Public trust snaps faster than policy. Voters will argue over taxes and wars, but they rarely forgive leaders who deny, deflect, and then get caught. Across systems and decades, careers ended not over envelopes of cash but over untruths about conduct, credentials, or rules everyone else had to follow. The pattern is simple and brutal. Say what is not true about something core to the job, and the title evaporates. Institutions may move slowly, yet once credibility goes, the exit comes quick.

John Profumo, United Kingdom

In 1963, the secretary of state for war told the House of Commons he had no improper relationship with Christine Keeler. Weeks later, he admitted the statement was false, resigned from the government, and gave up his seat. Parliament formally ruled he had committed a grave contempt for misleading MPs. The episode reshaped Britain’s expectations of ministerial honesty and helped sink the government’s standing. The damage was ethical, not financial, and it proved terminal.

Boris Johnson, United Kingdom

After lockdown-era gatherings in Downing Street, a cross-party committee concluded in June 2023 that the former prime minister deliberately misled Parliament. He quit as an MP before the report was published, then attacked the process as political. The Commons later endorsed the findings with a wide margin. Whatever the rhetoric, institutions judged the deception intolerable, and the exit closed the door on immediate ambitions. Credibility, not cash, wrote the ending.

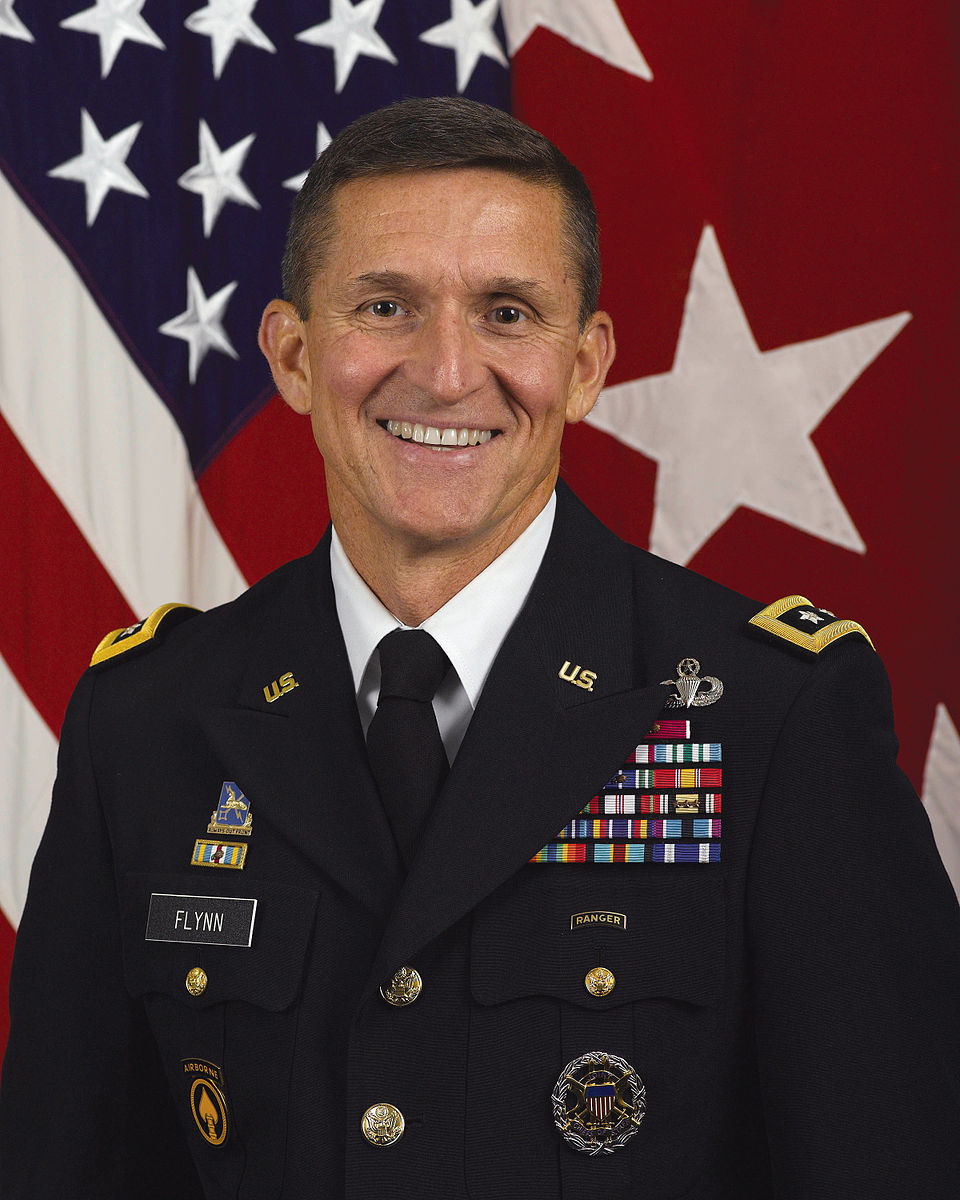

Michael Flynn, United States

The national security adviser lasted 24 days. He resigned in Feb. 2017 after acknowledging he misled the vice president about calls with Russia’s ambassador during the transition. The White House labeled his position unsustainable because trust at the top had fractured. Legal questions lingered, but the job ended over an ethical breach: inaccurate assurances about sensitive contacts. In security roles, credibility is oxygen; once it’s gone, nothing else matters.

Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, Germany

Germany’s defense minister resigned in March 2011 after the University of Bayreuth stripped his doctorate and investigators documented extensive plagiarism. He initially dismissed the claims, then apologized as evidence mounted and public trust collapsed. In a country that treats academic integrity as public service’s backbone, the issue was disqualifying. The fall centered on honesty in scholarship, not money or policy.

Annette Schavan, Germany

In 2013, the federal education minister stepped down days after her university revoked her Ph.D. for plagiarism. She denied intent but accepted that she could not credibly lead research and universities while contesting the finding. The message was clear: in portfolios built on knowledge and standards, academic deception ends authority. Integrity came first, résumé second, and the cabinet seat followed the degree out the door.

Pál Schmitt, Hungary

Hungary’s president resigned in 2012 after Semmelweis University withdrew his doctoral degree, concluding that much of his thesis lacked proper citation. He had resisted pressure, but public opinion and institutional censure made the office untenable. The role was ceremonial; the standard was not. A head of state under a cloud of misrepresentation could not function, so he quit to end the standoff.

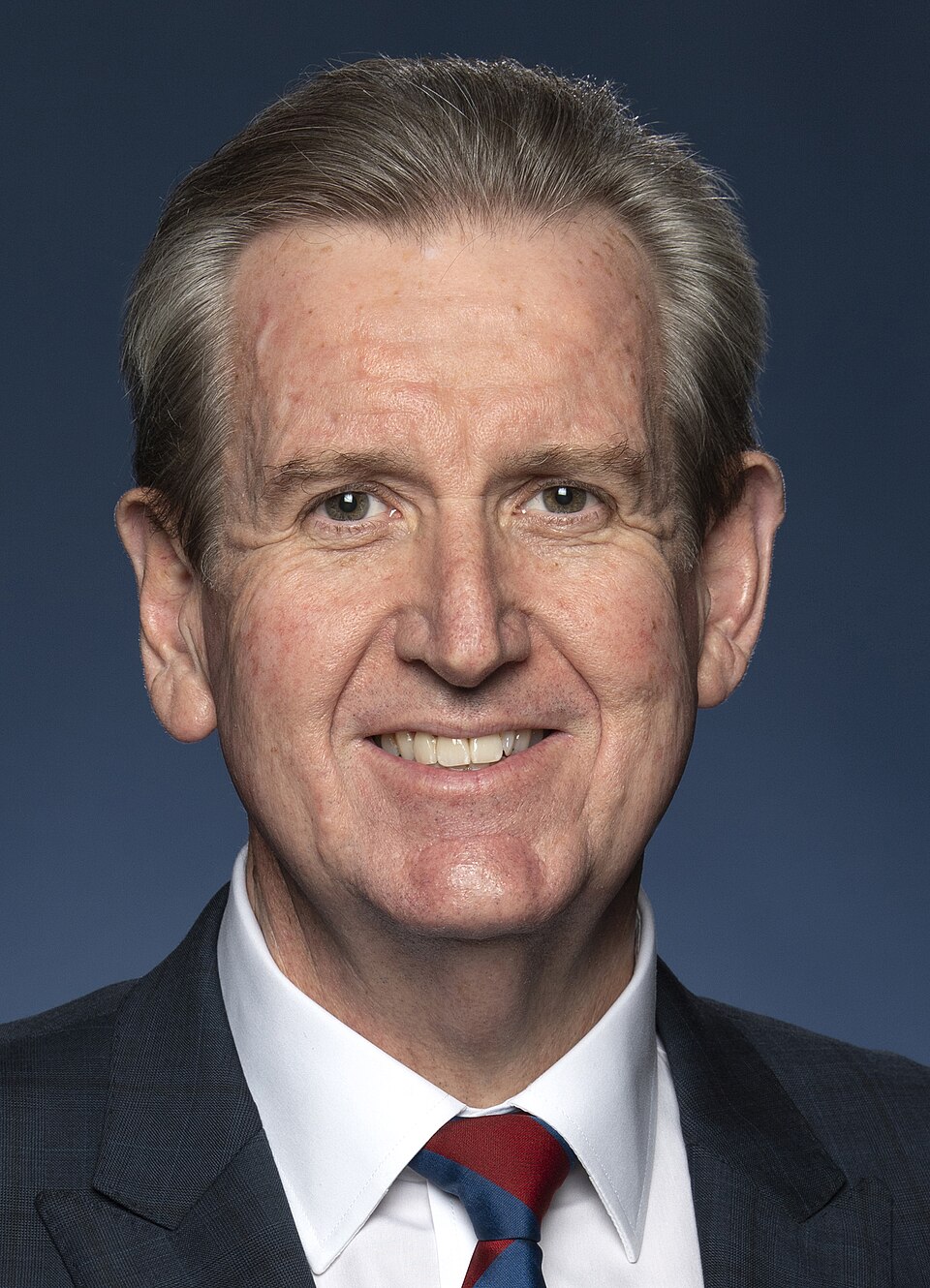

Barry O’Farrell, Australia

New South Wales’ premier told an anti-corruption inquiry he did not receive a $3,000 bottle of wine. A thank-you note surfaced the next day. He framed it as a memory failure, not corruption, and resigned within hours. The speed of the exit showed how providing inaccurate testimony to an integrity body can be career-ending on its own, even without a money trail or charge. Accuracy under oath is the line.