Forced relocations reshaped Native American life for centuries. Laws like the Indian Removal Act of 1830, military campaigns, allotment under the Dawes Act, and later federal relocation programs pushed communities from their homelands, broke economies, and strained cultures. Yet nations rebuilt governments, schools, and ceremonies in new places. This gallery highlights eleven pivotal removals across regions and eras, explaining what happened, why it happened, and how Native peoples endured. Knowing these stories helps teens read U.S. history with clarity and empathy.

1. Trail of Tears – Cherokee Removal (1838–1839)

Under the Indian Removal Act, U.S. troops forced about 16,000 Cherokee from Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, and North Carolina to Indian Territory. Families were held in stockades, then made to travel more than a thousand miles by foot and by wagon. Disease, winter exposure, and hunger killed an estimated 4,000 people. Despite the Supreme Court’s Worcester v. Georgia decision affirming tribal sovereignty, removal proceeded. In Oklahoma, the Cherokee rebuilt a constitutional government and schools, showing resilience after state and federal pressure.

2. Choctaw Removal (1831–1833)

The Choctaw were the first large nation removed under the 1830 law, ceding millions of acres in the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. Thousands moved west along winter routes to Indian Territory, many without adequate clothing or supplies. Reports described frostbite, illness, and deaths along rivers and muddy roads. The ordeal set a template for later removals. In present-day Oklahoma, the Choctaw re-established governance, invested in education, and adapted their economy, even as the loss of Mississippi homelands remained a lasting wound.

3. Chickasaw Removal (1837)

After years of pressure and broken promises, the Chickasaw agreed to move west and purchase land within the Choctaw domain. The 1837 migration involved difficult river crossings and overland trails where disease spread quickly. Many travelers died, and families sold property at unfair prices to finance the journey. In Indian Territory, the Chickasaw formed a separate government, protected communal interests, and later supported schools. The removal shows how negotiations under duress produced costly outcomes that tribes then had to transform into new beginnings.

