The Civil Rights Movement is often seen as a brief moment of speeches and marches, but its reality was broader and deeply connected to struggles still unfolding today. Myths simplify the work, the people, and the scope of change. In truth, the fight spanned decades, reached every corner of the country, and involved people from many walks of life. Understanding what really happened shows how its lessons still guide activism and community action now.

1. It Was Only About The 1960s

The 1960s delivered landmark wins, but the movement’s origins reached far earlier. Court cases in the 1930s and 1940s, labor strikes, and protests in the 1950s laid the foundation for later victories. The work continued into the 1970s and beyond, influencing campaigns for voting rights, housing, and education reform. Viewing it as a single decade hides the persistence, strategy, and multigenerational dedication needed to push real, lasting change forward across the nation.

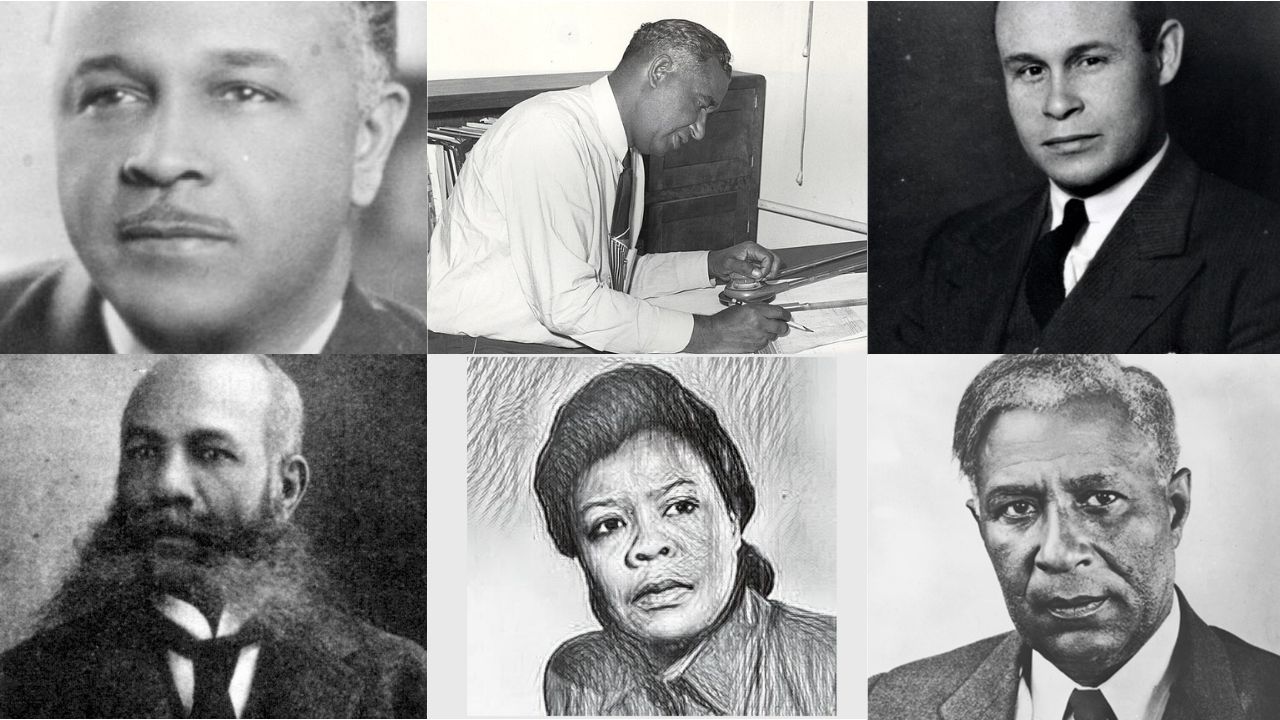

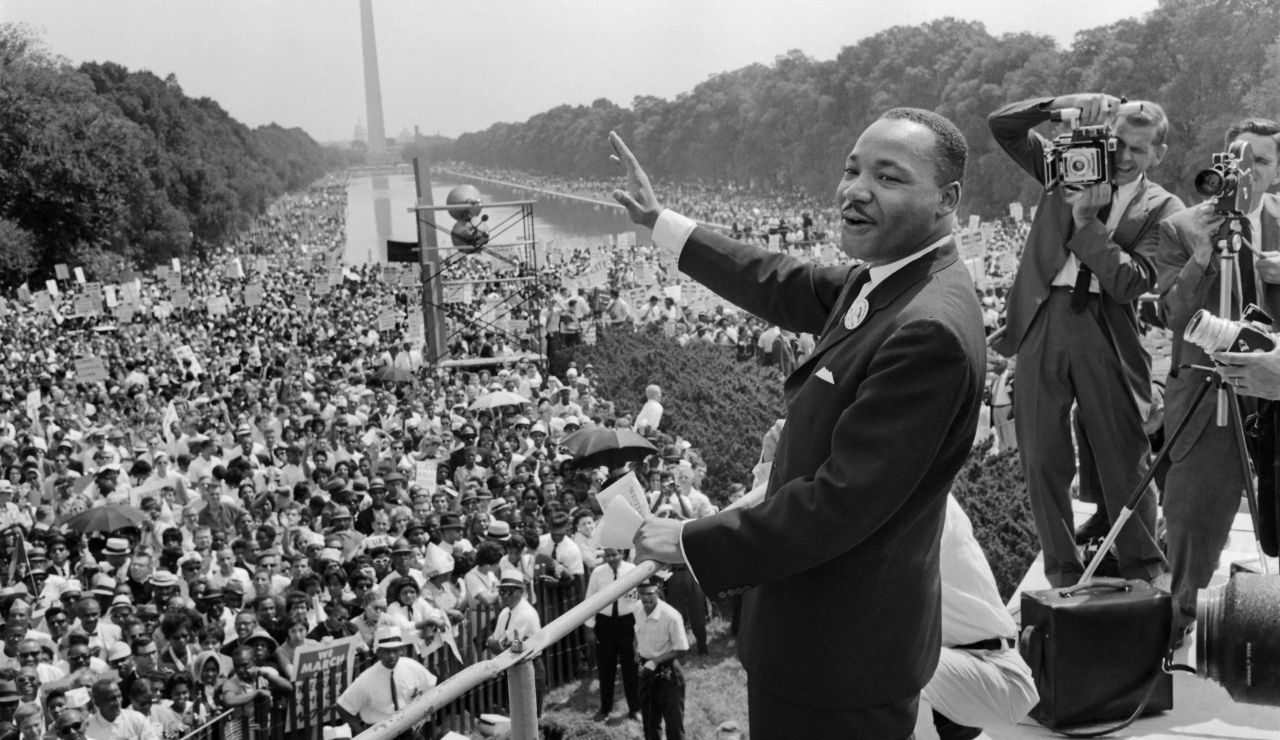

2. Martin Luther King Jr. Was The Only Leader

Martin Luther King Jr. played an iconic role, yet the movement relied on many influential voices. Ella Baker championed grassroots leadership, Bayard Rustin organized the March on Washington, and Diane Nash led campaigns across the South. Thousands of local activists, often unknown, mobilized neighbors, organized voter drives, and kept momentum alive. Like modern movements, it thrived because leadership was shared, proving that collective effort creates a stronger, lasting push for justice.

3. It Was Entirely Peaceful

Nonviolence was the guiding principle, yet the reality on the ground was more complex. In dangerous areas with little legal protection, some activists turned to armed self-defense. Groups like the Deacons for Defense and Justice guarded communities and marchers from violent attacks. This mix of peaceful protest and practical protection reflected the movement’s adaptability. Similar strategies are seen today, where peaceful marches are supported by legal teams and security for vulnerable participants.

4. It Solved All Major Racial Problems

The Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act ended legal segregation, but inequality persisted. Disparities in income, housing, healthcare, and education continued shaping the lives of many. Structural barriers took longer to dismantle, requiring ongoing activism. Understanding these modern struggles as part of unfinished civil rights work shows why action remains essential for achieving lasting equality.

5. Young People Played Only A Minor Role

Far from the sidelines, students often sparked the most visible actions. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organized sit-ins, freedom rides, and voter registration drives, mobilizing thousands of teens and college students. Many faced arrests, violence, and academic consequences for their activism. Their courage parallels today’s youth-led climate, gun safety, and social justice protests, proving young voices can challenge entrenched systems and inspire large-scale change across the nation’s political and cultural landscape.

6. Only African Americans Participated

African Americans were at the heart of the struggle, but allies from diverse racial, cultural, and religious backgrounds marched, provided legal assistance, and helped organize campaigns. White, Latino, Asian American, and Native American supporters contributed resources, skills, and visibility. This broad coalition strengthened the movement, just as diverse alliances fuel today’s fights for social, environmental, and economic justice. Cross-community solidarity remains a powerful tool for achieving lasting, systemic change in America.

7. The Government Always Supported The Movement

Federal support often came reluctantly and only after intense pressure from activists and widespread media coverage. Presidents and lawmakers feared political backlash and acted cautiously, delaying responses to urgent injustices. It took massive protests, legal challenges, and sometimes international embarrassment to push the government toward meaningful action. This pattern still exists, where grassroots movements must apply sustained public pressure before leaders commit to real policy changes that reflect moral and legal responsibility.