Big names like Yellowstone and Chichén Itzá get the hype, but quieter UNESCO sites across North America hold rare stories, fossils, and ancient engineering. These places protect coral reefs, desert roads, Arctic-born caribou routes, and earthworks older than the Roman Republic. You’ll see inscription years, exact locations, and simple rules to keep visits safe. Bring water, respect closures, and stay on signed paths to prevent erosion. Many sites restrict drones, require guided access, or close fragile areas during storms or high tides. Check local advisories a day before you go, print a paper map where service drops, and pack layers. With smart planning, you can explore deep history without crowds, then head home with facts you can actually pin to dates, distances, and maps.

1. Poverty Point (Louisiana, USA)

This earthwork city rose around 1700–1100 BCE on the lower Mississippi. Six C-shaped ridges, a grand plaza, and a 72-foot mound form a planned layout visible today. UNESCO inscribed it in 2014 for engineering and continent-wide trade, including stone tools traced hundreds of miles. Trails are mostly level but sunny; summer heat and insects are real. Stay on mown paths to protect fragile soils, and skip ridge climbing where signs forbid it. The museum explains how archaeologists date the ridges, and rangers run short walks that highlight drainage design after heavy rain.

2. Chaco Culture (New Mexico, USA)

Chaco Canyon holds great houses like Pueblo Bonito built 850–1250 CE with millions of sandstone blocks and timber hauled from distant mountains. Straight ceremonial roads run for miles across the desert. Inscribed in 1987, the park protects dark skies, so headlights are limited at night and astronomy programs run on clear dates. Summer monsoons can flood dirt spurs off US-550; check road status before committing. Bring at least 1 gallon of water per person and sun protection. Drones are banned, and several backcountry trails require registering at trailheads.

3. Cahokia Mounds (Illinois, USA)

Across the Mississippi from St. Louis, Cahokia peaked around 1050–1200 CE with more than 100 mounds. Monks Mound rises about 100 feet and spans 14 acres, the largest earthwork in North America. UNESCO listed it in 1982 for urban planning and astronomy; a wooden “Woodhenge” circle marks solstices. Stay off closed slopes to prevent erosion, and use stairs provided. The interpretive center (hours vary by season) shows copper, shell, and chert trade goods linking the Plains, Gulf, and Great Lakes. Winter visits offer quiet trails and wide views of the American Bottom.

4. Papahānaumokuākea (Hawaii, USA)

This vast marine monument, inscribed in 2010 and expanded in 2016, stretches over 1,500 miles across the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. It protects coral reefs, Hawaiian monk seals, green sea turtles, and millions of nesting seabirds. Access is tightly controlled; most visitors learn through exhibits on Oʻahu or permitted Midway tours. Use reef-safe, mineral sunscreen and respect posted wildlife distances in feet. Storm systems can form quickly over the Pacific, changing flight or boat plans. Cultural briefings explain Native Hawaiian stewardship and why some islands remain kapu, or off-limits, to general tourism.

5. Mistaken Point (Newfoundland, Canada)

Wave-washed rock slabs here preserve Ediacaran fossils from roughly 565–560 million years ago, some of the oldest complex life on Earth. UNESCO listed the site in 2016 for its exceptional bedding planes covered in soft-bodied impressions. Access is by guided hike only to prevent damage. Fog rolls off the Atlantic in minutes, and winds can exceed 30 mph, so bring layers and boots with grip. Guides time visits to low tide so surfaces are visible and safe to cross. No casting or touching is allowed; photography is fine under staff direction.

6. Joggins Fossil Cliffs (Nova Scotia, Canada)

These Bay of Fundy cliffs reveal a 300-million-year-old coal forest with upright fossil trees frozen in place. Inscribed in 2008, Joggins features the world’s highest tides, rising and falling up to 50 feet. That tidal swing uncovers new finds but can cut off beach exits fast. Check tide tables, join guided walks, and keep hands off exposed fossils unless staff invites supervised study. The center’s exhibits show how layers stack like pages and how trackways record ancient amphibians. Bring a wind jacket; sea breezes make summer feel cooler than inland towns.

7. Gros Morne National Park (Newfoundland, Canada)

Gros Morne, listed in 1987, lifts pieces of Earth’s mantle to the surface at the Tablelands, where orange peridotite soils limit plant life. Elsewhere, fjords, tuckamore forests, and caribou define the landscape. Trails range from boardwalks to steep scrambles like Gros Morne Mountain. Weather flips quickly; ridge winds near 40 mph are common, and fog can drop visibility to yards. Stay on marked routes to protect fragile geology, and pack bear-safe food storage for backcountry camps. Boat tours run seasonally on Western Brook Pond.

