Not every breakthrough starts with a plan. Sometimes science moves forward because someone notices something weird and refuses to ignore it. A mold that kills bacteria, a glowing screen across the room, a radio hiss that will not go away, a candy bar that melts near a machine, each mistake or surprise led to a discovery. These ten accidents are backed by dates, names, and real-world impacts, showing how curiosity turns slipups into progress that helps hospitals, classrooms, and even your kitchen.

1. Penicillin, 1928

Bacteriologist Alexander Fleming returned to his London lab and found a mold contaminating a Petri dish of staph. Around the mold, the bacteria were dead. He identified the mold as Penicillium and published the finding in 1929. A decade later, Howard Florey, Ernst Chain, and team turned that lab clue into a usable drug. By World War II, penicillin was saving lives from sepsis and pneumonia. It launched the antibiotic era, driving hospital death rates down and changing standard care across the world.

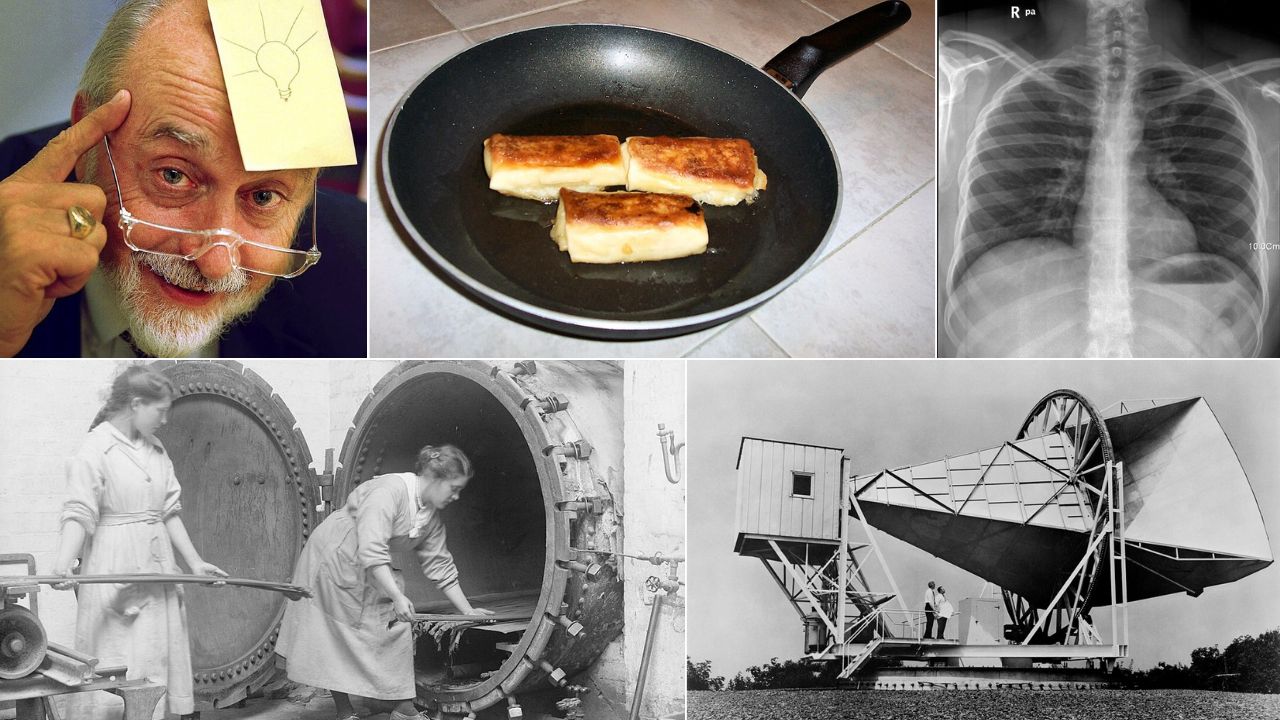

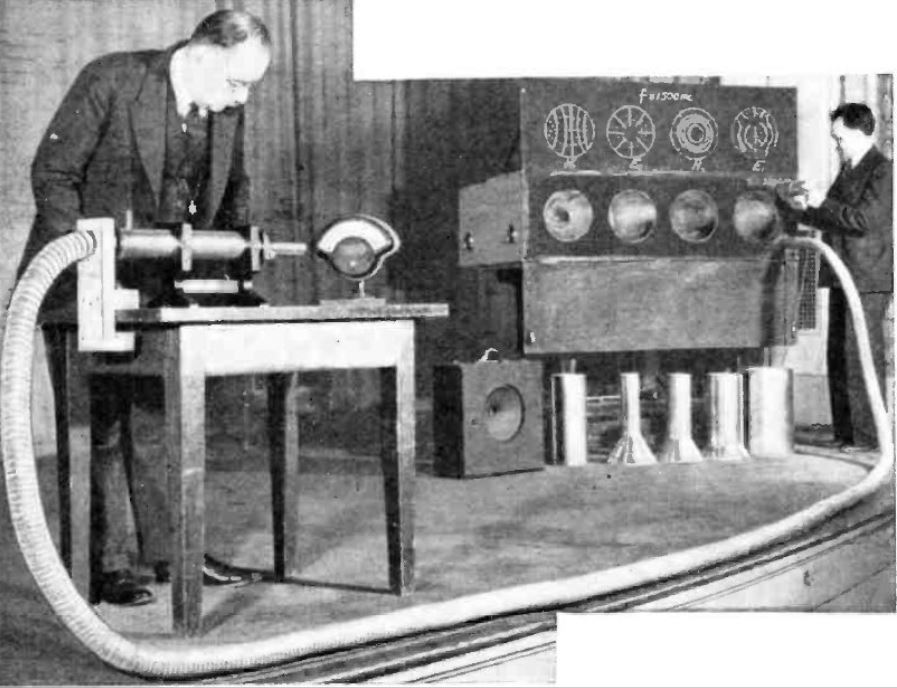

2. X-Rays, 1895

While testing cathode-ray tubes in a dark room, Wilhelm Röntgen noticed a nearby fluorescent screen glowing even though the tube was covered. He realized unknown rays were passing through materials and called them X-rays. Within weeks, doctors used the effect to image broken bones and bullets. The first medical X-ray images date to 1895–1896. Physics followed, linking X-rays to very short-wavelength electromagnetic waves. The surprise created radiology, now used in clinics, airports, and research labs for noninvasive views inside solid objects.

