On a quiet street in Rancho Santa Fe, California, deputies entered a rented mansion in late March 1997 and found 39 people dead. The case quickly became known by the group’s name, Heaven’s Gate, and the leader at the center of it all, Marshall Applewhite. For teens trying to understand how a single person could lead dozens toward such a devastating choice, the real story is about charisma, isolation, and a belief system that tightened over time until it felt unbreakable.

This overview focuses on who Applewhite was, how the group formed, why 1997 became the tipping point, and what experts say are the red flags of high-control groups. The details below come from official records and respected histories, not rumor or hype.

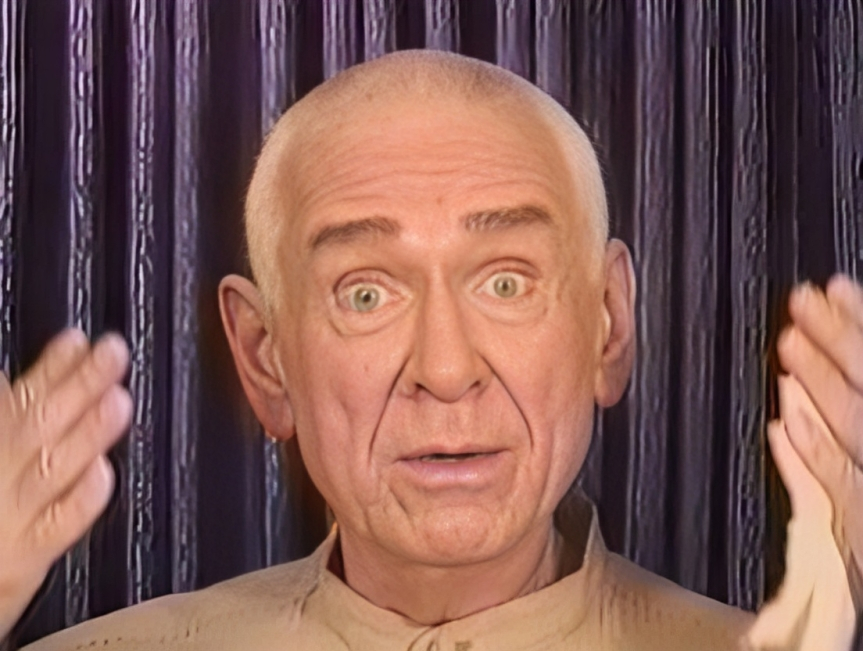

Who he was before the headlines

Marshall Herff Applewhite was a Texas-born music teacher who drifted after career setbacks and personal crises. In the early 1970s he met Bonnie Nettles, a nurse whose spiritual interests ranged from Bible study to New Age ideas. Together, they became convinced they had a mission: to guide a small group of seekers to a higher level of existence they called the Next Level. Encyclopaedia Britannica summarizes this early period clearly, including the claim that the pair saw themselves as figures foreshadowed in scripture.

Applewhite and Nettles began touring community rooms and small halls in 1975. Flyers promised answers about life after death and a path beyond human limits. People who felt stuck or searching found the message compelling. Some left jobs and families to join. The group tried different names, then settled on Heaven’s Gate. Inside, Applewhite used the nickname “Do” and Nettles used “Ti.”

The turning point with Nettles

Nettles died of cancer in 1985. That loss forced a change in the group’s theology. If the trusted co-leader could die, then the body might be only a temporary “vehicle” that a believer could shed before reaching the Next Level. Scholars who study new religious movements note that shifts like this, after a founder dies, often make groups more insular. Applewhite now taught alone, and the rules grew stricter.

How the group evolved in the 1990s

By the early 1990s, Heaven’s Gate lived communally, kept a tight daily schedule, and expected members to give up many normal ties. The group ran a small web-design business under the name Higher Source, which supported their closed-door lifestyle. Recruiting slowed, but the core stayed devoted.

