A new kind of rescue and assault machine lifted off in 1956, then changed wars by the mid 1960s. The Bell UH-1, nicknamed “Huey” from its original HU-1 code, moved troops, ammo, and the wounded across jungle and mountain in minutes, not hours. By 1968, whole U.S. units planned around helicopter speed. Two wide doors, skids, and a tough engine made quick landings possible on rough ground. This guide uses dates, distances, and real specs to show how one helicopter reshaped the fight.

1. Birth of a Lifesaver, 1956–1959

Bell’s prototype XH-40 first flew on October 20, 1956 in Texas. The U.S. Army accepted the design in 1959 as HU-1, later redesignated UH-1. The nickname “Huey” stuck. Unlike small liaison craft, this turbine powered helicopter hauled real weight with room for medics and gear. Early tests proved that hot, humid air in Southeast Asia cut lift, so crews watched temperatures and loads. The wide sliding doors and skid gear let pilots touch down in clearings that measured only a few dozen yards across.

2. From HU-1 to “Huey,” A Name That Stuck

The original designation HU-1 meant Helicopter, Utility. Troops saw “HU-1” stenciled on airframes in 1959 and shortened it to “Huey.” In 1962, the Department of Defense switched to UH-1, but the nickname was already part of unit slang. Names matter, because clear labels speed orders on radios, especially in loud cabins. The Huey’s boxy doors, two blade rotor, and long tail boom made it easy to spot from 300 yards out, even through smoke. A simple, memorable name helped keep calls short and calm.

3. Medevac Breakthrough, “Dustoff” Saves Minutes

Medevac crews called “Dustoff” flew Hueys with red crosses, hoists, and litters. In Vietnam, response time often dropped to under 1 hour from injury to surgery, a huge change from earlier wars measured in hours. Pilots landed in tight “hot” zones while medics kept airways open and bleeding controlled. A UH-1 could carry 6 litter patients plus a medic, depending on heat and altitude. Crews used flare paths at night, then NVG systems arrived later. The goal was simple, lift fast, hand off fast, save lives.

4. Airmobile Tactics, Ia Drang 1965

Helicopters turned infantry into “airmobile” forces. In November 1965, the 1st Cavalry Division used Hueys to land at Landing Zone X-Ray in the Ia Drang Valley. Rotations moved companies in waves, each flight only minutes apart. The new plan traded long jungle marches for quick hops of 10 to 20 miles, with gunships circling above. Commanders learned to name and secure small landing zones, then leap again. Radios and colored smoke marked pickup points. That month showed how lift, speed, and timing could decide ground battles.

5. Lift and Firepower, Troops and Gunships

A typical UH-1H could lift about 11 troops plus crew in cooler morning air at low altitude. Door gunners fired M60 machine guns from mounts, while dedicated gunship versions carried 2.75 inch rockets and M134 miniguns. Crews balanced fuel, ammo, and heat to stay within limits. On approach, pilots flew 60 to 80 knots, then flared to a quick skid landing. Downwash threw dust and pebbles, so infantry crouched and kept eye protection on. Gunships orbited to suppress enemy fire during the short unloading window.

6. The Sound and the Rotor, Why “Wop Wop”

The Huey’s two blade, 48 foot rotor makes a “wop wop” beat that carries for miles. That sound comes from blade tips nearing transonic speed and the teetering rotor’s airflow pattern. Pilots watched rotor RPM on the tachometer and kept torque within limits to protect the gearbox. Skids, not wheels, simplified landings on dirt, sand, and pierced steel planking. A tail rotor at the boom’s end countered torque. Ground crews tied blades during storms to prevent “sailing,” a safety step taught on day one.

