Every day life runs on ideas that many people never credit to women. This gallery pairs names with dates, patents, and clear outcomes, showing how paper bags, wipers, coffee filters, GPS, and even home security took shape. Each entry explains the problem they solved, when it appeared, and where you still see it today. You will find courtroom fights over stolen designs, lab breakthroughs that became global standards, and simple fixes that saved people steps at home. No fluff, just the chain from invention to daily use.

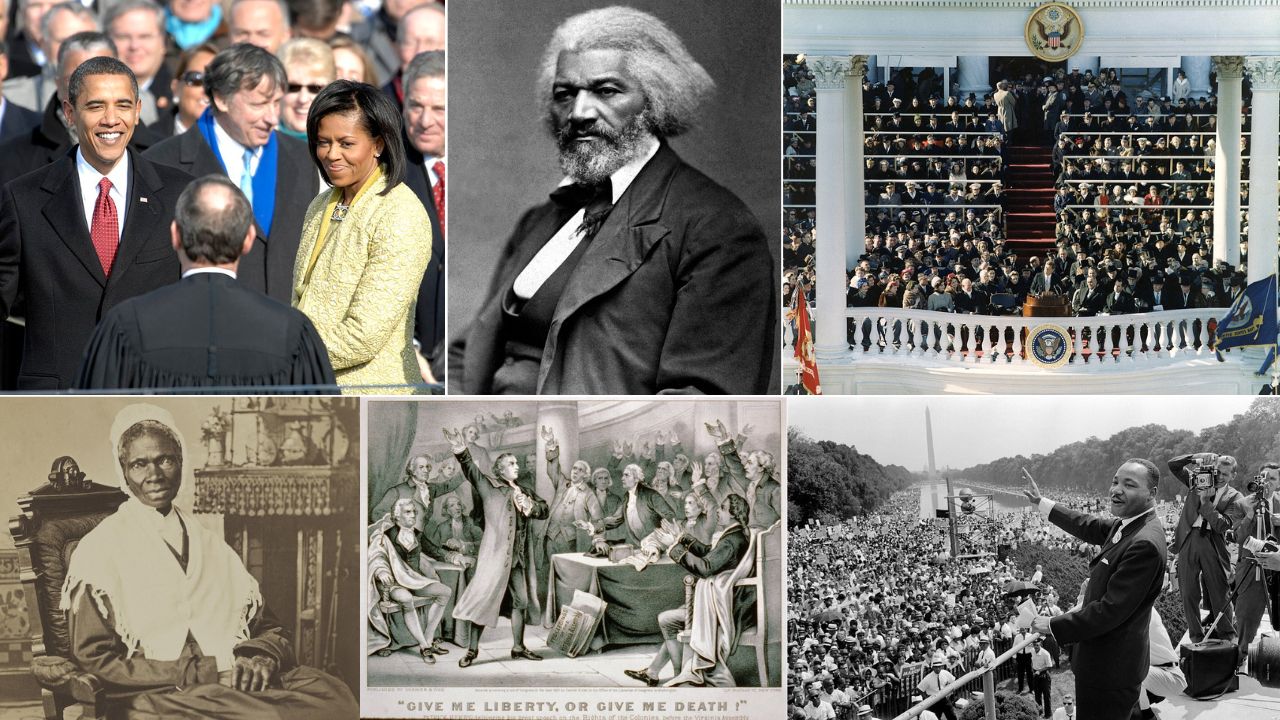

1. Margaret E. Knight

In 1871, Knight patented a machine that folded and glued flat-bottom paper bags, replacing hand work in mills. Steel dies, synchronized arms, and a creasing system produced sturdy sacks that stand while being filled. When a rival tried to claim her design, she won in court with working drawings and a wooden model. Stores could finally pack bulk goods at speed, and factories standardized sizes. Lunch bags and takeout sacks still use her format, proof that one shop floor fix reshaped retail.

2. Mary Anderson

Watching a streetcar stop so the driver could wipe sleet, Anderson sketched a cabin-controlled blade that swept glass without opening the window. Her 1903 patent described a spring-loaded arm with a rubber edge and a lever inside. Early drivers dismissed the device as a distraction, but faster cars and safety rules made clear sight essential. By the 1910s, wipers were routine on windshields. Today, every washer spray and intermittent swipe echoes that lever era solution to wet weather driving.

3. Melitta Bentz

In 1908, Melitta Bentz lined a perforated cup with blotting paper to filter bitter grit from percolators. She patented the paper filter and launched a company that refined cone shapes for even extraction. Clean taste, quick cleanup, and standardized sizes moved the design from a kitchen table idea to a daily brew method in homes and diners. Commercial drip brewers later scaled the concept for offices. The morning routine of placing a filter and pouring hot water follows her original plan.

