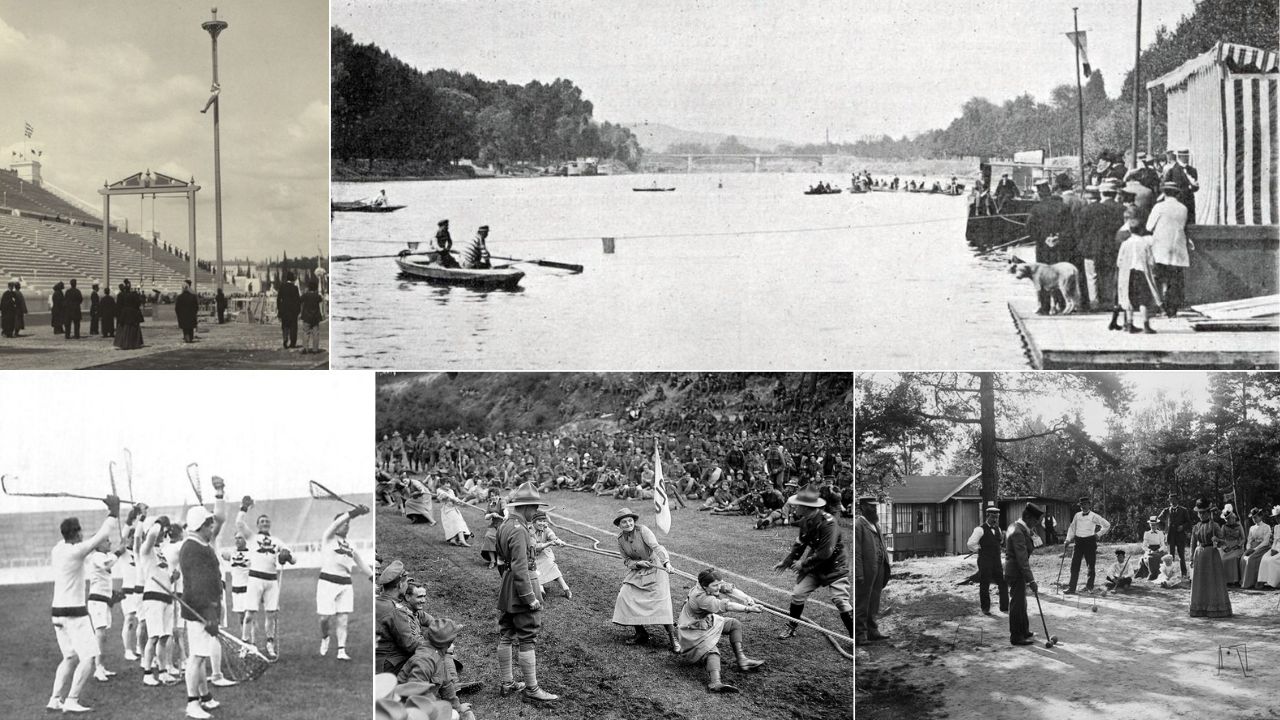

Before world wars reshaped the Games, the Olympics tested quirky and regional sports alongside track and swimming. Many events vanished for practical reasons: too few nations played, hard-to-officiate rules, high costs, or poor crowds. This list tours 12 pre-war events, from tug of war to underwater swim, and explains why each faded. Expect surprising rules, odd venues, and lessons about how the IOC refines the program to match global reach and safety.

1. Tug of War (1900-1920)

Teams pulled a hemp rope until a center marker crossed the line, best of three pulls. Club-based entries and uneven rules made competition messy across early Games. Great Britain dominated in 1908, while Sweden won in 1912. After 1920, the event disappeared as the IOC favored sports with international federations, standardized weight classes, and clearer officiating. Some matches featured mixed-club teams and spiked boots for traction, raising fairness questions. Debate over team size and match length lingered for years, and television-era spectacle later favored mats and lanes over muddy pits.

2. Croquet and Roque (1900, 1904)

Paris 1900 hosted croquet; St. Louis 1904 featured roque, an American variant played on hard courts. Tiny fields and low spectatorship hurt both. Croquet allowed mixed-gender entries, but few nations fielded teams. Lack of international clubs and tepid ticket sales convinced organizers these lawn games lacked global pull for future Olympiads. Spectator counts were tiny by modern standards, and formats varied between singles, doubles, and long lawn circuits. Without global federations promoting youth pathways, interest faded quickly after the novelty of early inclusion wore off.

