Stories about America’s Founding Fathers often sound polished and predictable. Textbooks and paintings smooth over quarrels, failures, and uneasy compromises until the revolution looks like a tidy plan carried out by men who always agreed. The real record is rougher and more interesting. Letters, drafts, and private complaints show doubts, grudges, and constant improvising. Seeing through the myths does not shrink their achievement. It turns distant icons back into people, which makes their choices more revealing and their legacy more honest.

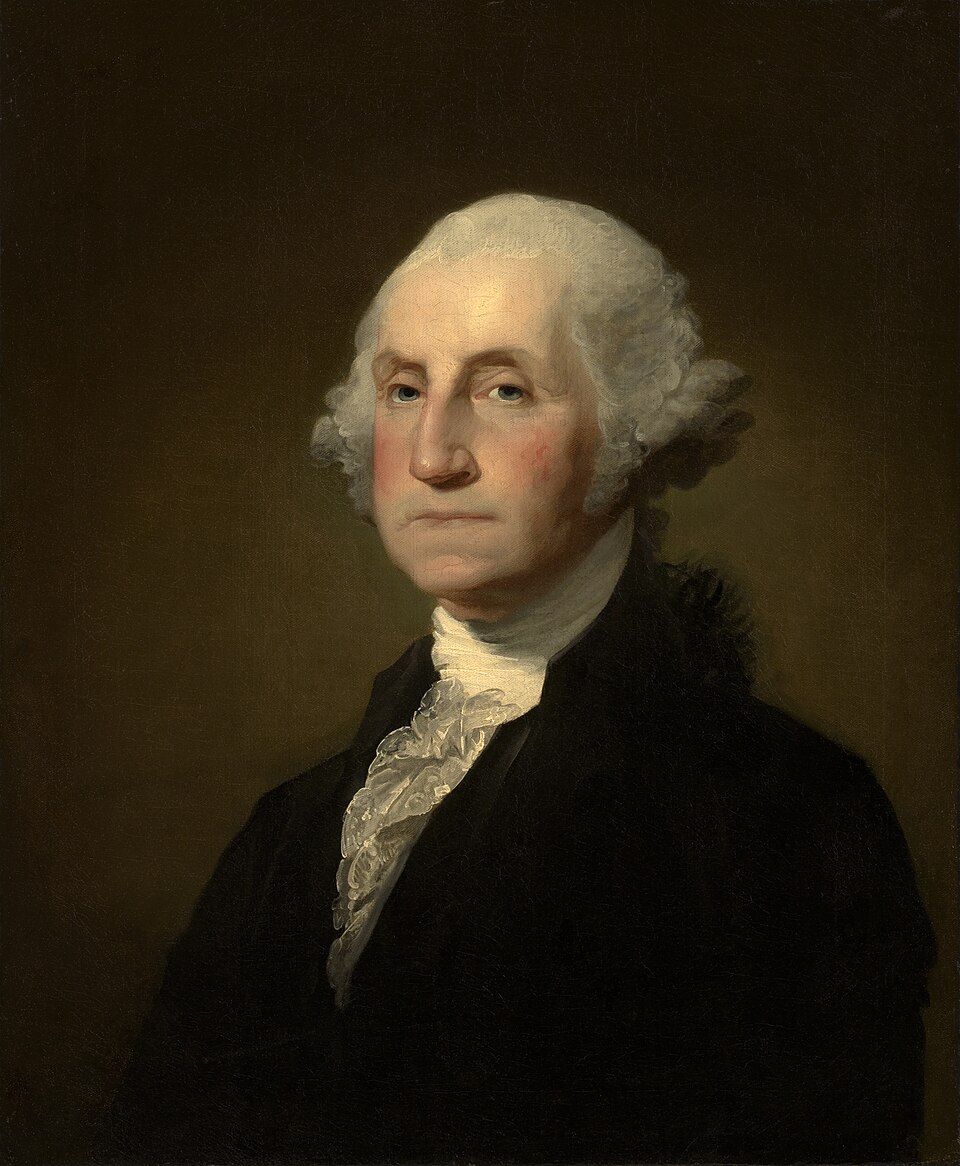

George Washington And The Cherry Tree

The famous cherry tree scene, where young Washington bravely admits what he did, is pure moral fable. It first appeared in a bestseller written years after his death, by a biographer who openly stitched in uplifting stories. No diary, family letter, or contemporary account mentions the incident. Historians treat it as a parlor tale that stuck because parents liked the lesson, not because it captures anything real about Washington’s childhood or character.

