The holidays once tasted different. Across immigrant kitchens, church basements, and small-town diners, cooks leaned on seasonal scarcity, slow methods, and ritual. Winter citrus felt rare, cream was a splurge, and spices signaled celebration. Families stirred, steamed, and ladled recipes that tethered memory to the calendar. What this really means is that a handful of dishes quietly slipped from everyday tables as convenience grew. Revisiting them restores textures, aromas, and stories that shaped cold-weather gatherings.

Oyster Stew

A Christmas Eve standby in many Irish American and Southern homes, oyster stew linked celebration to winter’s safe shipping window. Before refrigeration, cold snaps made inland oysters possible only once a year, turning the first pot into a seasonal marker. Milk or cream, butter, and briny liquor built a simple, shimmering broth finished with black pepper and parsley. The hush of steaming bowls, fogged panes, and quick work at the stove set the night’s beginning.

Syllabub

A Tudor invention that crossed the Atlantic, syllabub married wine, cream, sugar, and lemon into a lightly curdled froth. Colonial cooks served drinkable versions in cups and whipped styles as a snowy topping for cakes and fruit. The delight was texture as much as taste, a buoyant foam collapsing slowly in the cold. As restaurants favored showier finales and homes leaned on shortcuts, this bright, spirited finish faded from holiday tables despite its effortless charm.

Wassail

Wassail functioned as both toast and bowl, a shared ritual as much as a recipe. Mulled ale or cider simmered with apples, spice, and citrus, then arrived at the table blazing hot. Neighbors became a chorus, voices rising as the ladle passed and the room scented itself with clove and peel. By the late 18th century it sat beside roasts and puddings on formal menus, proof that hospitality could be rustic, communal, and grand.

Mince Pie With Real Meat

Older mincemeat truly meant meat. Beef or venison joined suet, dried fruits, and warm spice, creating a glossy, deeply seasoned filling that read savory and sweet at once. The pie held its own next to gravies and greens, not just desserts. Shelf-stable jars and gentler palates later nudged fruit-only versions into dominance. The original captures winter thrift and ceremony in a single slice, sturdy enough for travel, fragrant enough to perfume an entire room.