8. Sian Ka’an (Quintana Roo, Mexico)

This 1.3-million-acre reserve, inscribed in 1987, mixes mangroves, coastal lagoons, tropical forest, and reef. Boardwalks and boat tours follow marked channels to protect manatees, crocodiles, and wading birds. Bring cash for community launches, wear life jackets, and use mineral sunscreen to protect corals. June–November is storm season; sandy access roads can flood after heavy rain. Respect archaeological areas and no-take zones. Early mornings deliver quieter wildlife sightings, while afternoon sea breezes make the heat more manageable.

9. Rock Paintings of the Sierra de San Francisco (Baja California Sur, Mexico)

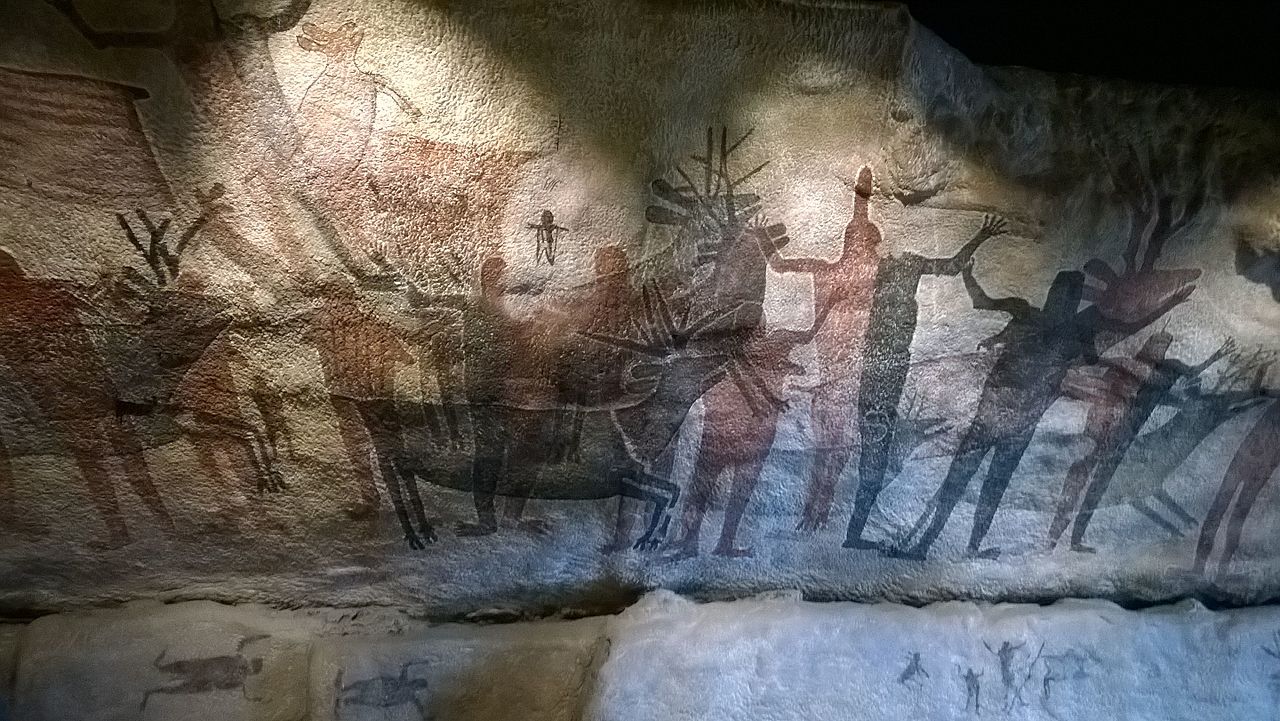

Cave murals painted roughly 100 BCE to 1300 CE show humans, deer, rabbits, and whales in bold reds and blacks across remote canyons. UNESCO inscribed the region in 1993. Access often requires mule treks with licensed guides and permits, which helps limit impact. Daytime highs can top 90°F in spring; nights turn cool. Pack at least 3 liters of water per person, a brimmed hat, and sun sleeves. Touching panels is prohibited; photos are fine without flash. Trails are rocky, so bring sturdy shoes with tread.

10. Pimachiowin Aki (Manitoba/Ontario, Canada)

Listed in 2018, this 11,000-square-mile boreal forest and water route is a living cultural landscape of Anishinaabe communities. Wild rice beds, pictographs, and ancient portages link lakes and rivers used for generations. Canoeists follow community guidance, carry bear-safe food barrels, and respect closures for fires or nesting. Mosquitoes peak in June, so nets and long sleeves help. Winter travel uses marked ice roads set by local authorities. Leave no trace on campsites, and give loons and eagles wide space measured in boat lengths.