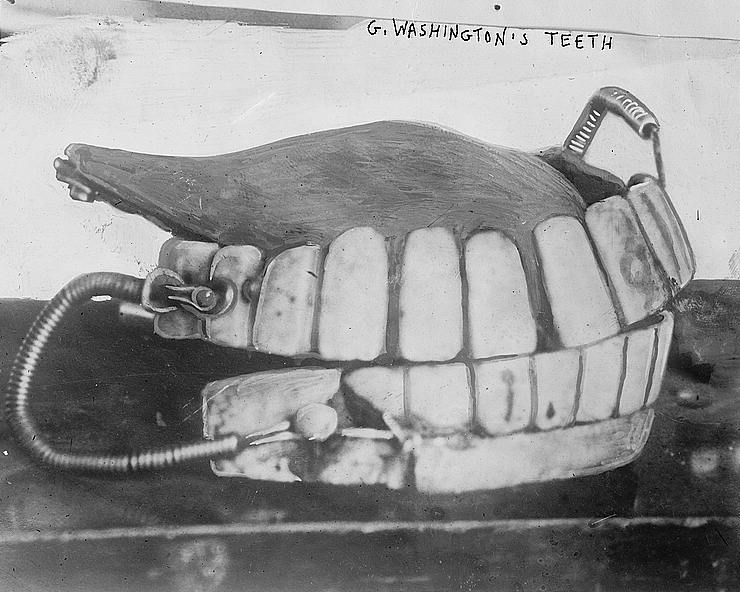

Washington’s Wooden Teeth

Washington’s dental misery was real, but his dentures were never carved from wood. Surviving sets show a harsh mix of human teeth bought from donors, animal teeth, ivory, and metal fittings that constantly needed adjustment. Over time, ivory stained and cracked, which probably looked like aged wood to observers. The truth is less charming than the myth, tying the first president’s smile to a trade in bodies and pain that sat in the background of elite eighteenth century life.

