Book bans say more about fear than pages. Stories that confront violence, identity, faith, and power unsettle gatekeepers who try to shrink the public square. Yet these same narratives expand empathy, restore missing history, and show how language can carry grief and joy at once. When a title is challenged, its urgency sharpens, and the conversation it invites gets harder to dodge.

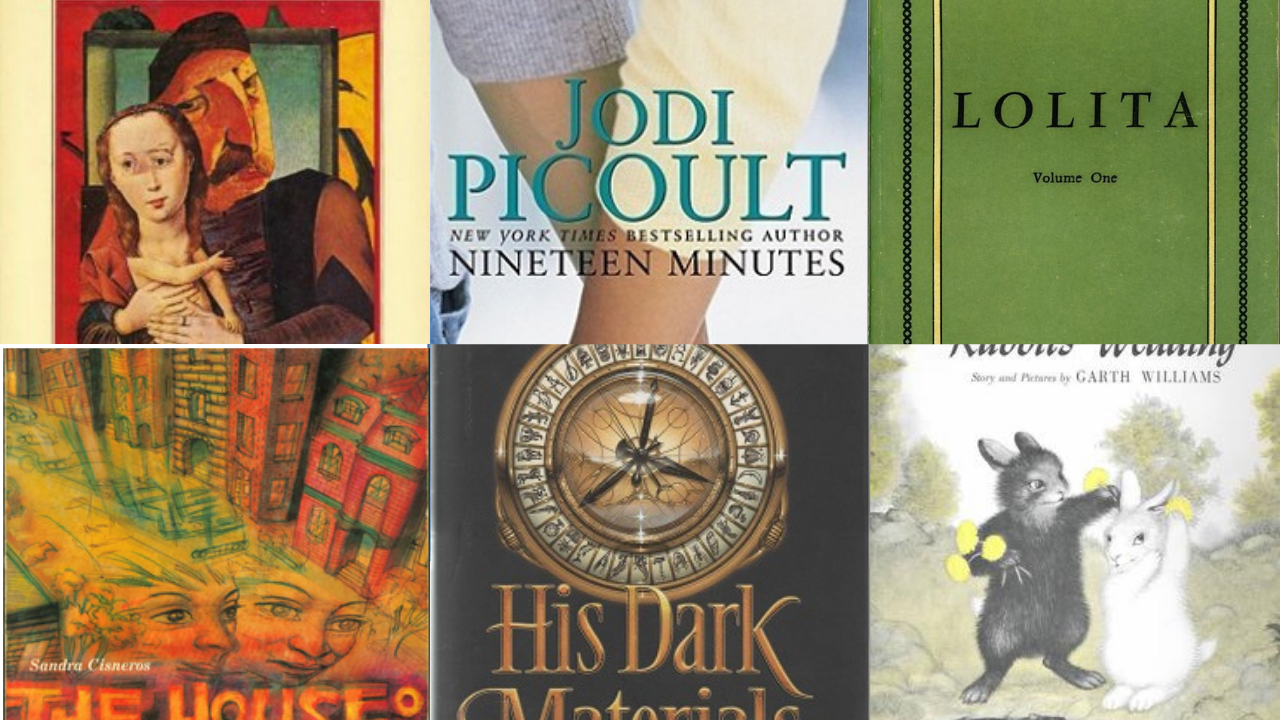

All Boys Arent Blue by George M. Johnson

A frank memoir in essays follows Black queer boyhood through family tenderness, harm, and self definition. Johnson mixes gentle kitchen table scenes with clear accounts of pain, never trading honesty for spectacle. The voice is direct, generous, and steady, which is exactly why censors bristle. Its pages model language for hard conversations at home and in classrooms. As testimony and literature, it widens who gets to come of age on the page and what safety can look like afterward.

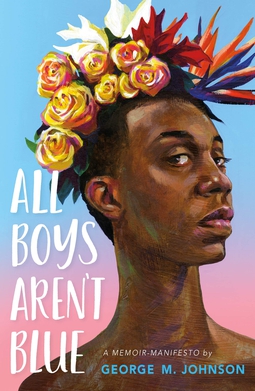

Nineteen Minutes by Jodi Picoult

Picoult examines a small town after a school shooting, mapping bullying, silence, and the speed at which blame moves. Legal strategy, parental fear, and teen secrets collide in a narrative that refuses easy villains while keeping faith with facts. The book is challenged for depicting violence, yet its aim is preventive clarity. It shows how warning signs accumulate, how institutions look away, and how healing begins only when a community names what it ignored.