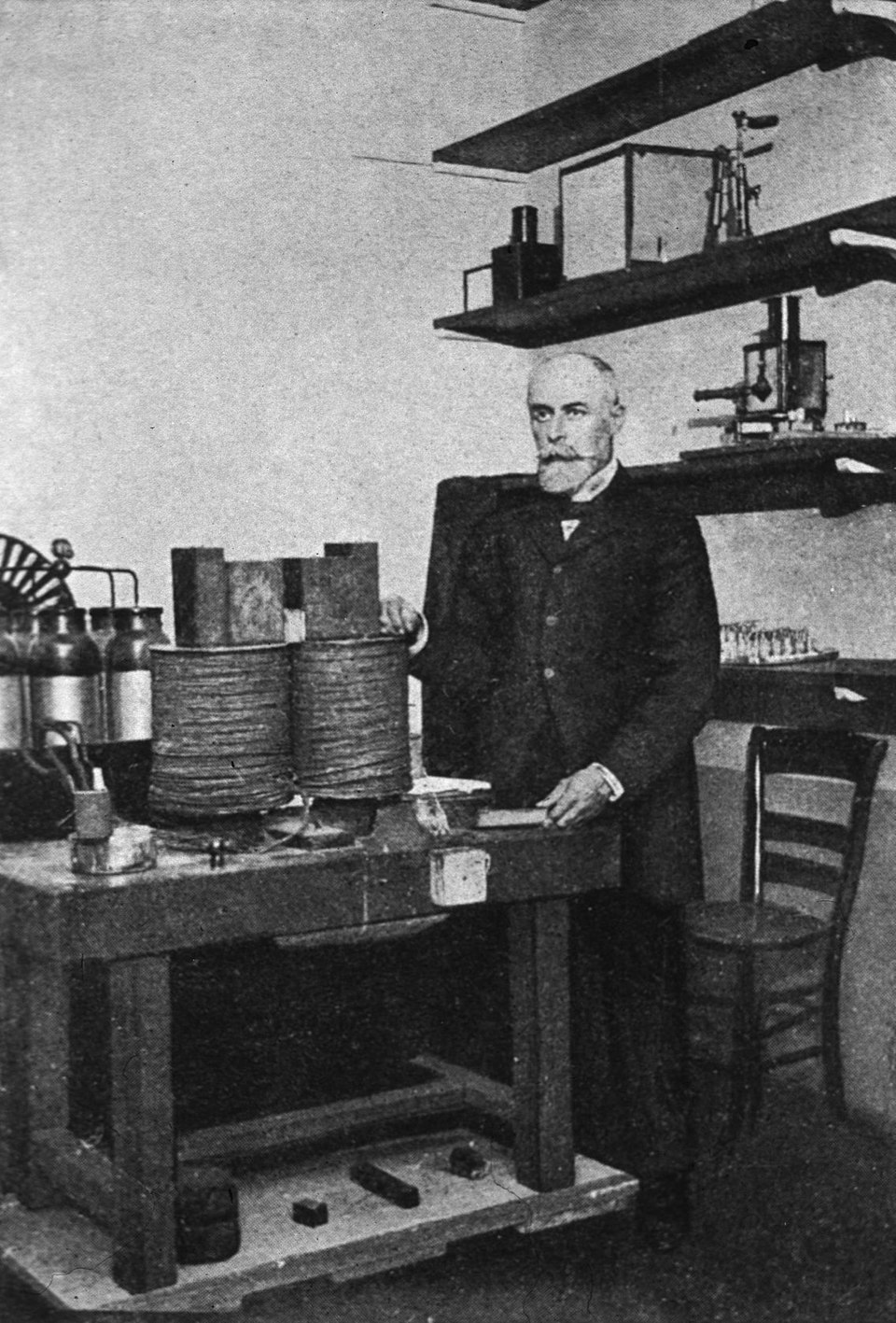

3. Radioactivity, 1896

Henri Becquerel stored uranium salts with wrapped photographic plates while studying phosphorescence. Even without sunlight, the plates fogged. That meant the salts emitted their own penetrating energy. Marie and Pierre Curie soon isolated new radioactive elements, including radium and polonium, and the field of nuclear physics was born. The accidental plate marks led to cancer therapies, power research, and strict safety rules. The key lesson was simple, unexplained evidence matters, even if it first looks like ruined lab film.