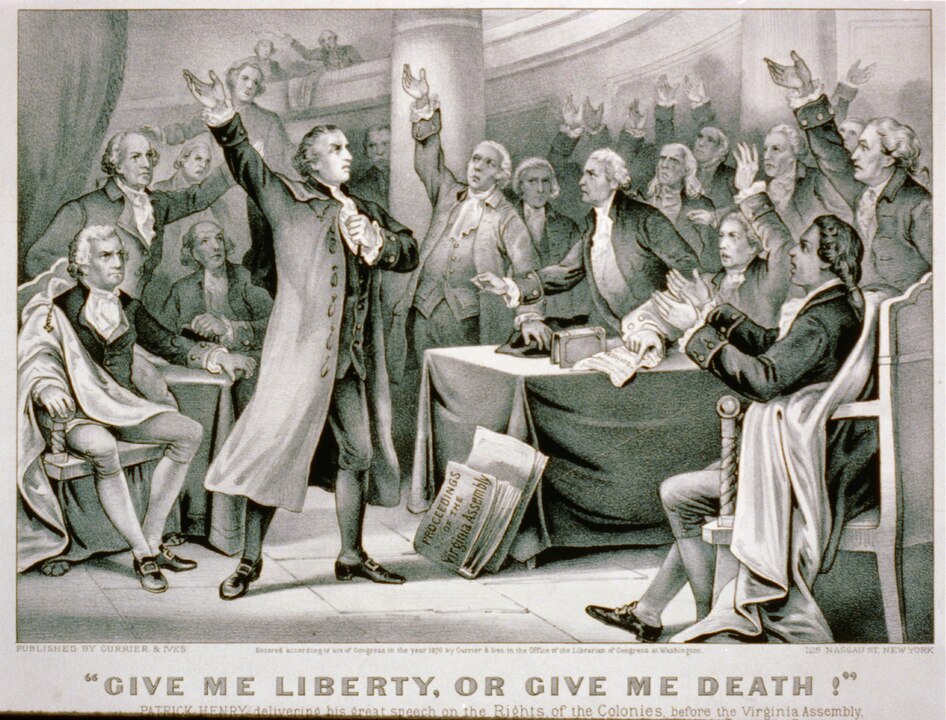

The Founders As One Unified Religious Group

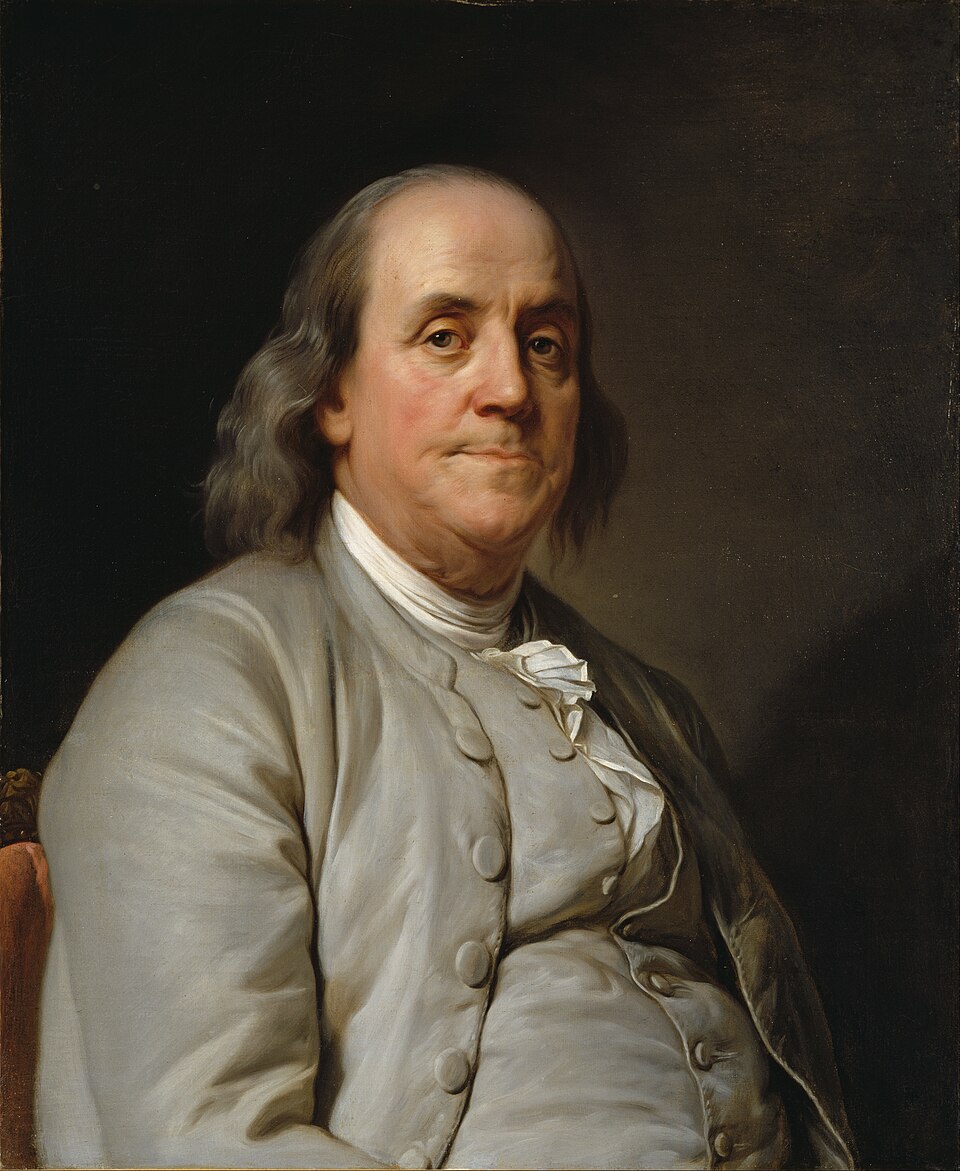

Founding era religion was crowded and complicated. Some leaders, like John Jay or Patrick Henry, fit easily into traditional church life. Others, including Jefferson and Franklin, leaned toward deism, favoring reason and natural law over miracles while still moving in Christian culture. Many supported strong protections for religious liberty and kept faith out of formal government. Treaties and public statements described the new republic in neutral terms, showing deep hesitation about fusing any single church with the state.

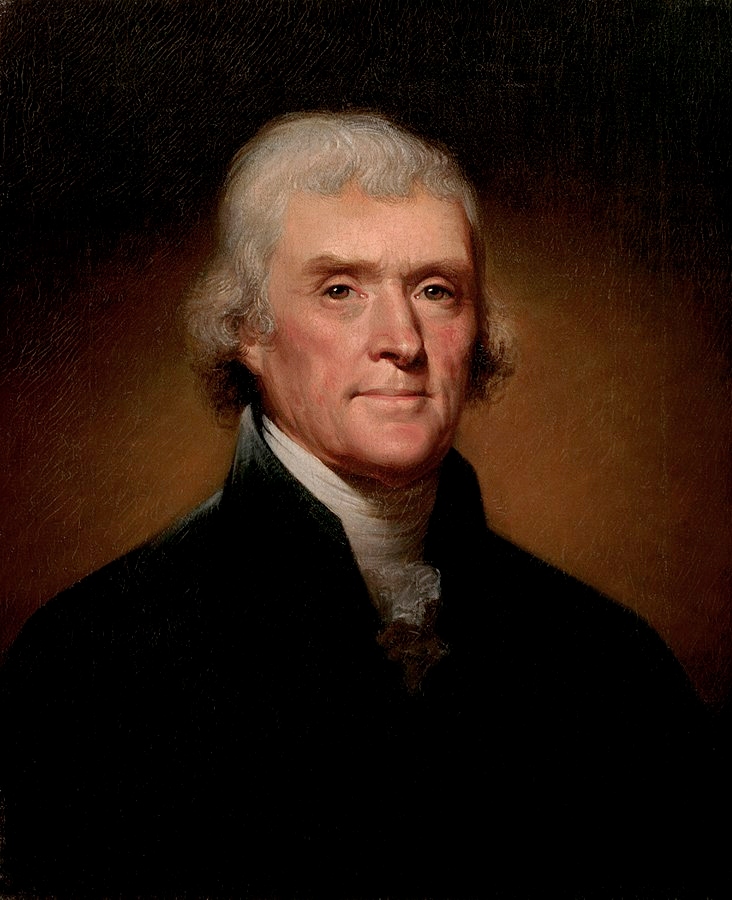

Jefferson As Sole Author Of The Declaration

Jefferson did draft the first version of the Declaration of Independence, but the words that survive are the product of many hands. The small drafting committee edited his language before it ever reached the full Continental Congress. Delegates then cut entire sections, altered phrases, and shifted tone to win broader support. Early drafts that still exist make the process easy to see on paper. The finished statement grew from clashing regional interests shaped into one voice, not from a lone genius.

Universal Support For Independence

Later retellings often make independence feel like destiny, as if everyone marched toward July 1776 with full conviction. Letters from the period sound very different. Many colonists still hoped for compromise within the British Empire and feared that a break would bring ruin. Loyalists saw the rebels as reckless adventurers inviting chaos. Even in Congress, leaders hesitated and counted votes before moving. Independence came out of a hard fought political decision, not a unanimous rush into freedom.

