated enforcement by mixing recruited workers with returning families. Together, these rules let agents sort people quickly at the border or a station. Speed reduced review time, so appeals were rare, especially for Spanish speaking farmworkers far from legal help.

4. Who Was Targeted

Most people caught were Mexican nationals, but raids also pulled in Mexican Americans who were citizens. Workplace checks in Los Angeles and agricultural sweeps near Fresno, Yuma, and McAllen relied on quick questions about birthplace, papers, and employer. Some lawful residents were held until family produced documents. Teens should know status can be complex. In the 1950s, record keeping was weaker, and many families moved with seasonal crops, which made proof harder.

5. What The Numbers Mean

Government tallies listed roughly one million apprehensions in 1954, often quoted as 1,074,000. That does not equal one million unique people. Many were counted again after trying to return, and a large share accepted voluntary departure rather than formal deportation. Even with overlaps, the scale was massive for one year. The point is to read numbers carefully. They show pressure at the border, but also the limits of counting complex human movement.

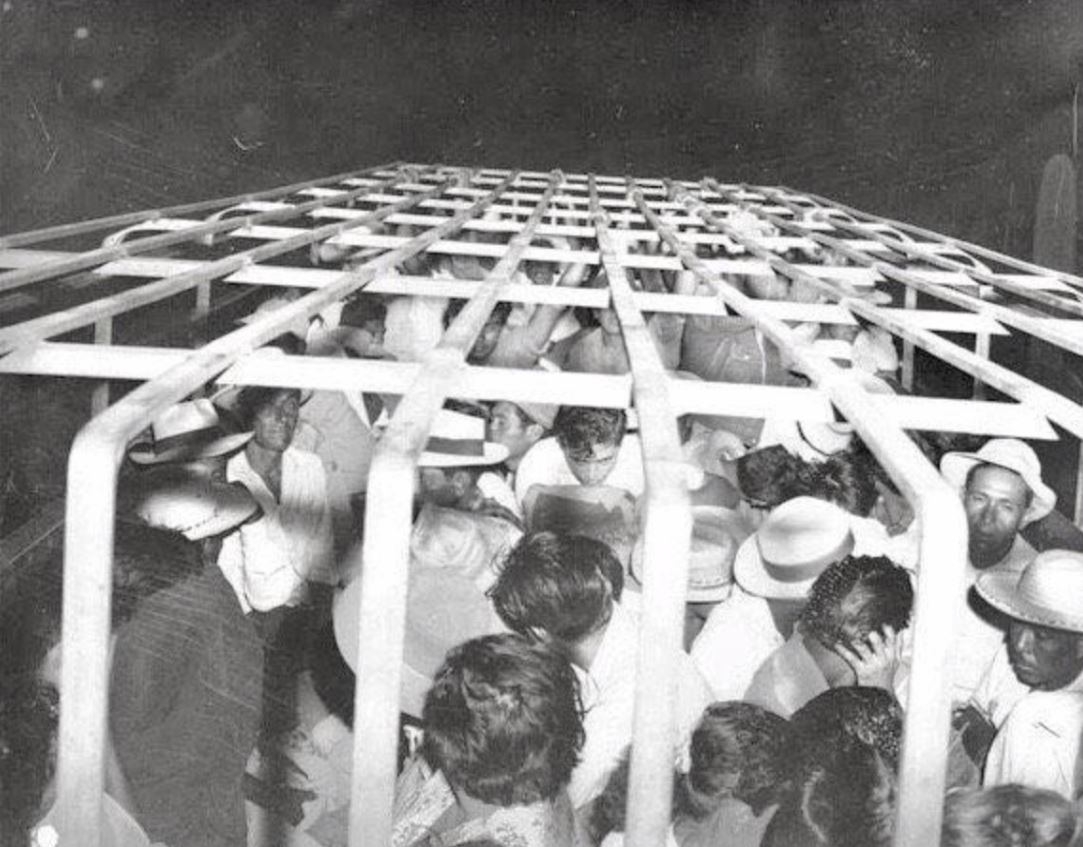

6. Conditions And Criticism

Heat, crowding, and rushed transport drew complaints. Reports told of people riding hours without water, or being left far from home cities across the border. Civil rights groups questioned due process, and some clergy urged more humane steps like timed departures to reunite families. Safety note for students researching: use reliable archives and official yearbooks, since headlines from the era sometimes mixed rumors with facts during tense summer raids.