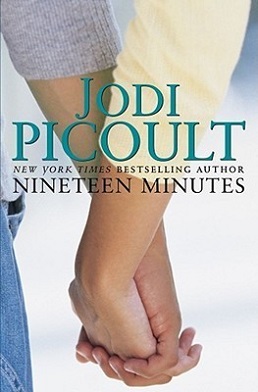

The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros

In luminous vignettes, Cisneros follows Esperanza as she learns a city block and herself at the same time. Compressed, musical sentences turn windows, sidewalks, and rented rooms into a whole cosmos. Challenges cite sexuality or poverty, but the heart of the novel is tenderness for ordinary ambition. Esperanza studies the rules and starts drafting her own. As craft, it proves a slim book can carry a city. As art, it keeps unfolding with every reread.

Beloved by Toni Morrison

Morrison renders the afterlife of slavery as memory made flesh, where a house holds grief that refuses to stay quiet. Sethe’s choices echo across time, testing what love can justify and what freedom costs. The prose is sumptuous and exact, cutting to the bone while lighting each scene with lyric heat. Bans target the brutality, but the refusal to sanitize is the point. Naming the unthinkable restores stolen specificity and returns agency to the haunted.

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

A branching family saga begins with two half sisters on the Gold Coast and moves through centuries of war, migration, and reinvention. Each chapter feels complete, yet clicks into a larger design that tracks how slavery mutates into prisons and policy. Challenges go after its frankness, but the architecture invites understanding over shock. Gyasi gives history a pulse you can feel in the body, and leave with a map for how private love survives public harm.

A Time to Kill by John Grisham

Grisham’s debut stages a courtroom where ritual collides with bias. A father’s crime, an all white jury, and a Mississippi summer force a town to measure justice against rage and grief. The pace grips, but the endurance comes from moral friction that refuses clean answers. Challenges cite graphic content, yet the narrative confronts exactly what polite language hides. It is a thriller with teeth, a study of power behind procedure, and a prompt to look longer.

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

An unreliable narrator flatters himself in sentences so dazzling they nearly launder the crime. That is the design and the warning. The novel shows how rhetoric can groom, excuse, and mythologize abuse, then leaves readers with a sharpened resistance to charm. Bans chase the subject matter, but the book is not an endorsement. It is a lesson in voice, irony, and ethical doubt, proving how style can hide a theft and how careful reading can unmask it.

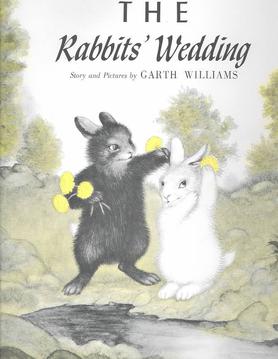

The Rabbits Wedding by Garth Williams

A tender picture book once drew censors for the marriage of a black rabbit and a white rabbit. The watercolor woods are soft, the story simple, the feeling steadfastly kind. Its banning history reads like a primer on projection, adults pouring panic into a gentle fable. As children’s literature, it models affection without sermon. As a cultural artifact, it shows how innocence can threaten brittle ideology and how grace embarrasses bad arguments.

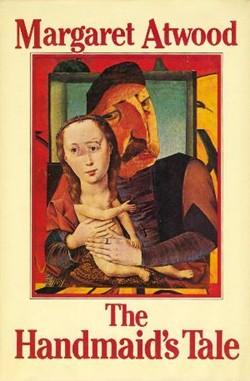

The Handmaids Tale by Margaret Atwood

Atwood imagines a theocracy where fertility becomes property and language is rationed. Worldbuilding details uniforms, ceremonies, and stolen names that recode daily life. Challenges track the sexual and political content, but the force is diagnostic, not lurid. It maps how freedoms erode by increments until neighbors enforce what once seemed unthinkable. Decades on, its metaphors keep refreshing, offering a toolkit for reading power and the small bargains that feed it.

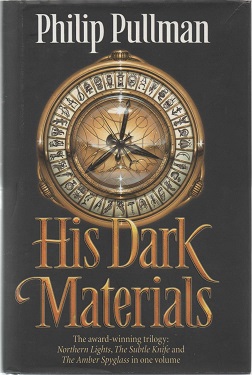

His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman

Pullman builds a sweeping fantasy that questions authority and treats curiosity as a moral duty. Dæmons, dust, and parallel worlds carry adventure while smuggling in philosophy about consciousness and freedom. Church censure helped cement its reputation, yet the trilogy rewards attention with courage earned and betrayals that hurt. Big ideas land in the body, not just the head, which is why young readers and adults keep returning to it with fresh questions.