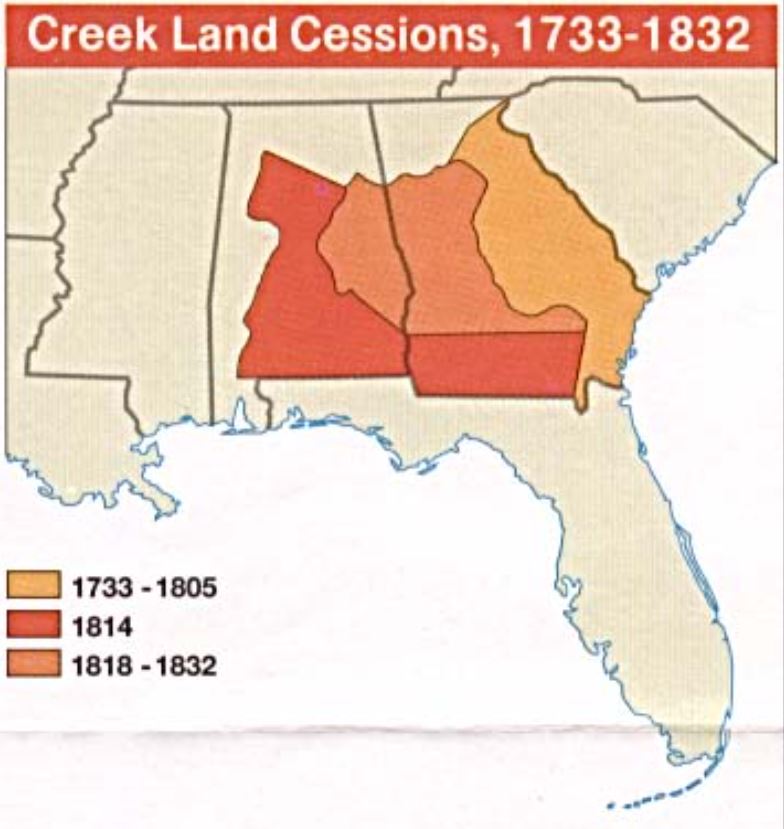

4. Creek – Muscogee Removal (1830s)

Following conflicts and coerced treaties, the Muscogee lost vast areas in Alabama and Georgia. Thousands were marched in detachments to Indian Territory, and some captives were transported in chains. Historians estimate the Muscogee lost around 22 million acres, dismantling towns and trade networks. Along the routes, shortages, dysentery, and exposure took lives. In Oklahoma, the Muscogee Nation reconstructed towns and a national council, preserving language and ceremonial life while navigating federal agents, missionaries, and the pressures of frontier settlement.

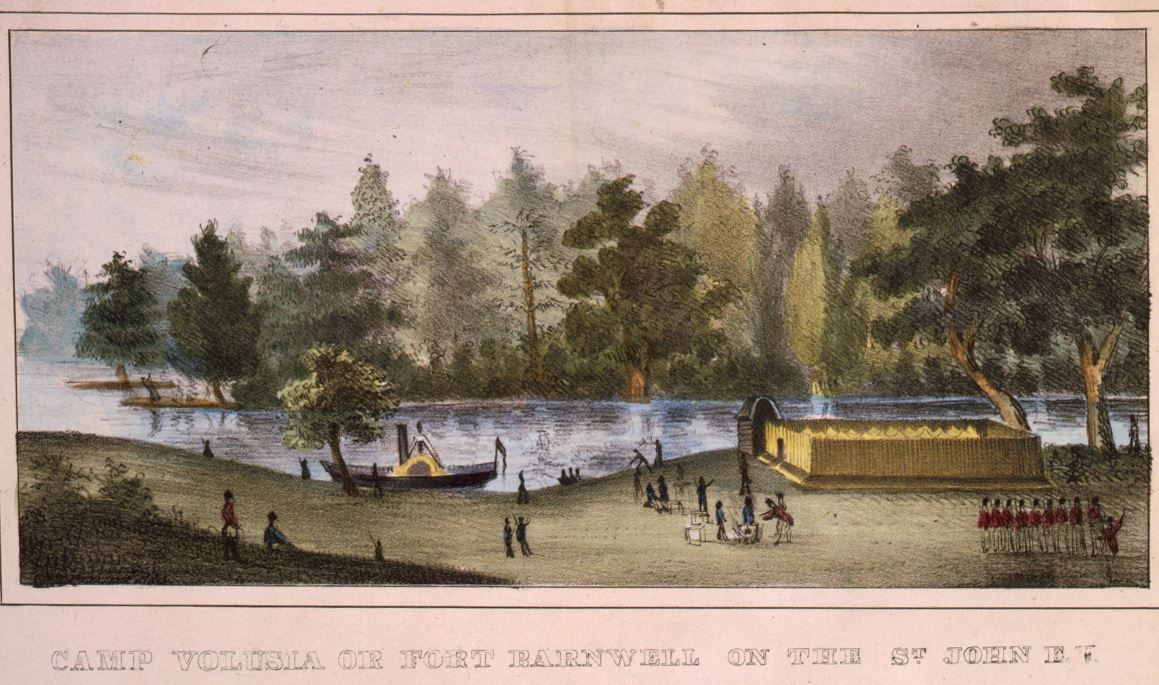

5. Seminole Removal and Resistance (1830s–1840s)

Federal efforts to remove the Seminole from Florida sparked the Second Seminole War, a seven-year conflict in swamps and hammocks. Some Seminoles, allied with freedom seekers fleeing slavery, resisted with guerrilla tactics. Others were captured and shipped west by steamer. The fighting, disease, and family separations were devastating, yet a portion of the Seminole remained in Florida’s remote areas, ancestors of today’s Seminole and Miccosukee. In Indian Territory, removed Seminoles reorganized their government while remembering the cost of resistance and exile.