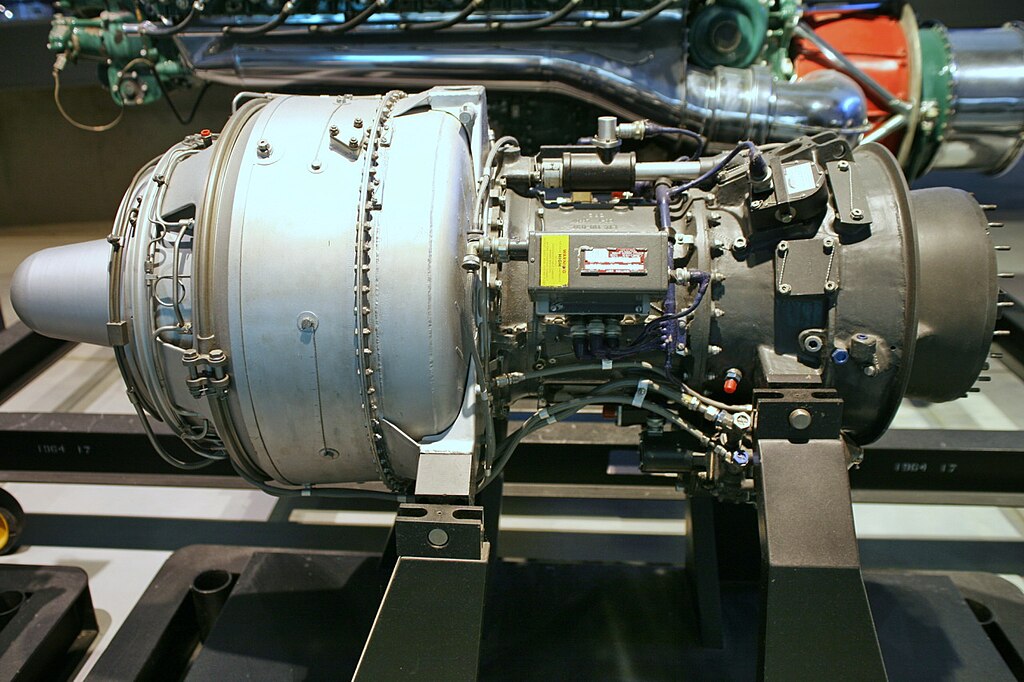

7. Engine Power and Range, Lycoming T53

Many Vietnam-era Hueys used the Lycoming T53 turbine. The UH-1H’s T53-L-13 produced about 1,400 shaft horsepower, enough to lift troops, water, or sling loads. Cruise sat near 125 knots, with a typical range of around 300 miles on internal fuel. High heat and high hills reduced performance, so crews planned carefully above 3,000 feet. Pilots managed fuel with simple gauges and set power by twisting the collective’s grip. The turbine’s smooth pull, compared to old piston engines, made quick climbs possible.

8. Crew, Training, and Maintenance Rhythm

A combat Huey usually flew with 2 pilots, a crew chief, and a door gunner. The crew chief was familiar with every panel and logged daily inspections, from chip detectors in the transmission to hydraulic lines beneath the cabin floor. Training flights practiced autorotation, a glide without engine power, to land safely if the turbine failed. Mechanics tracked hours on main components, replacing parts at set intervals. Even in muddy monsoon seasons, crews wiped sand from filters and checked skids for cracks before the next sortie.

9. Numbers and Losses, A Hard Price

Production topped 16,000 airframes across the Huey family. In Vietnam, thousands served from 1965 to 1973, and more than 3,000 were destroyed by combat and accidents. Those numbers show constant risk in hot landing zones, bad weather, and night flying. Armor plates around seats and self-sealing tanks improved survival, but the weight cut lifted, so units removed gear when the heat climbed. Memorials list tail numbers by year. Reading those plates at museums turns abstract totals into specific crews, routes, and missions that ended suddenly.

10. Life After War, Fire and Rescue Work

After 1975, many UH-1Hs moved to U.S. states, allies, and agencies. Fire crews fitted belly tanks and Bambi buckets to drop water on wildfires from Colorado to California. Police and rescue teams used hoists to lift hikers and flood victims. The Marine Corps moved to newer UH-1Y models after 2008, but the Huey shape still flies in several services and counties today. If you visit a static display, keep kids back from the tail rotor arc, and never climb skids without staff permission.