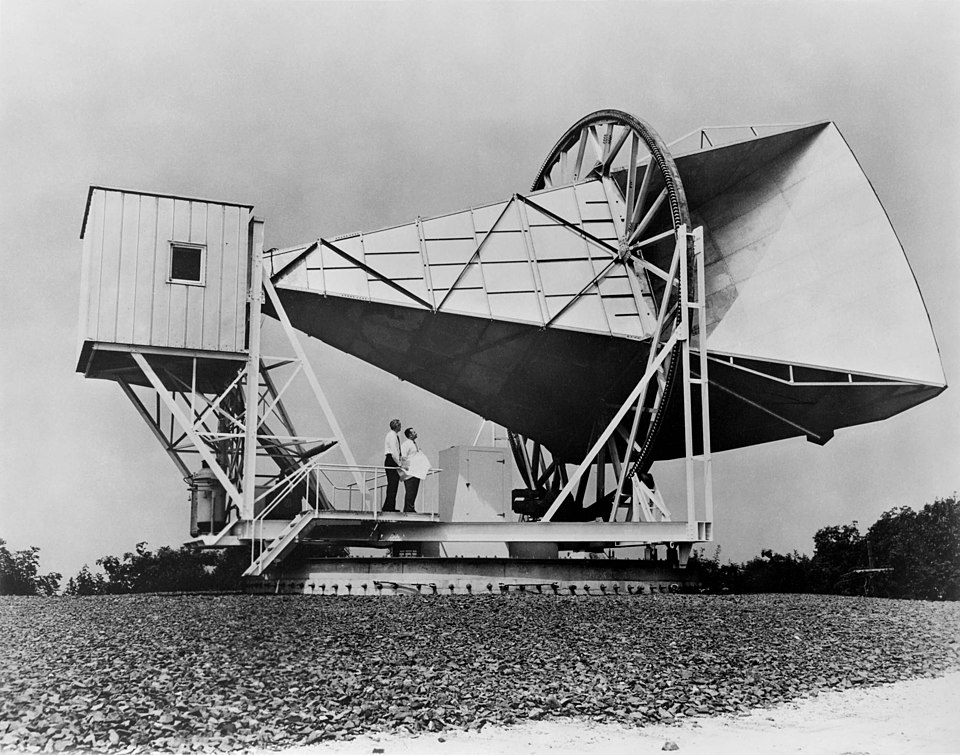

4. Cosmic Microwave Background, 1964

Engineers Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson hunted a stubborn hiss in a radio antenna. They cleaned, checked cables, and even shooed pigeons, yet the noise stayed. The signal matched a uniform glow at about 3 kelvin, predicted as afterglow from the Big Bang. Their unplanned find became the strongest evidence that the universe was once hot and dense. Later satellites mapped tiny temperature ripples across the sky, helping scientists estimate the age of the universe and how galaxies formed.

5. Microwave Heating, 1945

Working near a magnetron, engineer Percy Spencer noticed a chocolate bar in his pocket had melted. He then popped corn and cooked an egg using microwave energy. Raytheon built early ovens by 1947, and by the 1970s home microwaves were common. The accident showed that water molecules absorb microwave radiation efficiently, heating food from the inside out. Today, microwave ovens shorten cooking times, help sterilize kitchen tools, and even support science labs that use controlled microwave heating for reactions.