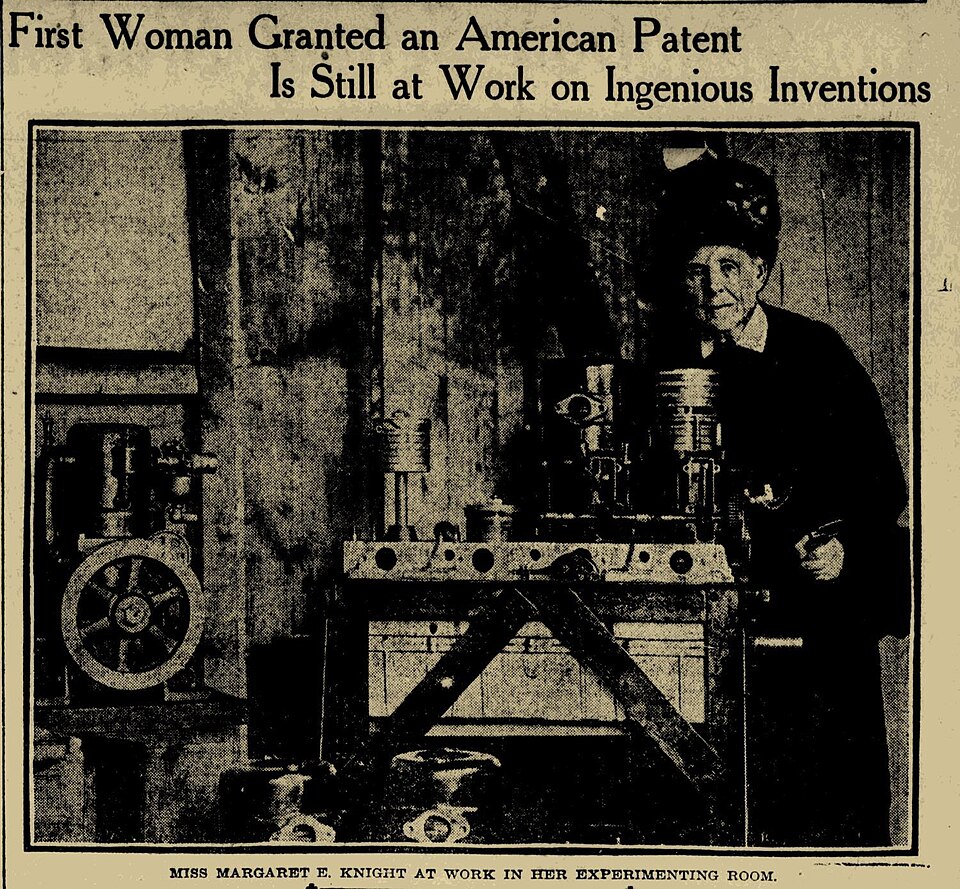

4. Lillian Moller Gilbreth

An engineer and psychologist, Gilbreth used time and motion study to cut wasted steps at home and in factories. In the 1920s and 1930s, she promoted refrigerator door shelves for quick reach, adjustable work heights, and the now common foot pedal trash can. Her data driven layouts influenced the kitchen work triangle and modern ergonomic checklists. The goal was simple: tools and storage where hands actually need them. Open a bin with your foot or grab milk from a door rack and you see her impact.

5. Sarah Boone

Boone’s 1892 patent improved ironing by adding a narrow, curved board that supported sleeves and fitted bodices without crushing seams. Hinges and padding let users pull garments over the taper and rotate smoothly to reach darts and cuffs. Earlier flat planks fought shaped clothing and left creases. Tailors still echo her idea with sleeve boards and pressing bucks. Foldable home boards that narrow at one end mirror Boone’s design, turning a frustrating job into clean lines with fewer scorch marks.

6. Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner

Kenner filed multiple practical patents, including a mid-1950s adjustable sanitary belt that secured pads before adhesive backs existed. She later patented a roll holder that kept the tissue end accessible and a back washer for tubs. Several firms rejected her early belt after learning she was Black, yet similar concepts spread as the market matured. Her designs focused on daily pain points and small hardware that anyone could use. Many modest bathroom conveniences trace to her insistence on simple, sturdy parts.

7. Josephine Cochrane

Tired of damaged china, Cochrane built wire racks and directed spray to wash dishes without breakage, then patented her machine in 1886. Hotels and restaurants bought early units because they delivered consistent cleaning between courses. The core remains today: custom racks, hot water, and targeted jets that separate delicate items. Her company later folded into brands behind KitchenAid, carrying the rack logic into homes. Open a modern dishwasher and you still see zones that protect plates, cups, and stemware like she planned.

8. Marie Van Brittan Brown

Working night shifts with slow police response, Brown filed in 1966 for a home system with a sliding camera, monitor, two-way audio, remote door unlock, and an alert button. The patent issued in 1969 and framed residential CCTV as a safety tool for families, not just businesses. Modern video doorbells and smart locks echo her feature list, from live views to callouts. By naming household risks and wiring a response path, she set expectations for integrated home security that remain standard.

9. Hedy Lamarr

During World War II, Lamarr co-invented a frequency hopping idea that jumped radio channels in sync to resist jamming. The 1942 patent anticipated spread-spectrum methods later adopted in secure communications. Wireless standards now use related techniques to share bandwidth and cut interference. When bluetooth earbuds hold a connection in a crowded building, they lean on the same principle. Lamarr’s sketchbook shows a movie star solving a hard engineering problem with timing and paired signals instead of brute force.

10. Gladys West

At a Navy lab from the late 1950s through the 1980s, West helped build precise models of Earth’s shape using satellite data. Correcting tiny bulges and dips produced a geoid that let receivers fix positions with far less error. That math underpins GPS, which now guides phones, ships, tractors, and delivery vans. Her work moved navigation from rough charts to lane-level routes. Each accurate driveway arrival comes from those equations that turned raw orbits into a reliable global reference.

11. Grace Hopper

Hopper proved software could be written in words people read, then compiled into machine instructions. In the 1950s, she built early compilers and later led work on COBOL, a language meant for business records and teams beyond engineers. Compilers unlocked larger programs, cleaner updates, and industries that could describe problems in plain syntax. Modern apps, from banking to games, rely on that translation step. Every build you install travels the path she mapped from human-friendly code to executable logic.

12. Bette Nesmith Graham

A typist facing retyping, Graham mixed tempera paint into a quick-drying correction fluid in the mid-1950s and sold it as Liquid Paper. Offices and schools used it to fix errors without feeding whole pages back into the carriage. Production scaled through the 1960s and 1970s, and the company sold in 1979, funding scholarships she created. Even now, variants sit in classrooms and studios for labels and forms. A small brush and a bottle turned mistakes into one-stroke fixes.