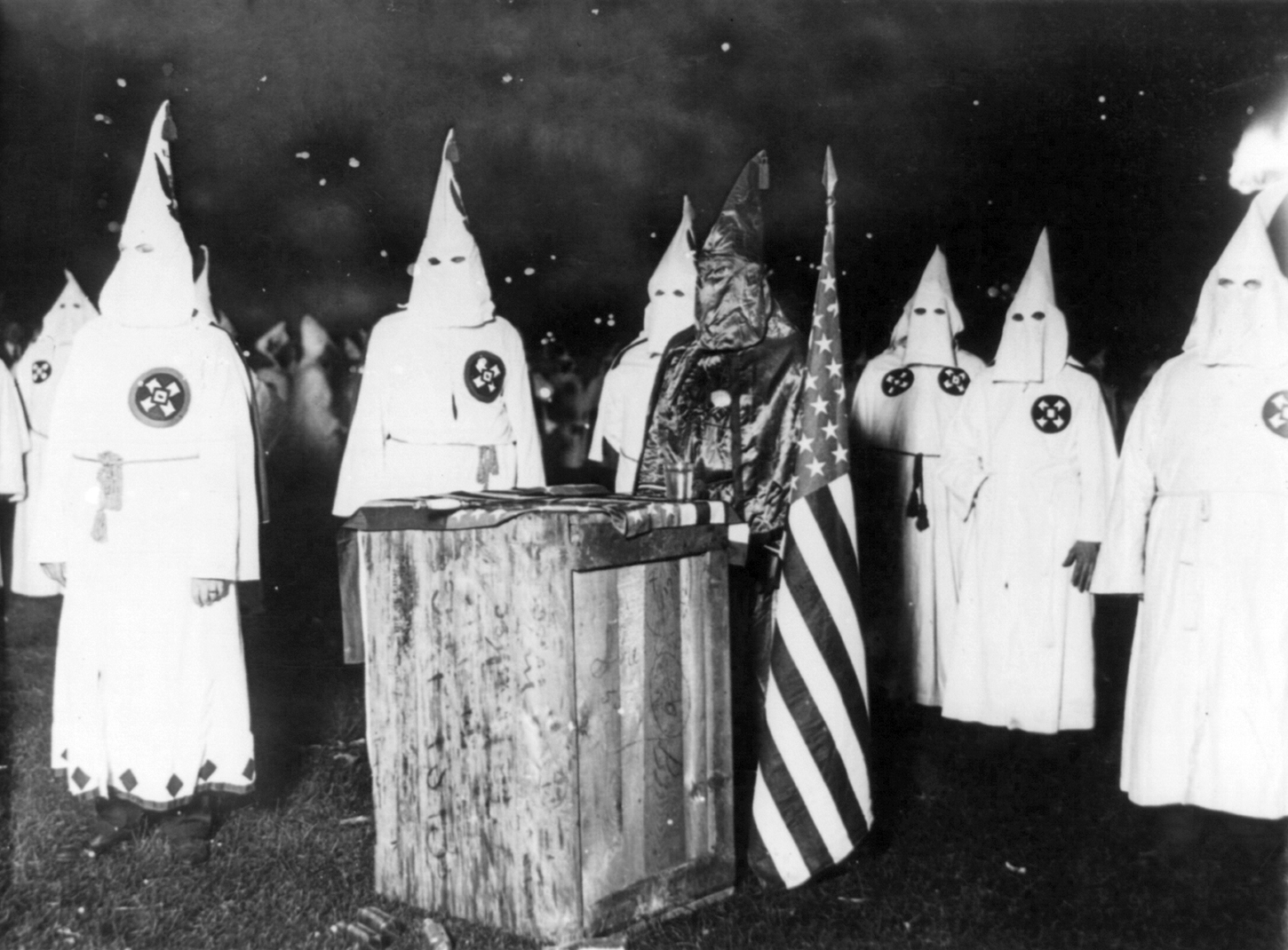

The image most people know is the burning cross and the hood. What this really means is terror made public, violence turned into ritual, and a message sent to anyone who dared claim equal rights. The Ku Klux Klan was not a passing fever dream or a pack of cranks hiding in barns. It was a movement that recruited widely, learned to fund itself, infiltrated politics, and adapted to changing times. Its power grew because far too many people treated it as normal.

Here’s the thing: the Klan rose in moments of upheaval by promising to restore an imagined order. It found allies in pulpits and courthouses, gained cover from silence, and fed on fear of change. When federal force and the courts squeezed it, the Klan morphed. When the culture made room for euphemisms, it rebranded. The story is not just about a hate group. It’s a ledger of how institutions either shut the door on organized terror or held it open.