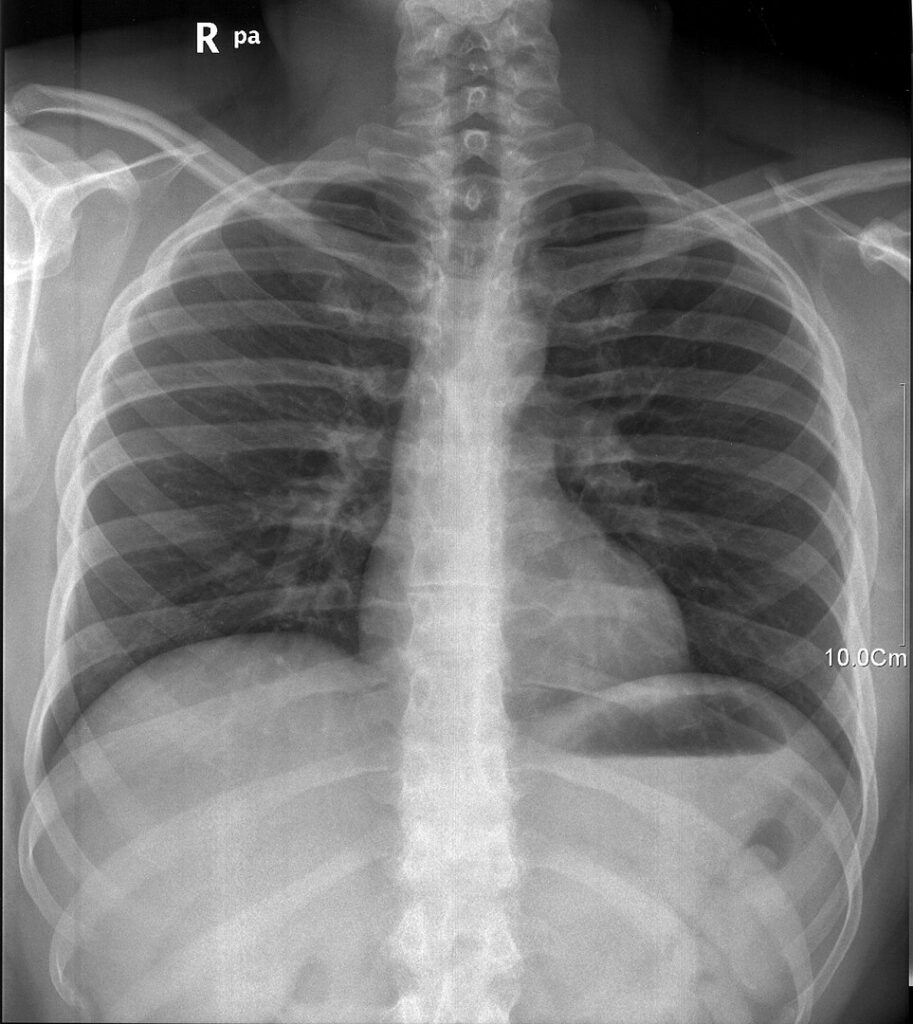

6. Teflon, 1938

Chemist Roy Plunkett expected a gas called tetrafluoroethylene to fill a cylinder. Instead, it had polymerized into a slippery white solid, polytetrafluoroethylene, later branded Teflon. The material resisted heat and chemicals and had very low friction. By the 1950s, it coated valves, cables, and eventually nonstick cookware. PTFE also shows up in medical devices and space suits where reliability matters. The surprise reaction introduced a class of fluoropolymers that engineers still choose when they need tough, nonreactive surfaces.

7. Safety Glass, 1903

French chemist Édouard Bénédictus dropped a glass flask coated inside with cellulose nitrate. It shattered but held together rather than flying into shards. He realized a plastic interlayer could make glass safer. Laminated glass soon appeared in car windshields and shop fronts, cutting injuries from sharp fragments. Modern versions use stronger plastics and multiple layers, but the principle is the same. A lucky drop in a lab led to a standard that protects drivers, students, and storefronts every day.