3. Live Pigeon Shooting (1900)

In Paris 1900 competitors shot live pigeons in trap-style rounds. Reports tallied hundreds of birds killed and feathers littering the infield. Public backlash followed and clay targets replaced animals in later years. Ethical concerns and messy logistics ensured the event never returned as the Games aligned with humane standards and cleaner venues. Clean up demands were high and scoring disputes were common when birds flew erratically. Standardized clay targets later allowed safer ranges, consistent flight paths, and humane competition acceptable to broader audiences.

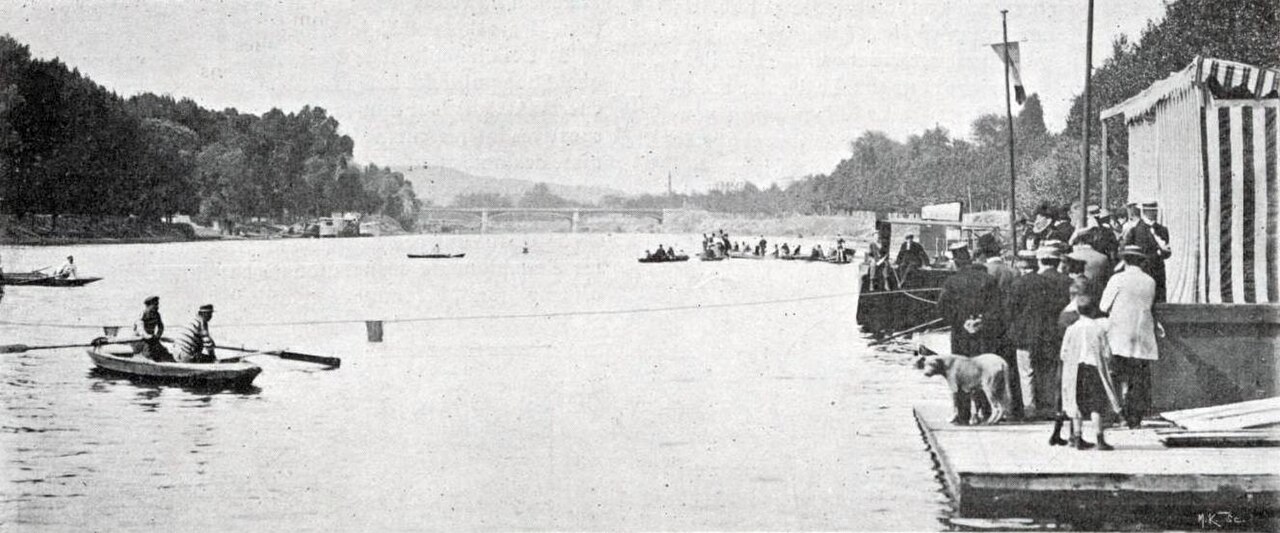

4. Obstacle Swimming 200 m (1900)

Swimmers in the Seine climbed over poles and boats, then ducked under more barriers before finishing 200 meters downstream. Currents and uneven lanes made times hard to compare. The format thrilled crowds once, but fairness and safety questions lingered. As modern pools standardized distance and timing, novelty river courses like this vanished from the Olympic schedule. Officials struggled to assign penalties for missed obstacles and tangles at bottlenecks. Pool meets with lane lines, starting blocks, and underwater rules created a clearer, repeatable product for athletes and fans.

5. Underwater Swimming (1900)

Athletes swam submerged in the Seine for up to one minute, scoring by distance and time spent underwater. Judges struggled to see competitors beneath murky water and spectators saw almost nothing. Visibility and safety concerns outweighed the spectacle. Pool-based events with electric timing replaced it as the program prioritized watchability and consistent, comparable results. Some competitors drifted with the current to maximize distance, undermining head to head racing drama. Dropping it opened room for sprints and relays that showcased speed.