Origins in the Ruins of War

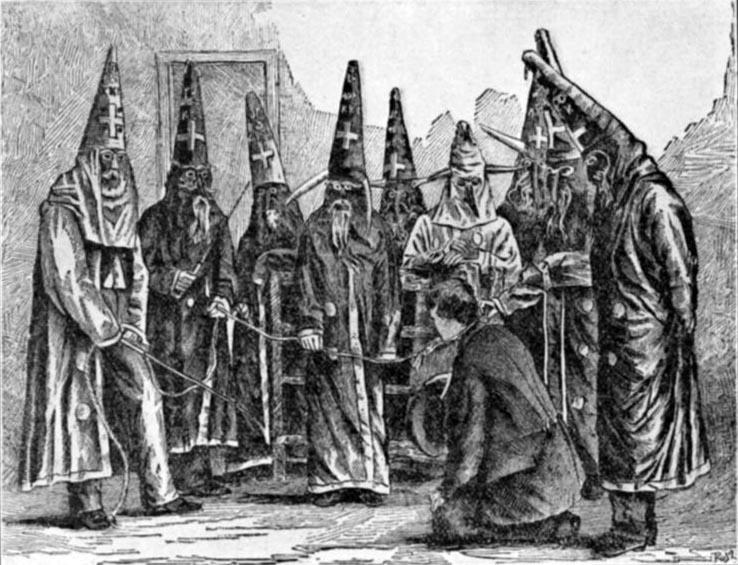

The first Klan began in late 1865 in Pulaski, Tennessee, formed by ex-Confederate officers who turned a private fraternity into a tool of racial control. The Civil War had ended, slavery was abolished, and Black Americans were voting, holding office, and claiming public space. For men who saw equality as defeat, a secret order offered a way to reassert dominance away from the battlefield but with the same intent.

Early disguises were chaotic, not the uniform white hoods later made famous. Riders wore animal masks, ragged costumes, and carnival pieces to appear ghostly and unearthly in rural nightscapes. The masquerade gave cover, but the purpose was precise. The aim was to break Reconstruction by terrorizing freedpeople and any white Southerners, teachers, ministers, and officials who supported their rights.

From Fraternity to Terror Campaign

Night rides escalated quickly into a system. Homes were invaded. Schools and churches were burned. People were dragged from beds and tortured to extract oaths of submission. Violence was not random; it targeted voting sites, officeholders, and organizers to make citizenship too costly to attempt.

Sheriffs, judges, and local elites often looked away or joined in. When law enforcers are the masked men, reporting a crime becomes an act of peril with no remedy at the end of it. That collusion multiplied the Klan’s reach beyond its headcount, since a single threat backed by a courthouse can empty a town square.

Federal power finally moved. Between 1870 and 1871, Enforcement Acts authorized the president to use troops and suspend habeas corpus to crush Klan cells, and federal prosecutions followed. The first Klan buckled under this pressure, only to see successor groups like the White League and the Red Shirts take up the project of suppressing Black voting with open daylight violence.

The lesson stuck: when Washington enforced rights, the Klan retreated. When it didn’t, the movement filled the vacuum.

A Movie Writes a Myth, and a Revival Follows

In 1915, a blockbuster film rewrote the first Klan as chivalric guardians and turned terror into pageantry for Northern audiences. Myth moved policy. Screenings reached the White House, and the movie’s iconography became a recruitment brochure disguised as entertainment. At Stone Mountain, Georgia, a new Klan lit a cross and proclaimed itself heir to the old cause.

