The Harlem Renaissance reshaped American arts between 1918 and 1937. Northern cities drew Black writers, painters, musicians, and photographers. Harlem’s 125th Street buzzed with clubs, salons, and print shops. Magazines like The Crisis and Opportunity published new voices. Record buyers in 1925 paid 75 cents for race records that spread jazz and blues. Murals, novels, and portraits carried pride, protest, and style. These 9 creators worked in New York, Chicago, and beyond. Their dates, venues, and milestones still guide culture, classrooms, and stages across the United States today.

1. Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes arrived in New York in 1921 and published “The Weary Blues” in 1926. He mixed jazz rhythm with plain speech. Hughes read at the 135th Street branch library and wrote columns for The Chicago Defender in the 1930s. His poem “I, Too” claimed a seat at America’s table. Teens still study it in U.S. literature units. Hughes traveled to Mexico and Paris, but Harlem stayed central. He proved that 14 lines, clear verbs, and real voices could move crowds.

2. Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston studied anthropology at Barnard in 1927 and collected Black folklore in Florida towns along U.S. 441. Her novel “Their Eyes Were Watching God” appeared in 1937 with Eatonville as a model town. Earlier, she co-founded the journal Fire!! in 1926 on West 135th Street. Hurston’s field notes listed songs by title, dates, and counties. That method shaped her fiction’s sound. In classrooms, teens read her porch scenes to hear dialect, pride, and conflict without stage directions.

3. Aaron Douglas

Aaron Douglas painted sharp silhouettes and circles that looked like sunlight through stained glass. In 1934 he completed four murals, “Aspects of Negro Life,” for the 135th Street library. Panels show slavery, jazz, and migration with radiating lines. Born in 1899 in Kansas, Douglas taught design at Fisk University by 1937. He used flat shapes and measured angles, not fine brush hairs, to tell big stories. Teens who sketch posters can copy his arcs, stacks, and repeating rays.

4. Augusta Savage

Augusta Savage opened the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts in Harlem in 1932. She taught young artists for low fees and wrote names in class lists by month. Her 1939 New York World’s Fair sculpture, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” stood 16 feet tall. Born in Green Cove Springs, Florida, in 1892, she studied in Paris in 1929 after winning a scholarship. Casting bronze was expensive, so many works survive only in photos. Her career proved why funding and space matter.

5. Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Lawrence trained at the 135th Street library workshop, then painted the “Migration Series” in 1940–1941. It includes 60 panels, each with a caption about trains, jobs, and Jim Crow. Lawrence moved to Harlem at age 13 in 1930 and studied color blocks, not tiny details. Tempera on hardboard dried fast, so he worked in batches to keep hues even. Museums later split the series, 30 panels each in two cities. The set remains a map in pictures and numbers.

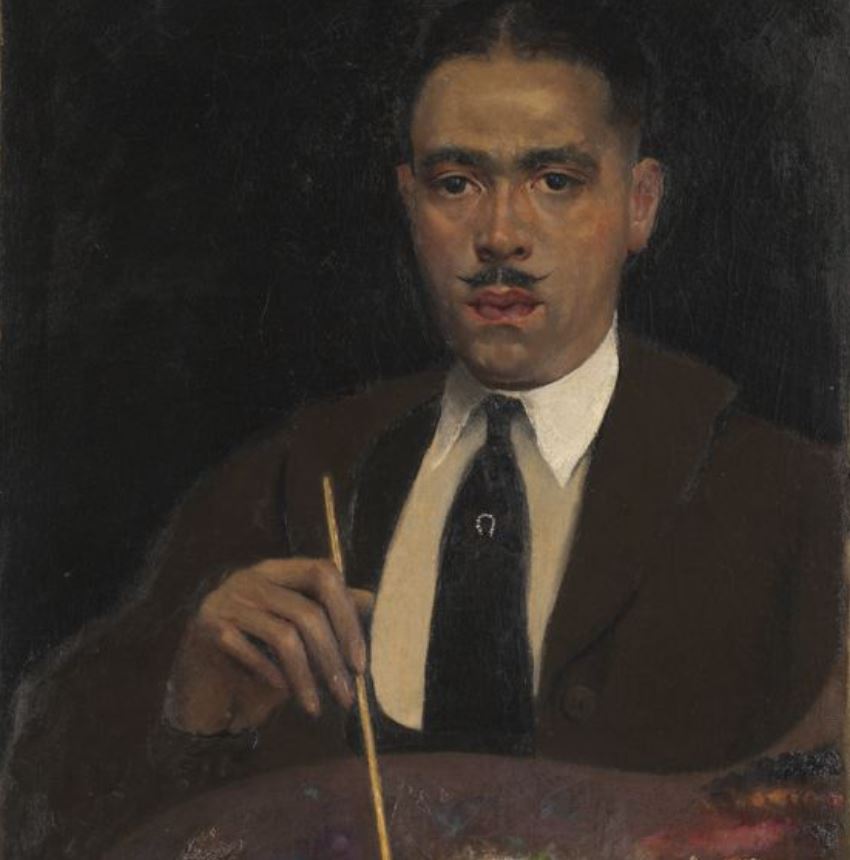

6. Archibald Motley Jr.

Archibald Motley Jr., born in New Orleans in 1891, painted Chicago nightlife with electric color. His 1930 canvas “Blues” shows dancers, horns, and bright neon angles. Motley trained at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and won a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1929. He visited Paris in 1929–1930 and sketched cafés by the clock. Back home, he used crimson and cobalt to frame faces and hats. His scenes match beat counts, like 4 bars per phrase, across the dance floor.

7. James Van Der Zee

James Van Der Zee photographed weddings, jazz bands, and families in his Harlem studio on 135th Street. He opened his first studio in 1916 and printed portraits with careful retouching. In 1924 he documented the Marcus Garvey parade with floats and dates stamped on prints. Van Der Zee preferred 8×10 negatives for detail. He added painted backdrops and soft light to lift faces. His archives show that captions with names, street numbers, and years preserve memory better than guesses.

8. Duke Ellington

Duke Ellington led his orchestra at the Cotton Club on 142nd Street from 1927 to 1931. Radio broadcasts carried his sound nationwide at 9 p.m. slots. Arrangements like “Mood Indigo” used muted trumpets and low clarinets. In 1932 his band toured Europe, then returned to Harlem stages. Ellington wrote charts by measure numbers so parts fit exactly. Teens in school bands still count 4 beats per bar the way his players did nightly under bright club lights.

9. Bessie Smith

Bessie Smith, crowned the Empress of the Blues, recorded for Columbia starting in 1923. Her discs sold in the tens of thousands when a single cost under $1. Though she lived mainly on the road, her records played in Harlem apartments and clubs. Songs like “Downhearted Blues” ran about 3 minutes, the limit of 78 rpm sides. Smith’s huge voice did not need microphones. She shows how stage craft, breath control, and careful timing can fill a hall without modern gear.