Some of the most useful things arrived by mistake, not by plan. A petri dish left out too long. A melted candy bar near a humming magnetron. A weak glue that would not quit. Each mishap asked for attention, not shame, and a patient eye turned error into insight. What this really shows is grit. Curiosity, tidy notes, and a second look can turn the wrong turn into a new road, then into tools the world now depends on. Surprise is a fine starting line.

Penicillin

Alexander Fleming came back from vacation to a messy lab and noticed mold on a culture plate. Around the mold, bacteria had vanished, a clean halo that refused to lie. He isolated the substance and called it penicillin, the first antibiotic. The discovery felt like luck at first, then like obligation, because the pattern held across plates and days. An untidy bench, sharp eyes, and patience turned a spoiled dish into medicine that would rewrite hospital wards and save millions.

Microwave Oven

In a radar lab in 1945, engineer Percy Spencer leaned close to a magnetron and found a melted candy bar in his pocket. The radio waves had agitated water and fats, cooking from the inside out. He tried popcorn, then an egg, then a metal box to contain the energy. What began as a sticky surprise became the microwave oven, a fast, compact stove that moved from factory floors to office break rooms, tiny home kitchens, dorms, and late nights after long shifts.

Post-it Notes

Chemist Spencer Silver developed a weak adhesive that refused to fully cure. It stuck, then lifted, then stuck again, the opposite of what industry wanted. Years later, colleague Art Fry needed a bookmark for choir that would not fall out. He brushed Silver’s glue on scrap paper and found a reusable note that gripped without ripping pages. Office drawers filled with neon squares after that, turning a near failure into a tool for memory, planning, and quiet collaboration.

X-Rays

In 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen noticed a strange glow from a coated screen while he experimented with cathode rays behind a shield. Invisible rays were slipping through cardboard and cloth, painting bones and rings on plates. He called them X-rays, the unknown kind. Within months, surgeons could see fractures before cutting, and engineers could inspect metal without prying it apart. A lab accident widened human sight, trading guesswork for images and changing medicine and industry in a single stroke.

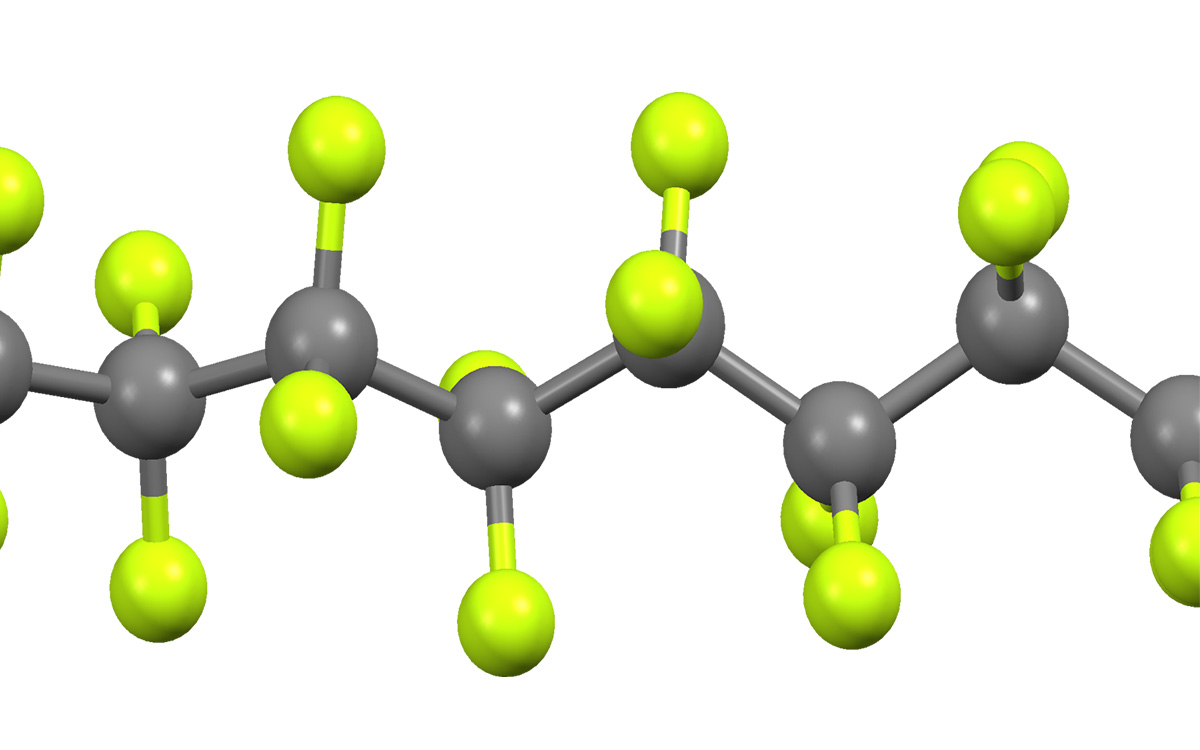

Teflon

Roy Plunkett was testing refrigerants in 1938 when a gas cylinder refused to release its contents. Inside, the tetrafluoroethylene had polymerized into a slick white solid that nothing seemed to stick to. It resisted heat, chemicals, and friction, a combination that felt impossible. The material became polytetrafluoroethylene, known as Teflon, and later lined nonstick pans, cables, gaskets, and valves. A stuck valve had become a shield, a thin film that still keeps surfaces clean and moving.

The Pacemaker

Engineer Wilson Greatbatch reached for a resistor in 1956 and grabbed the wrong value. The circuit pulsed in a slow, steady rhythm that sounded like a heart. He realized the mistake had built a timing engine that could pace a failing beat. With surgeons, he refined the device into a small, implantable aid. First tests brought quiet chambers and careful listening, then longer walks and fuller lives. An error in a parts drawer gave cardiology a new way to keep time.

Safety Glass

French chemist Édouard Bénédictus dropped a glass flask in 1903 and it hit the floor without exploding into shards. The inside had been coated with celluloid, which held the fragments in place. He turned the surprise into laminated glass by sandwiching plastic between sheets, a design that kept windows intact under stress. Automobiles, goggles, and storefronts adopted the idea. A lucky drop redrew the line between break and hold, turning brittle walls into barriers that fail more gently.

Super Glue

Harry Coover worked with cyanoacrylates during wartime research and found them impossible to handle. They grabbed everything, including instruments, and seemed useless. Years later the same chemistry was revisited and finally framed as a feature. A drop bonded instantly without heat or pressure. The adhesive became Super Glue, mending toys, tools, and hairline cracks, and later found medical uses in controlled forms. A lab nuisance became a household fix, proof that annoyance can hide possibility.