All Founders As Slaveholders

Slavery sat at the center of the new nation, but the founders’ personal roles in it varied. Plantation owners in Virginia and other southern colonies enslaved hundreds of people and built fortunes on their labor. Some northern leaders, including John Adams and a number of New Englanders, never owned slaves and backed gradual abolition. Others freed enslaved people late in life or only on paper. The generation was not united; arguments over slavery were already tearing at the political fabric.

Jefferson And The Constitution

Jefferson’s name is so tightly linked with founding ideals that many assume he helped write and sign the Constitution. In 1787, he was serving abroad as minister to France, sending letters but not sitting in the Philadelphia hall. John Adams was also overseas. Only a small group signed both the Declaration and the Constitution. Different factions, problems, and compromises defined each document. Treating Jefferson as architect of both blurs the fact that the founding unfolded in stages, not in one moment.

Benjamin Franklin And The Turkey

The story of Franklin fighting for the turkey as a national emblem begins with a private joke. In a letter to his daughter, he poked fun at an early eagle design and half seriously praised the turkey as more respectable than a lazy bird of prey. That bit of family humor was later lifted out of context and retold as public policy. There is no evidence that Congress ever came close to placing a strutting turkey on official seals.

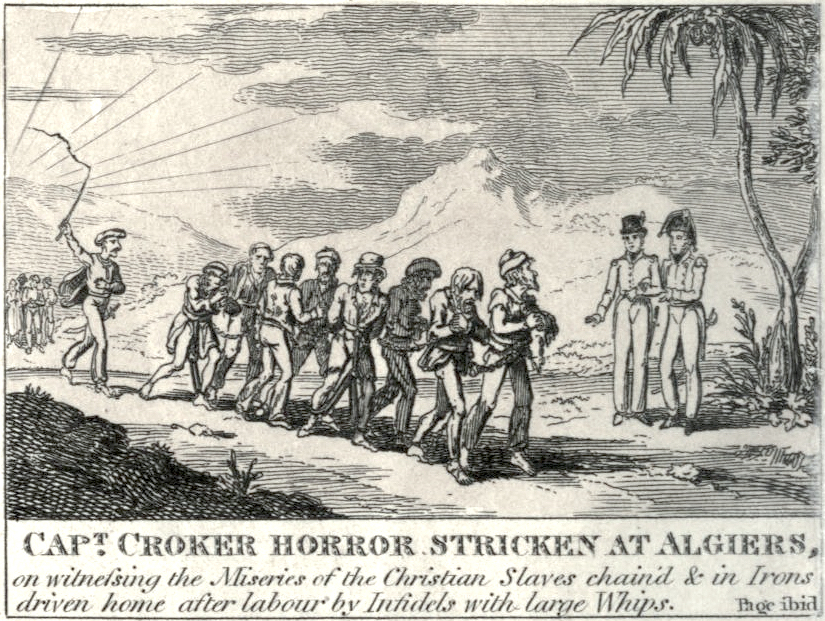

Elderly Men In Wigs

Paintings and schoolroom posters often show a room filled with gray hair and stiff formal wear, but many leading figures were surprisingly young. Hamilton was barely into his twenties when he rose in revolutionary circles. Madison and Monroe were also in their twenties as events accelerated. Even at the Constitutional Convention, the typical delegate was in his forties, not an old man at the end of life. The revolution was driven by a mix of rising youth and seasoned elders.

No Indigenous Influence

For a long time, popular stories treated the founders as drawing only from Europe. In reality, many of them met with Native diplomats, studied Indigenous alliances, and saw how confederacies could bind distinct nations. The Haudenosaunee system, in particular, offered a working example of shared councils and layered authority. Scholars still debate exactly how far that influence traveled into American structures, but ignoring Indigenous models erases voices that the founders themselves watched closely and sometimes admired in private notes.

A Finished And Perfect Democracy

Civic speeches sometimes describe the founding moment as the creation of a flawless plan that only needed faithful obedience. The founders rarely spoke in such confident tones. Many called the Constitution an experiment and expected later generations to amend and improve it. They knew that serious injustices, especially slavery and narrow voting rules, remained in place. Later struggles for civil rights and representation did not betray a perfect design; they carried forward work the original architects left unfinished.