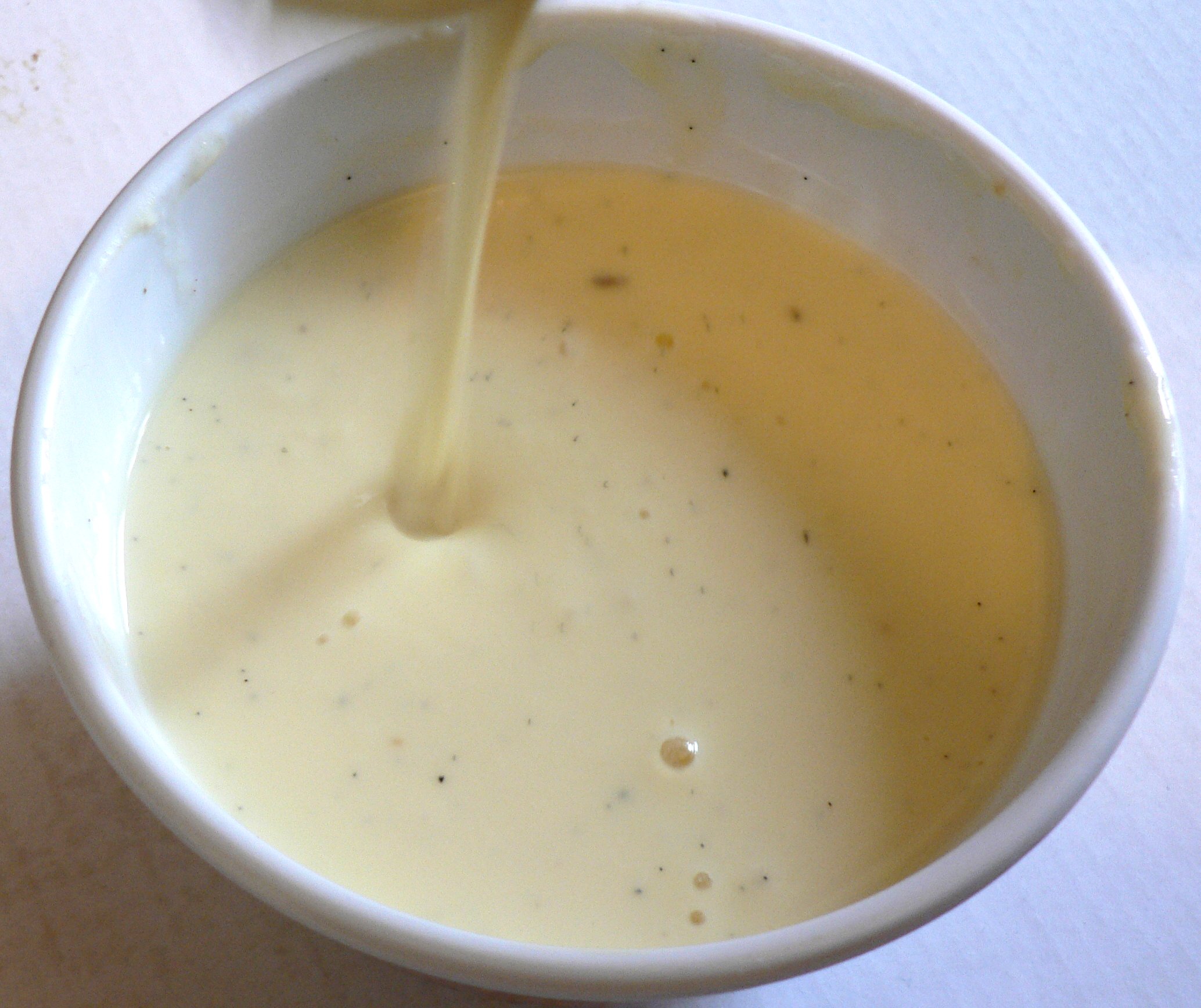

Boiled Custard

In Southern homes, boiled custard lived between beverage and dessert, a silken pour of milk, yolks, sugar, and vanilla. It demanded low heat and steady stirring until the spoon coated perfectly, then a cool rest beside coconut cake and ambrosia. The store carton eventually displaced the ritual, but the homemade version still teaches control and patience. One careful simmer, one clean nappe, and the room quiets as a simple sweetness settles the table.

Ambrosia

Ambrosia balanced heavy roasts with light, fragrant brightness. Fresh oranges and coconut, sometimes pineapple, rested with a little sugar until the fruit glossed and the coconut softened. The result tasted like winter sunlight and sounded like family work: segmenting citrus, catching juice, folding gently. Nineteenth-century menus prized that restraint. Later, marshmallows and canned syrup crowded the bowl, and the original slipped away, even though its clean flavors still cut through salt, fat, and spice.

Plum Pudding

Plum pudding meant dried fruits, suet, spice, and time. Families mixed the dense batter on Stir up Sunday, each person taking a hopeful turn, then rested it for weeks before a long steam. The glossy dome sometimes arrived under a brief blue flame, a small theater before custard and slices. Labor made it special, and scarcity made it sensible. As calendars sped up, the ritual thinned, and the pudding moved from centerpiece to memory.

Tom And Jerry

A 19th-century American cousin to eggnog, Tom and Jerry turned whipped eggs, sugar, and spice into a warm barroom and parlor ritual. A jar of batter waited by the stove, ready to meet hot milk, rum, and brandy in thick, fragrant mugs. The drink felt lively and restorative, social by design, common across the Midwest and Northeast. Streamlined menus and changing home habits dimmed the ceremony, and the bowl and ladle quietly retired.