6. Lacrosse (1904, 1908)

Field lacrosse appeared twice, with Canada winning gold both times. Early tournaments featured club squads and tiny brackets, not wide national participation. Travel costs and few European teams limited growth before World War I. Without a large, balanced field, the sport shifted to demonstration status and later thrived in world championships outside the Olympics. Medal rounds were thin, sometimes with only a handful of matches. Governance matured later, and modern world events now field dozens of nations, but early Olympic slots went to sports with deeper continents.

7. Polo (1900, 1908, 1920, 1924, 1936)

Mounted teams competed across sprawling fields, a spectacle requiring horses, grooms, and long travel for equine quarantine. Wealthy clubs dominated entries and logistics proved expensive for hosts. As television era planning began, the IOC favored compact venues and broader access. Polo left after 1936 because costs and limited global participation outweighed its prestige. Weather cancellations and uneven team access to quality horses affected fairness. As host cities sought inclusive participation, equestrian costs outside core disciplines became hard to justify on tight schedules.

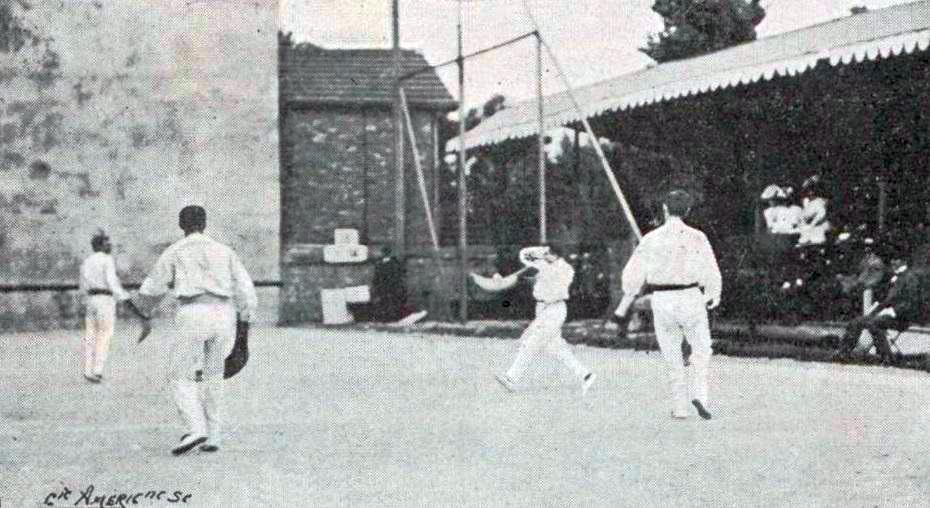

8. Cricket (1900)

Cricket’s sole Olympic appearance came in Paris with a two-day match between Great Britain and France. Scheduling issues and last-minute withdrawals collapsed a planned tournament. With few national teams and long match formats, the sport did not fit early Olympic timetables. Without broad reach then, cricket quietly exited the program for more universally played events. Match duration clashed with multi-sport programming and transport timetables. Efforts to revive the sport took shape decades later through independent tournaments as the Games emphasized shorter, broadcast-friendly formats.

9. Basque Pelota (1900)

Basque pelota, a lightning-fast wall game, featured briefly with variants like cesta punta. Entries were minimal and concentrated in Spain and France. Specialized courts and limited global player bases hindered repeat inclusion. Despite regional passion, the IOC prioritized sports with wider federations and easier venue replication across host cities. Hosts struggled to build regulation frontons near main stadiums. Demonstration events reappeared at later Games, but medal status required more nations, youth leagues, and standardized international calendars.

