Classrooms are often where legends accidentally turn into lessons. A diagram or catchy line makes an idea easy to remember, and over time it hardens into something that feels official, even when research quietly moved on years ago. Some of the most familiar “facts” taught about space, animals, or history now sit on shaky ground. Looking back at them is less about blame and more about curiosity, a chance to see how knowledge changes and why that should be comforting.

Goldfish Have Three-Second Memories

Generations of students grew up joking that goldfish forget everything almost instantly, as if the animal resets with each lap around the bowl. Behavioral studies show that goldfish can learn mazes, remember feeding times, and recognize patterns for weeks or months. Some can even be trained to respond to sounds. The myth stuck because it was funny and convenient, but it shrinks a surprisingly capable little brain into a punchline that never really matched the evidence.

Tongues Have Separate Taste Zones

The neat taste map with sweet on the tip, bitter at the back, and strict borders often appeared in early science lessons. Modern work on taste buds shows that receptors for sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami are scattered across most of the tongue, with only small differences in sensitivity. No region is locked into a single flavor. The old chart survived because it was easy to draw and label, even though it oversimplified how mouths actually work.

Humans Use Only Ten Percent Of The Brain

The idea that most of the brain sits untouched hints at secret genius waiting to be unlocked, which made it irresistible in classrooms and pop culture. Brain scans tell a more grounded story. Even during rest, networks across the brain stay active, handling memory, movement planning, and constant background processing. Damage to tiny regions can change personality or abilities. Instead of a mostly empty warehouse, the brain looks more like a crowded city that rarely goes quiet.

Chameleons Change Color Only To Match Backgrounds

School projects once treated chameleons as pure camouflage experts, fading into leaves or bark purely to hide. Research on their skin shows something richer. Specialized cells and crystal structures let them shift colors for temperature control and social signaling as well as blending in. A bright pattern can signal aggression or courtship, not just a better disguise. The myth clung on because it fit a dramatic story, even as real animals went on using color as a language.

Bats Are Completely Blind

Many students leave basic biology convinced that bats flap around in total darkness, guided only by echoes. In reality, most bats have working eyes and can see reasonably well, especially in low light. Echolocation offers extra precision, letting them chase insects or weave through cluttered spaces, but it does not replace sight. The phrase “blind as a bat” turned out to be backwards. These animals navigate with a layered toolkit, not with a single desperate sense.

Sugar Always Makes Children Hyper

Classroom folklore often warned that sugary snacks would guarantee chaos by the end of the lesson or party. Controlled trials have struggled to find a reliable link between sugar and hyperactivity in most children. Parents and teachers who expect wild behavior after sweets are more likely to interpret ordinary energy as extreme. None of this means sugary diets are harmless, only that the story was tidier than the biology. Sleep, environment, and temperament matter at least as much.