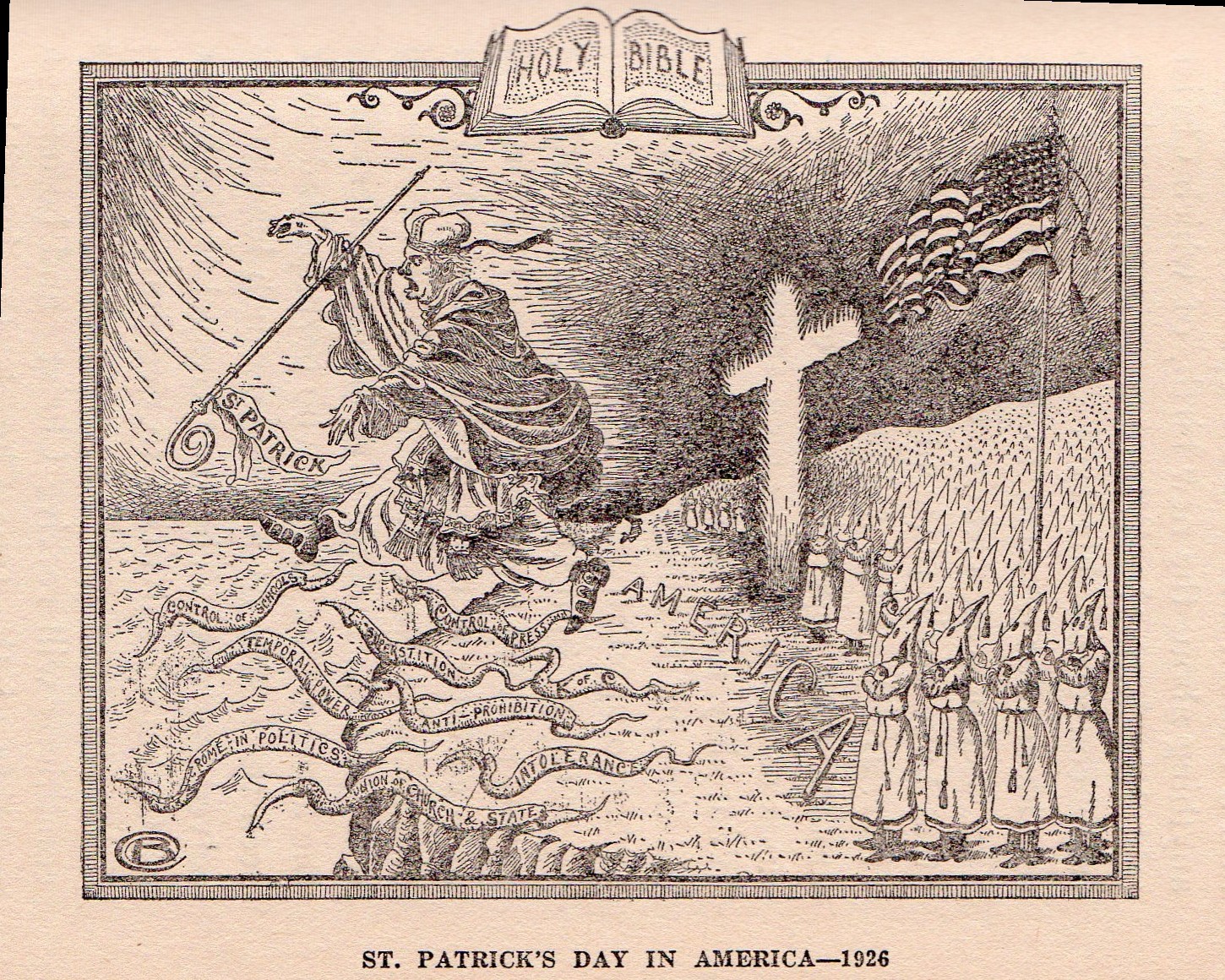

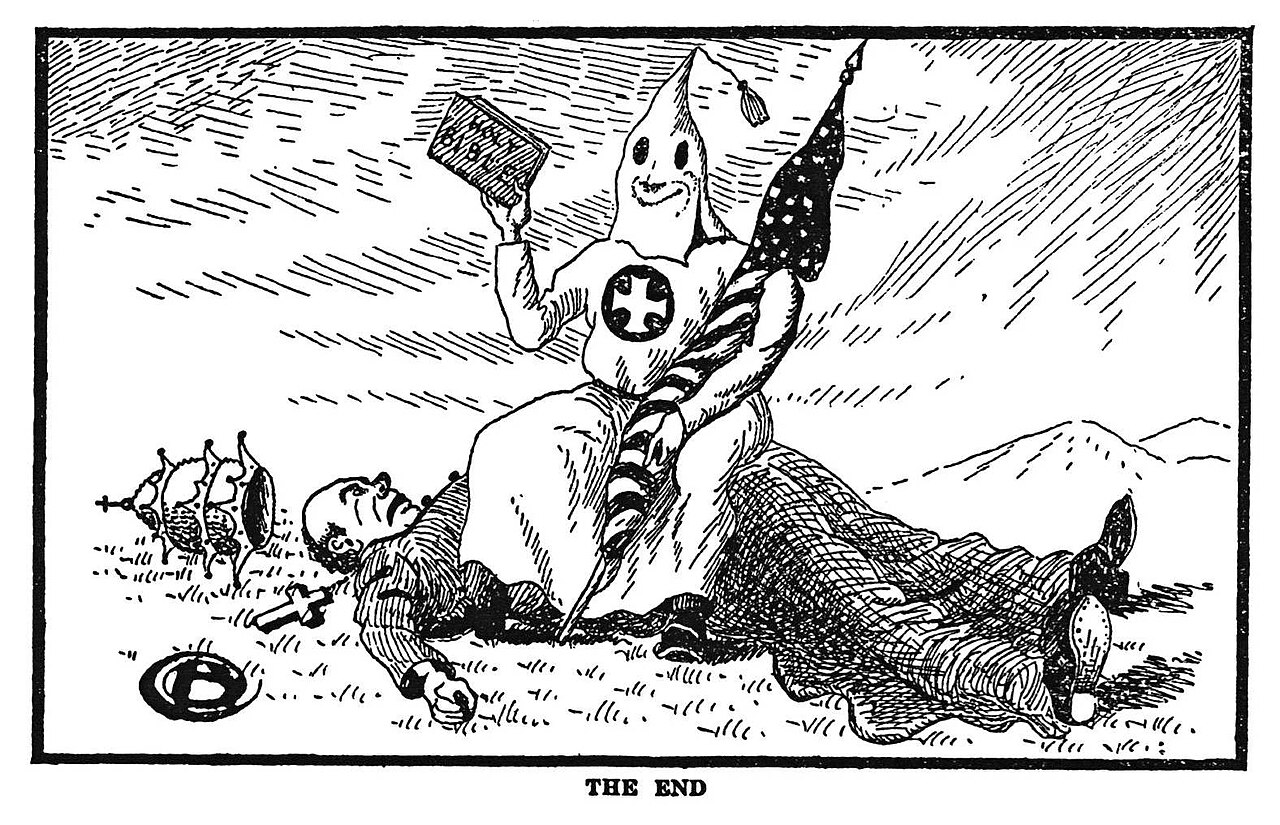

This second incarnation learned to sell itself. Dues, costume rentals, and ceremonies financed an organization that pitched “Americanism” while aiming squarely at Black citizens, immigrants, Catholics, Jews, and anyone labeled un-American by a militant Protestant script.

The 1920s: From Hate Group to Mass Movement

Membership soared into the millions. The Klan staged parades in capitals, endorsed candidates, and helped elect mayors, sheriffs, and legislators. Power ran both ways. Politicians sought its favor, and Klan officers sat in city halls. Boycotts, arson, and beatings enforced its “community standards,” and a simple visit by robed men could shutter a business or drive a family out by nightfall.

Beneath the moral posturing lay rackets and graft. Selling robes and titles turned hate into a cash business. dues funded private armies, and the promise of belonging masked the machinery of extortion. Two things kept the facade standing: a cause broad enough to include many bigotries and a culture that mistook intimidation for civic duty.

Then scandal ripped the curtain. In Indiana, Grand Dragon D. C. Stephenson’s abduction and assault of Madge Oberholtzer led to a murder conviction that shattered the Klan’s claim to virtue. His retaliation against former allies exposed bribes, blackmail, and political capture, prompting defections and investigations that cracked the movement’s veneer.

The fall was swift but not final. The network thinned, yet the ideology lingered, waiting for a new fight to ignite it.

The Third Klan: Open War on Civil Rights

Desegregation rulings and the modern civil rights movement brought a new wave of Klan violence. This time it looked less like a national order and more like a constellation of cells, united by a common enemy and a playbook of terror. Cross burnings and bombings became tools to block school integration, voting drives, and sit-ins.