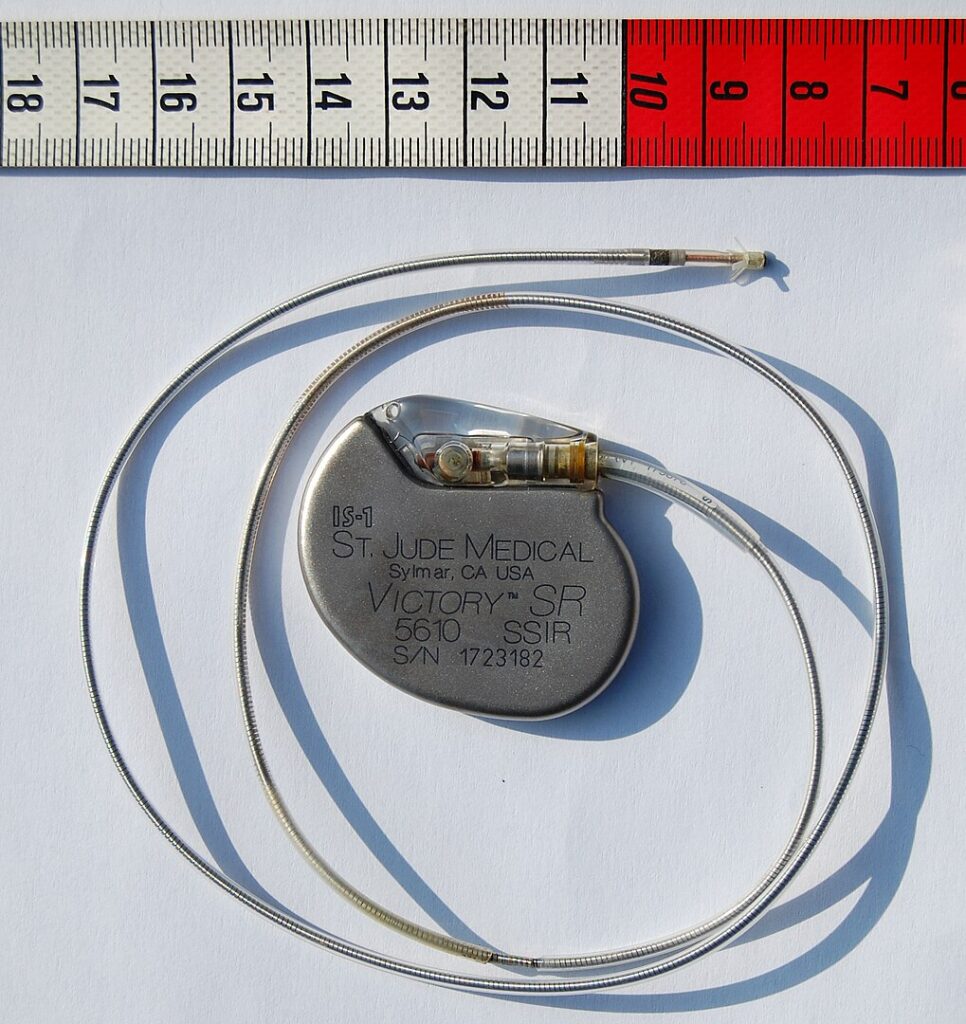

8. Implantable Pacemaker, 1956

Engineer Wilson Greatbatch accidentally installed the wrong resistor in a heart recording circuit. The device pulsed rhythmically, about the speed of a heartbeat. He realized it could drive the heart, not just listen. Working with surgeon William Chardack, he helped create an implantable pacemaker by 1958–1960. Early units used batteries sealed in biocompatible cases and extended lives for patients with slow or irregular rhythms. That wiring mistake evolved into life-saving tech used in millions of people worldwide.

9. Vulcanized Rubber, 1839

Charles Goodyear spilled a sulfur-rubber mix onto a hot stove and noticed the cooled piece stayed springy instead of gooey. Heating rubber with sulfur makes cross-links that resist melting and cracking. Vulcanization