6. Long Walk of the Navajo – Diné (1864)

After a scorched-earth campaign that destroyed crops and sheep, roughly 8,500 Diné were forced to march 300 to 400 miles to Bosque Redondo in New Mexico Territory. The reservation’s soil and water were poor, and rations were unreliable, leading to hunger and disease. Hundreds died on the routes and at the site. In 1868, the Treaty of Bosque Redondo allowed the Diné to return to a portion of their homeland. Rebuilding herds, governance, and weaving economies became acts of survival and renewal.

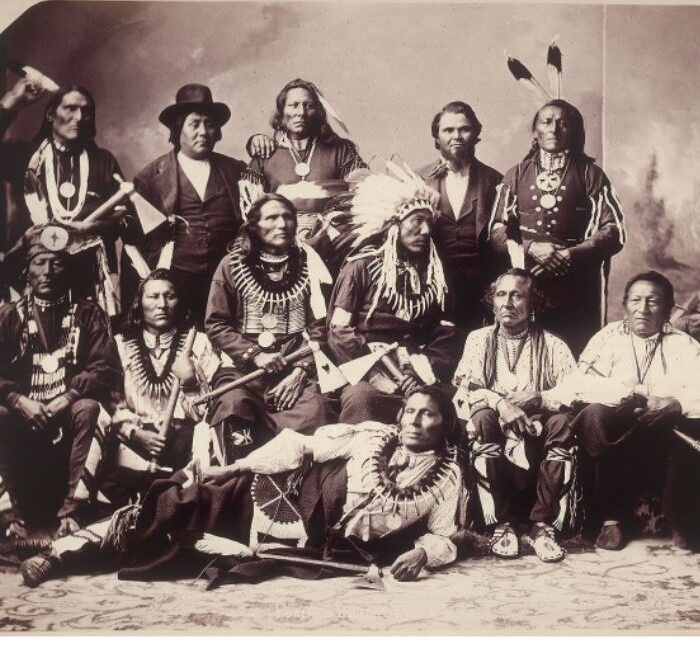

7. Ponca Trail of Tears (1877)

A mapping and treaty error placed the Ponca on land assigned to another nation, exposing them to attacks. Federal officials then ordered their removal from Nebraska to Indian Territory. The 600-mile trek involved floods, harsh weather, and limited supplies; children and elders died along the way. The death of Chief Standing Bear’s son helped spark a landmark 1879 court ruling recognizing that Native people are “persons” under U.S. law. The case linked removal-era suffering to foundational civil rights principles.