Outside events then gave Applewhite fresh fuel. In 1995 astronomers announced Comet Hale-Bopp. As it brightened in 1997, Applewhite framed it as a sign that the Next Level was opening a window. NASA’s science updates from that spring show just how bright and long-visible Hale-Bopp became, which helps explain why it dominated the night sky and the news. The comet itself was not mystical. For Applewhite, it was useful symbolism he tied to his group’s story.

According to official summaries from San Diego County authorities and careful histories, Applewhite recorded farewell messages with his followers in March 1997 and spoke about leaving Earth for the Next Level. The mansion in Rancho Santa Fe had been rented the previous fall. The community around the house knew little about what was happening inside.

March 1997, step by step

On March 26, 1997, an anonymous call led deputies to the house. What they found became the largest mass suicide on U.S. soil, confirmed by the San Diego County Sheriff’s Office. The people inside had prepared in groups over several days. Notes and videos indicated they saw death as a transition, not an end. The county medical examiner later reported that toxicology and autopsy findings supported a coordinated plan that relied on depressant drugs and suffocation, rather than any outside attack.

Numbers matter here, because they cut through myths. All 39 dead were members of Heaven’s Gate, including Applewhite. The victims were adults, men and women, and there were no signs of a struggle. Local and national outlets recorded the basics the same way at the time, and those key details have stayed consistent in later reviews.

It is easy to focus on the public oddities that showed up in headlines, like matching outfits or references to science fiction. It is more important to see the pattern underneath. Over two decades, the group’s beliefs grew tighter, daily life grew more controlled, and criticism from outsiders was steadily shut out. When Applewhite reframed death as a required step to reach the Next Level, long-time members were already conditioned to follow him.

How experts explain recruitment and control

Scholars who study high-control groups say there is no single “type” of person who gets pulled in. What matters is timing, need, and method. Applewhite offered certainty to people who felt uncertain. He gave them a schedule, a language, and a community that praised sacrifice. Over time, that community replaced outside feedback. When the only voices you hear are inside the room, extreme ideas can start to sound normal.

You can spot common tactics across different groups and decades. Leaders set up special terms that only insiders use. They promise a clean break from a messy world. They isolate members from family contact. They claim unique insight into cosmic events, then give followers urgent tasks to prove loyalty. None of these moves look dangerous on day one. Together, practiced daily, they add up to a powerful hold.

If you are a teen reading about 1997 and wondering what to do with it, the answer is not fear. It is awareness. Learning how influence works helps you keep your own steering wheel. It also helps you support friends who might be pulled toward groups that demand total obedience or secrecy.

What the 1997 case still teaches

First, history matters. The Heaven’s Gate tragedy did not come out of nowhere. It traces back to a pair of founders in the 1970s, a leadership shift in 1985 when Nettles died, and a final push built around a comet bright enough to catch anyone’s eye in 1997. Official timelines and reputable histories match on those milestones.

Second, language matters. Applewhite used phrases like “Next Level” and “vehicle” to make extreme choices sound technical, almost clinical. When big life decisions get renamed to remove the human cost, pause. Ask what the plain-English version would say.

Third, outside feedback matters. People in tightly controlled spaces lose mirrors from the rest of the world. Healthy groups can handle questions and visits. Unhealthy groups label questions as betrayal, then cut ties. That boundary, more than any single doctrine, is a useful early test.

Finally, empathy matters. The people who died were not jokes. They were adults who wanted meaning and thought they had found it. Remembering them with care honors the larger point of learning from the past.

Sources

- San Diego County Sheriff’s Office, Heaven’s Gate case overview. Confirms 39 deaths, multi-day timeline, and largest U.S. mass suicide status. Sept 2025. sdsheriff.gov

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, entries on Marshall Applewhite and Heaven’s Gate. Founders’ background, early recruiting, and belief system. Sept 2025. Encyclopedia Britannica+1

- NASA JPL, Hale-Bopp observing campaign release, March 1997. Brightness and visibility context for the comet. NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- Associated Press, “Today in History: March 26”. Date and basic summary of the Rancho Santa Fe discovery. Aug 2024. AP News

- Los Angeles Times, April 12, 1997. Medical examiner confirms cause and manner findings from autopsies. latimes.com