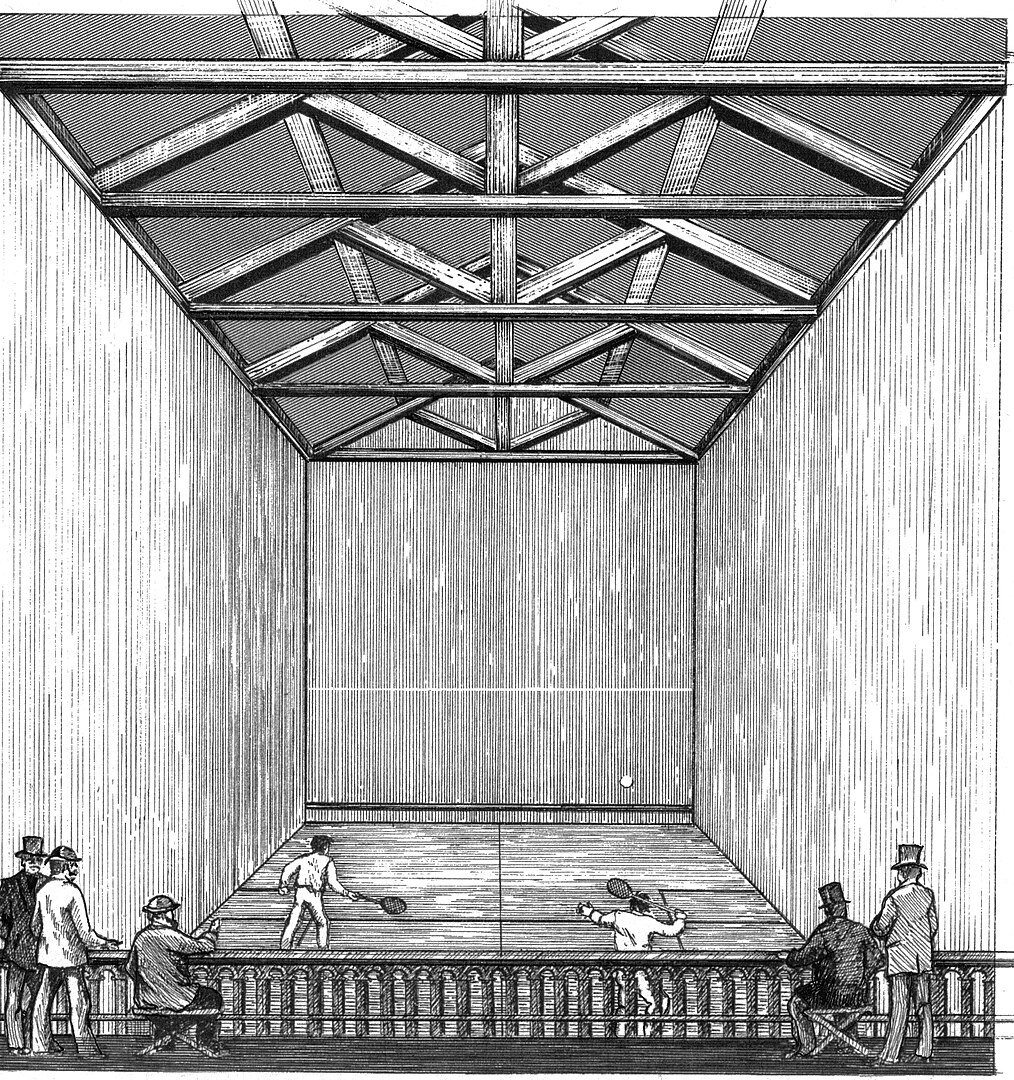

10. Rackets or Racquets (1908)

London 1908 staged rackets, the forerunner to modern squash, inside covered courts. Competition drew mostly British players and a narrow circle of Commonwealth talent. With few national bodies and expensive, specialized venues, the event lacked staying power. It vanished after one edition as the program shifted toward sports with broader international pipelines. Court availability outside Britain was sparse, and travel costs restricted entries. Squash later inherited momentum with a larger footprint, while rackets settled into niche clubs rather than Olympic arenas.

11. Field Handball, 11-a-side (1936)

Berlin 1936 introduced outdoor field handball with eleven players on soccer-sized pitches. Weather, space needs, and inconsistent playing styles proved problematic. Postwar, the indoor 7-a-side code grew under clear rules and compact arenas. Field handball disappeared, while the indoor version returned in 1972 and became a staple with global participation. Large grass pitches were hard to schedule amid football tournaments. The compact indoor variant fit winter seasons, TV sightlines, and urban venues, aligning better with the Games after the war.

12. Rope Climb in Gymnastics (1896-1932)

Men scaled a vertical rope for time and form, often starting from seated positions. Judging emphasized speed and a steady body, but apparatus standards varied by host. As artistic gymnastics focused on bars, rings, and floor, rope climb felt redundant. It ended after 1932 amid efforts to unify events under international scoring codes. Some nations used different rope lengths or knots, complicating comparisons. Streamlining the program kept events that displayed multiple apparatus skills rather than a single vertical sprint.