The 1963 bombing of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church killed four girls and shocked a nation. The 1964 murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner in Mississippi exposed the deadly collaboration between some deputies and Klansmen who hunted civil rights workers on back roads. Each crime pushed federal authorities to act and the public to reckon with what “law and order” concealed.

Law, Lawsuits, and the Price of Terror

Federal agencies infiltrated Klan groups, indicted bombers, and used conspiracy charges when local juries refused murder verdicts. Civil rights laws gave prosecutors tools. Pressure mounted case by case, raid by raid, conviction by conviction. The effect was cumulative. Leadership ranks thinned. Recruiting slowed.

Then a grieving mother turned a lynching into financial judgment. After Michael Donald was murdered in Mobile in 1981, Beulah Mae Donald sued a Klan organization in civil court. The verdict bankrupted that faction and surrendered its headquarters to satisfy damages. The takeaway was simple and devastating: terror carries a price tag, and victims could collect.

Rebranding, Splintering, and the Far Right’s Ecosystem

By the late twentieth century, the Klan had fractured into small outfits with competing leaders and agendas. Some tried to dress up old hatred in cleaner clothes, trading robes for suits and swapping slurs for code. David Duke’s runs for office in the 1980s and 1990s modeled how to launder white supremacy into “heritage” rhetoric and talk-radio politics. Respectability was the costume; the program remained exclusion.

Other strands drifted toward paramilitary and neo-Nazi milieus, building compounds, stockpiling weapons, and fantasizing about race war. Groups like Aryan Nations cross-pollinated with Klan remnants and militia culture, turning bigotry into armed ideology. The family tree sprawled, even as the Klan label lost market share.

The internet completed the pivot. Forums and social platforms offered a cheap megaphone and a pipeline to radicalize loners at scale. The hood became a handle. The cross became a meme. While formal Klan numbers dwindled, the ideas migrated into a broader extremist ecosystem that learned to mix old dogma with new conspiracies.