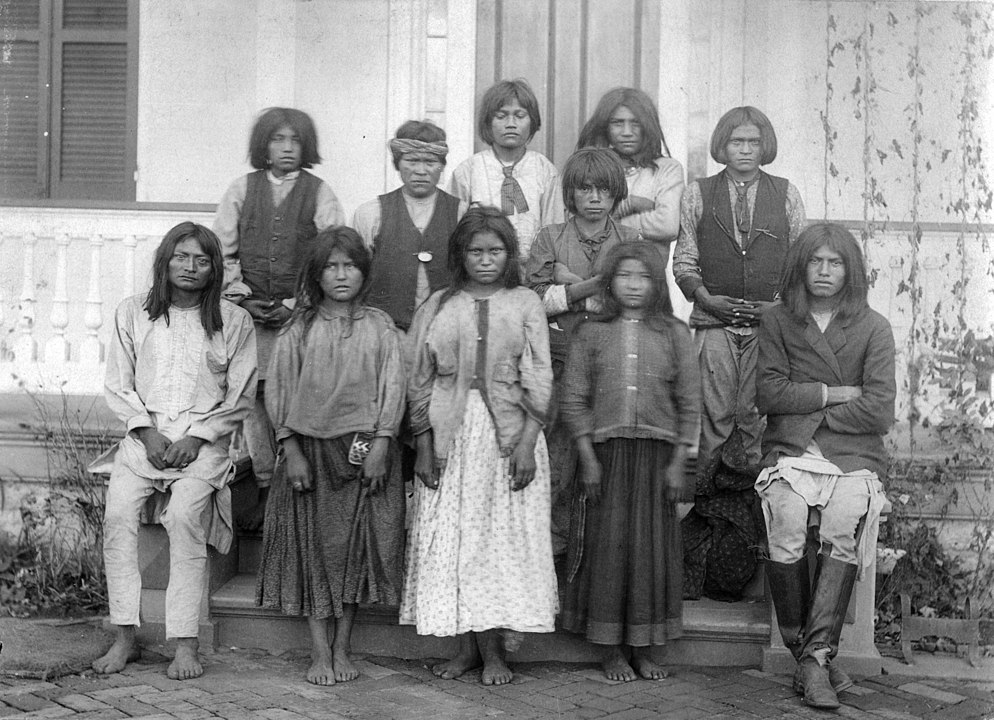

8. Chiricahua Apache Exile (1876–1885 and after)

Pressure for land and conflict on the Arizona frontier led officials to dismantle Chiricahua reservations. Bands under leaders including Geronimo fled into Mexico, then surrendered amid relentless pursuit. Instead of relocation to nearby lands, hundreds of Chiricahua men, women, and children were shipped as prisoners of war to Florida, Alabama, and Oklahoma for decades. Families were separated, and leaders died far from home. Eventually, many resettled near the Mescalero Apache, carrying memories of exile and extraordinary endurance.

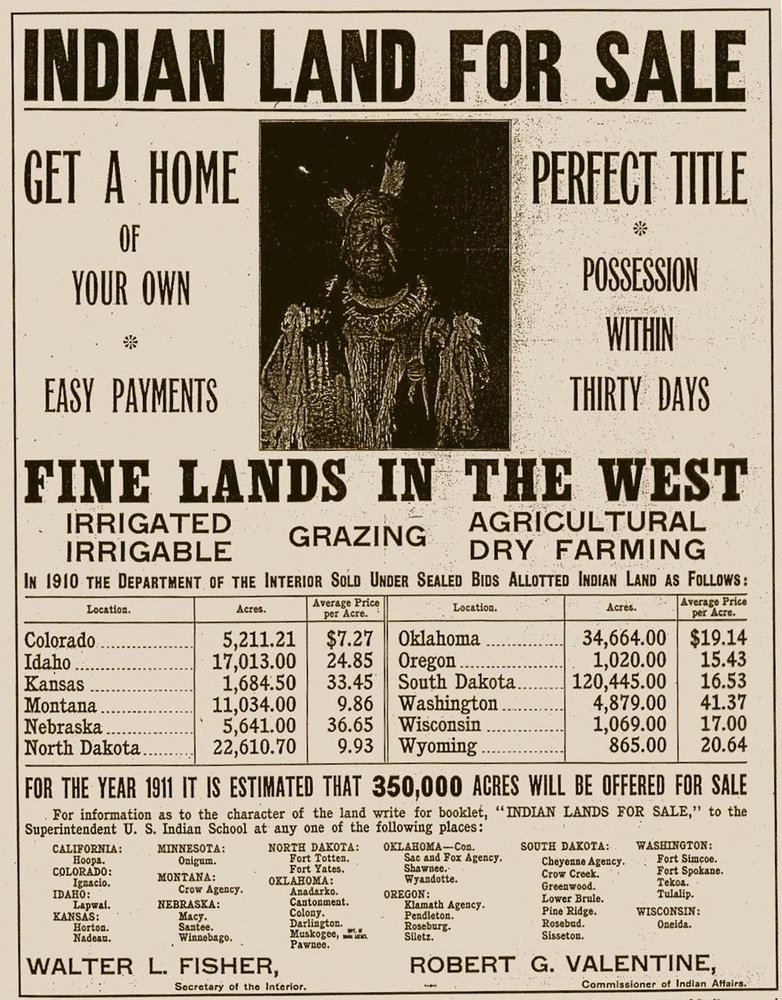

9. Dawes Act Allotment and Dispossession (1887–1934)

The Dawes General Allotment Act broke up communal lands into individual parcels, framing allotment as a path to citizenship and farming. “Surplus” lands were opened to non-Native buyers, while many Native families lost allotments to taxes, debt, or fraud. By 1934, tribal landholdings had fallen by nearly two-thirds. Although not a single march, allotment forced relocations within and beyond reservations, fractured extended families, and undercut tribal governance. The Indian Reorganization Act later halted allotment and encouraged self-government.