turned sticky sap into a durable material for tires, belts, and shoe soles. The process allowed reliable bicycle and car tires, which in turn sped up travel and industry. From playground balls to engine mounts, that accident gave everyday products toughness and bounce that raw rubber lacks.

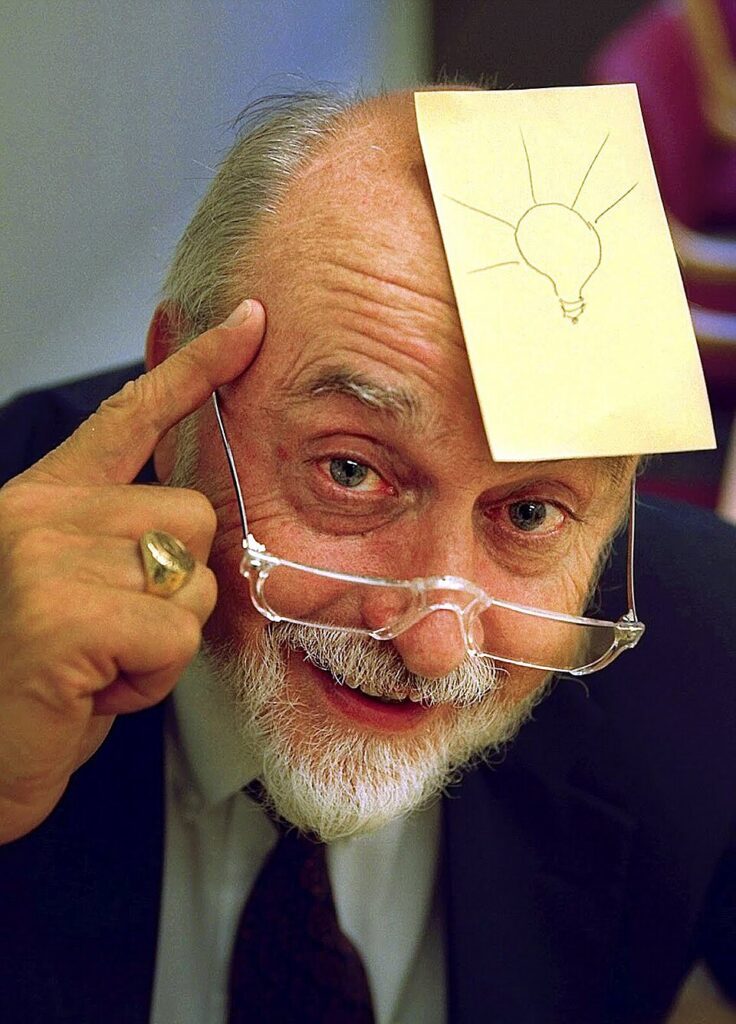

10. Post-it Note Adhesive, 1968–1980

3M scientist Spencer Silver made a weak, pressure-sensitive adhesive by accident. It did not hold strongly, but it stuck again and again. Years later, colleague Art Fry used it to anchor paper bookmarks that would not fall out of a hymnal. The idea became the Post-it Note, launched in 1980. The tiny sheets are now everywhere, from classrooms to labs. The science lesson, a failed search for a super-glue led to a new category of removable, reusable adhesives.