Some jobs shaped daily life in the United States, then vanished as machines and laws changed. Knowing them explains the rules we use now. From mill towns in 1810 to spaceflight checks in 1962, Virginia, these roles kept mornings on time, streets lit, food cold, and messages moving. Their end dates matter, like 1912 for a phosphorus ban and 2006 for the last U.S. telegram. They also show how standards, like 1883 time zones, grew from real problems. Use these lessons with schoolwork, teams, and first jobs today. Small details, such as inches of ice or posted routes, kept people safe.

1. Knocker-up

Knocker-ups woke sleeping workers by tapping windows with long poles, mostly in British mill towns like Manchester by 1810. The service spread across Lancashire in the 1850s, and some used pea shooters for upper floors. In the United States, mass alarm clocks became cheap in the 1920s, often under $3, so the job faded. This history reminds us to plan reliable wakeups. Teens can set two alarms, check volume on Sunday nights, and avoid risky tricks like climbing ledges or striking glass. Being on time helps teams and buses run smoothly.

2. Lamplighter

Lamplighters lit and doused gas streetlights at dusk and dawn, using ladders and flame on fixed routes. Cities began switching to electric lights in the 1880s after early tests in Cleveland in 1879 and New York soon after. By the 1910s the job was shrinking, and by the 1930s it was rare in U.S. towns. Their routines show how upkeep keeps streets safe. After storms, crews still inspect bulbs, timers, and lines. If your block goes dark, report it. Always keep distance from gas, use dry hands, and avoid sparking tools.

3. Ice Cutter

Before home refrigerators, crews cut lake ice each winter, then hauled 200 to 300 pound blocks into sawdust-cooled icehouses. Boston trader Frederick Tudor shipped New England ice to Havana in 1806, and even to Calcutta in 1833. Electric fridges spread after 1927 when GE released the Monitor Top, and the natural ice trade collapsed by the 1930s. This story shows timing and storage. Workers waited for at least 12 inches of clear ice and kept ropes ready. Cold water disables muscles fast, so lookouts used whistles near inlets where thickness could drop inches.

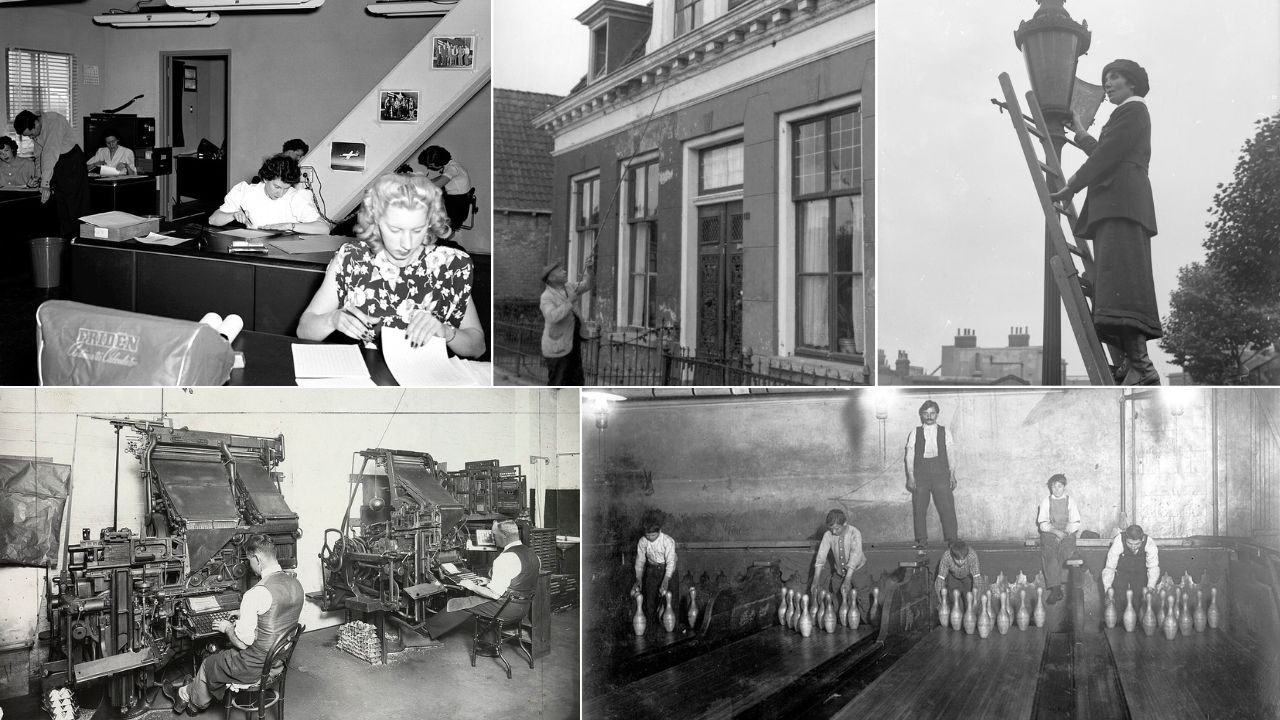

4. Bowling Pinsetter

Pinsetters once sat behind lanes to clear pins and reset racks by hand. Pay could be 5 to 10 cents per game in the 1930s. AMF introduced an automatic pinspotter in 1946, and by 1956 many centers used machines for spotting and ball return. Manual jobs faded across the United States. The change teaches balance, automation plus safety. Older alleys often top 85 dB, so ear protection helps. Follow posted lane rules, use guards, and wait for machines to stop. Managers log repair dates for belts and sensors to keep resets steady on busy weekends.