10. Urban Relocation Program (1950s–1970s)

The Bureau of Indian Affairs promoted “voluntary” moves from reservations to cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, and Denver with promises of jobs and training. Relocatees often faced high rents, discrimination, and limited services, leading to hardship and cultural disconnection. Yet urban Native communities grew, forming centers, churches, and advocacy groups. The program fit a wider federal push to terminate reservations and reduce federal obligations. Teens can see both loss and creativity here: new networks emerged under difficult, assimilationist policies.

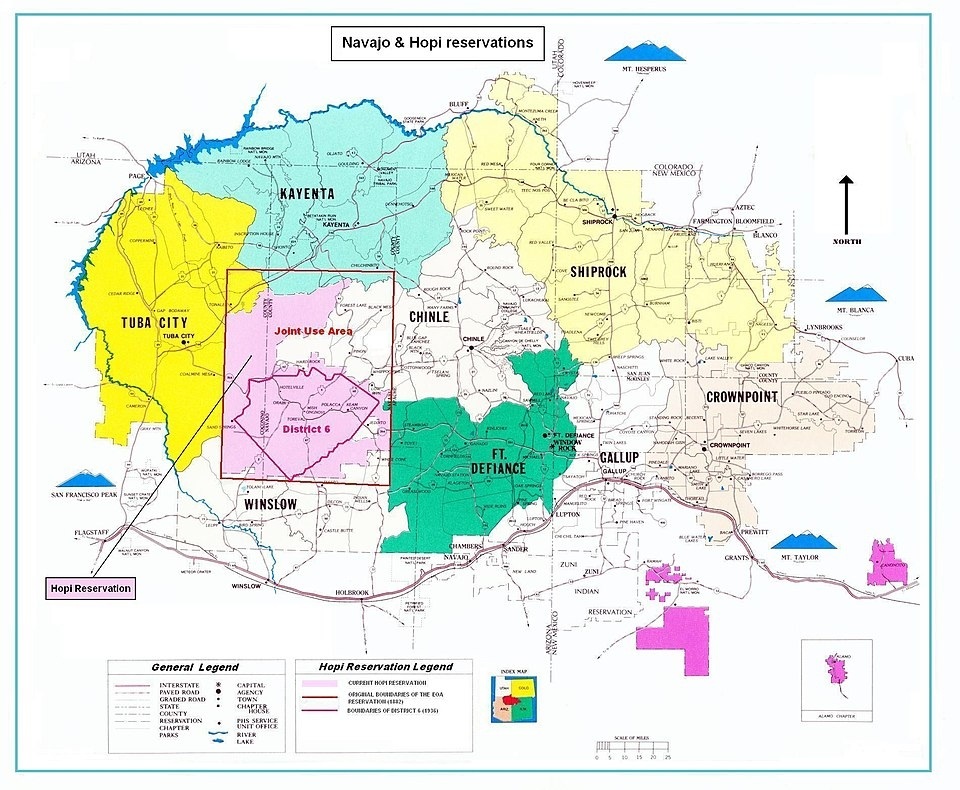

11. Navajo–Hopi Land Dispute Relocation (1974)

Congress passed the Navajo-Hopi Land Settlement Act dividing 1.8 million acres of jointly used land. Thousands of Navajo who found themselves on the Hopi Partitioned Lands were ordered to move, even when their families had herded sheep there for generations. Compensation and new houses could not replace sacred places or grazing systems. The relocation deepened tensions and trauma while court cases and mediation continued for years. The episode shows how boundary lines on paper can unsettle living cultures on the ground.