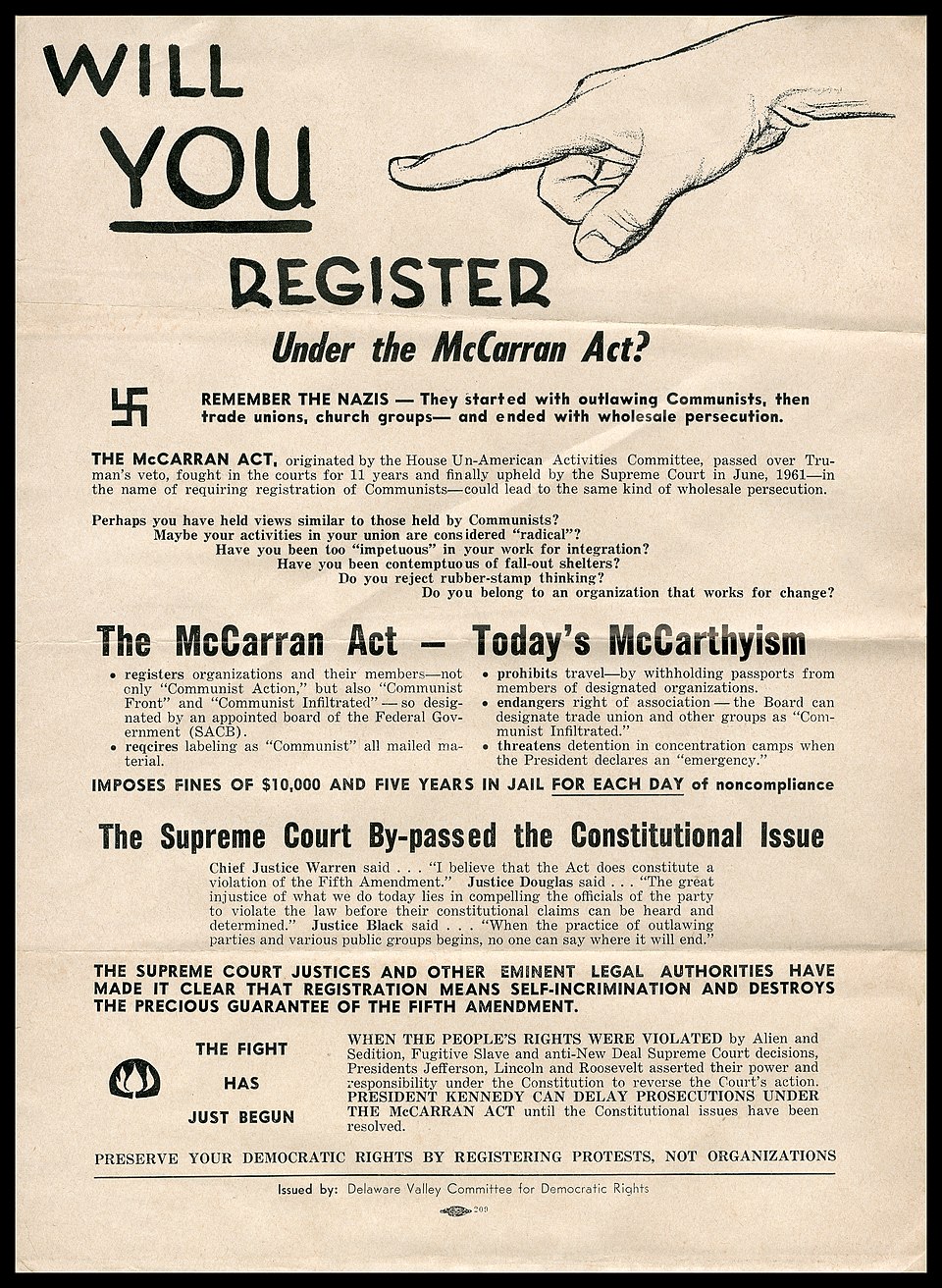

7. The Cold War Climate

Anti communist fears shaped policy across the 1950s. The 1950 Internal Security Act and loyalty programs made officials wary of perceived threats. Immigration agents also removed some noncitizens labeled subversive, often on political grounds rather than crimes. While that track was smaller than border sweeps, the message was clear. In a Cold War mindset, fast action seemed safer than slow review, even when it strained rights that courts later strengthened.

8. Aftermath And Change

Apprehensions dropped in late 1954 as large sweeps eased. The Bracero program continued until 1964, then ended as Congress revised immigration in 1965. Over time, courts expanded access to counsel and hearings, especially for long term residents. Yet the basic tensions stayed. Employers still needed labor, families still moved for work, and border operations still cycled with politics. The lesson for teens is to ask who benefits, who is harmed, and how numbers are counted.