5. Morse Telegraph Operator

Morse telegraph operators sent messages over wire using dots and dashes. The first U.S. public line opened in 1844 between Washington, DC, and Baltimore, a 38 mile route. Operators learned around 25 words per minute and handled railroad and newspaper traffic. Railroads adopted standard time zones in 1883 to reduce collisions, and telegraph timing helped keep trains on schedule. Phones and teletype replaced the job. Western Union ended domestic telegrams in 2006. Clear formats still save time, so confirm city codes and dates before changes.

6. River Driver

River drivers guided floating logs down spring rivers using pike poles and spiked boots. Crews cleared jams that could stretch hundreds of yards, then walked miles along banks to keep timber moving to mills. As trucking and rail expanded, states ended the practice. Maine’s Kennebec River held its final log drive in 1976. The work shows how seasons set schedules. Ice-out in Maine often comes in April, which once triggered drives. Cold water and unstable logs can drown workers, so life jackets and throw ropes remain essential in river jobs.

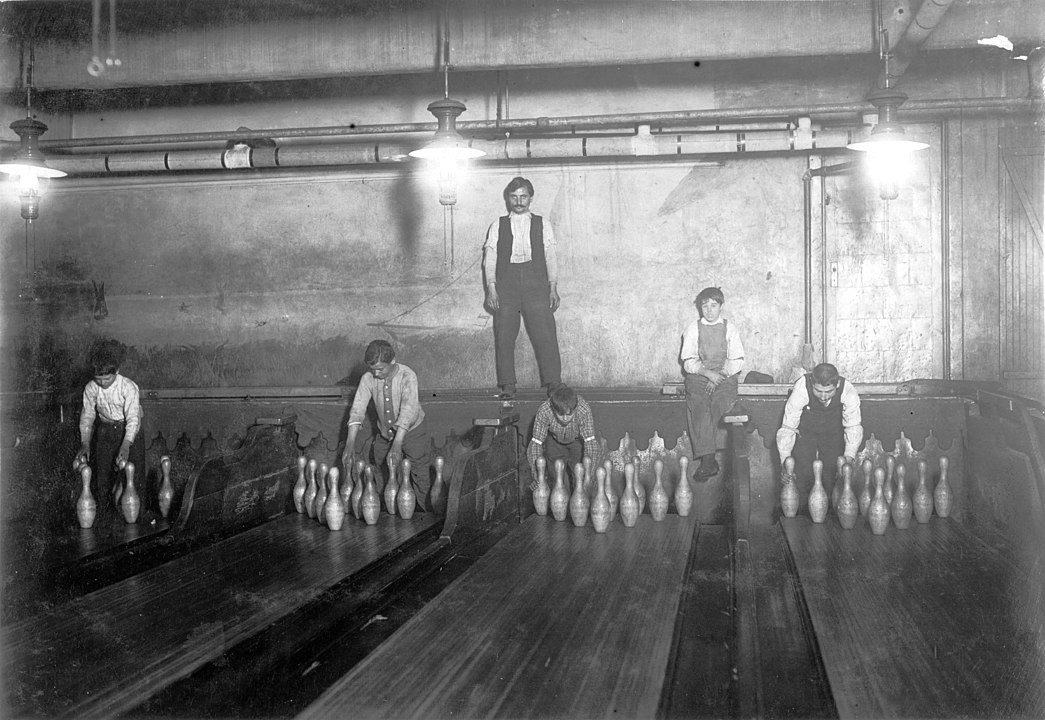

7. Linotype Operator

Linotype operators cast whole lines of hot metal type for newspapers and books. Ottmar Mergenthaler’s machine debuted in 1884 and boosted output in big city shops. Operators managed 550 degree Fahrenheit metal, matrices, and keyboards with more than 90 keys. Phototypesetting and digital layout replaced hot metal in the 1960s and 1970s. The New York Times ended hot metal in 1978. These details stress training and heat safety. Shops logged melt temperatures and checked extinguishers each month to satisfy codes and insurance rules.

8. Human Computer

Before electronic machines, human computers solved math by hand for engineering and science. At NASA’s Langley lab in Virginia, teams computed flight paths in the 1940s and 1950s. Katherine Johnson checked John Glenn’s 1962 orbital path, verifying early IBM results before launch. By the 1970s, digital computers replaced the job title. Independent checks still prevent errors. For labs and exams, write units like meters and seconds, then verify inputs. Slide rules were common in 1959. Many teams posted dated formula sheets to avoid mixups.

9. Matchstick Dipper

Match workers once dipped splints in white phosphorus, which ignited easily but released toxic fumes. The danger caused phossy jaw, a painful bone disease documented in London factories by the 1880s. Pressure grew for reform, and Britain banned white phosphorus matches in 1910. The United States followed with a federal tax and ban in 1912. Modern plants use safer chemistry like red phosphorus and strict ventilation. At home, store matches high and dry, and keep them away from small children and heaters to prevent fires.