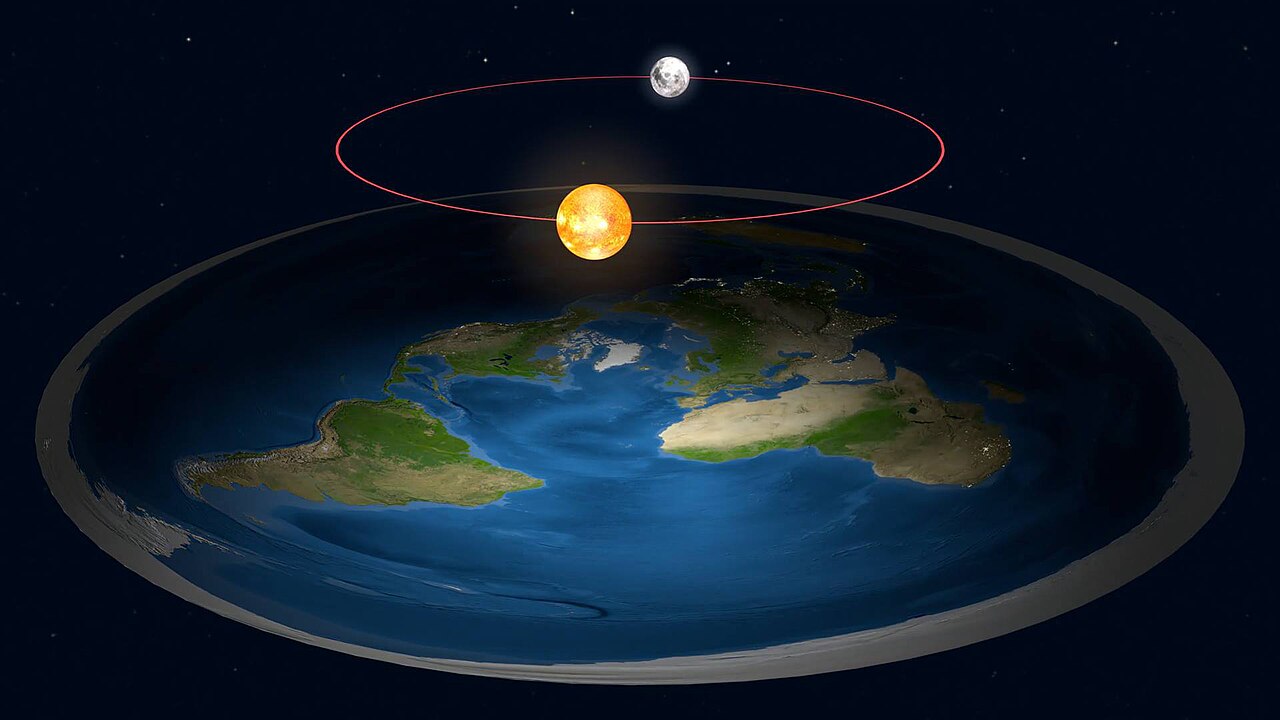

Seasons Happen Because Earth Is Closer To The Sun In Summer

Many diagrams quietly imply that summer arrives when Earth moves closer to the sun, with a stretched orbit driving temperature. The real explanation comes from the planet’s axial tilt. As Earth orbits, different regions lean toward or away from sunlight, changing the angle and length of the day. That is why January can mean winter in one hemisphere and high summer in the other. Distance changes slightly over the year, but tilt does nearly all the work.

Columbus Proved People Thought Earth Was Flat

A familiar school story paints Christopher Columbus as the lone believer in a round Earth surrounded by skeptics who feared he would sail off an edge. Historical records show that educated Europeans had accepted a roughly spherical Earth for centuries, drawing on ancient astronomy and navigation. The real dispute was about size and distance, not shape. Columbus underestimated the planet and stumbled into the Americas. The flat Earth tale survived because it made a cleaner heroic narrative.

Dinosaurs Were All Slow, Swampy Reptiles

Older textbooks sketched dinosaurs as sluggish, tail-dragging reptiles that lurked in steamy swamps. Fossil trackways, bone structures, and evidence of feathers have since redrawn that entire world. Many species appear to have been active, social, and capable of fast movement. Some likely regulated body temperature in complex ways, closer to birds than to modern lizards. Nesting sites suggest parental care. The picture shifted from clumsy monsters to an energetic, varied ecosystem that looked far more alive.

Humans Evolved From Monkeys In A Straight Line

Many posters show a single line of figures, moving neatly from stooped ape to upright modern human, suggesting that people literally descended from today’s monkeys. Evolutionary biology instead describes a branching tree. Humans and modern monkeys share older common ancestors rather than sitting at different steps on one ladder. Several hominin species overlapped in time, and many branches ended in extinction. The straight line image stayed because it fit on a wall, not because it fit the data.

The Great Wall Of China Is The Only Man-Made Object Visible From Space

School trivia often casts the Great Wall as the lone human structure visible from space, a claim that sounds grand but does not match astronaut reports. From low Earth orbit, wide features such as city grids, highways, and farmland patterns often stand out more clearly than a narrow stone wall that blends with the landscape. With cameras and the right conditions, parts of the wall can be seen, but it is not unique. The myth persists out of habit.

Lightning Never Strikes The Same Place Twice

The phrase shows up in lessons and speeches as a metaphor for unlikely events, and it can slip into weather talk as if it were a rule. Careful records reveal that tall buildings, towers, and isolated trees can be hit many times in a single decade, sometimes within one storm. Lightning follows conductive paths and storm structures, not poetic guidelines about fairness. The saying survived because it was catchy, even while actual storms kept ignoring it.

Vikings Wore Horned Helmets Into Battle

Textbook illustrations and school plays often march Vikings across the page in horned helmets, turning them into instant fantasy warriors. Archaeological finds tell a simpler story. Practical helmets used in combat were typically plain and hornless, built to protect rather than impress. Decorative horned headpieces from earlier ritual contexts were later mixed into Viking imagery by artists and costume designers. Classrooms then picked up that artwork, passing on stage designs as history without meaning to.