America’s growth relied on Chinese workers, yet many lived at the bottom of the ladder. From the 1850s to the 1940s they dug canals, blasted tunnels, cooked in camps, and slept in crowded wooden rooms. Laws like the Page Act of 1875 and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 cut off families and wages. Violence and raids followed. Some fought back in court or through mutual aid. This guide uses dates, places, and rules, so hidden struggles become clear and human.

1. Page Act 1875 and Exclusion 1882 Block Families

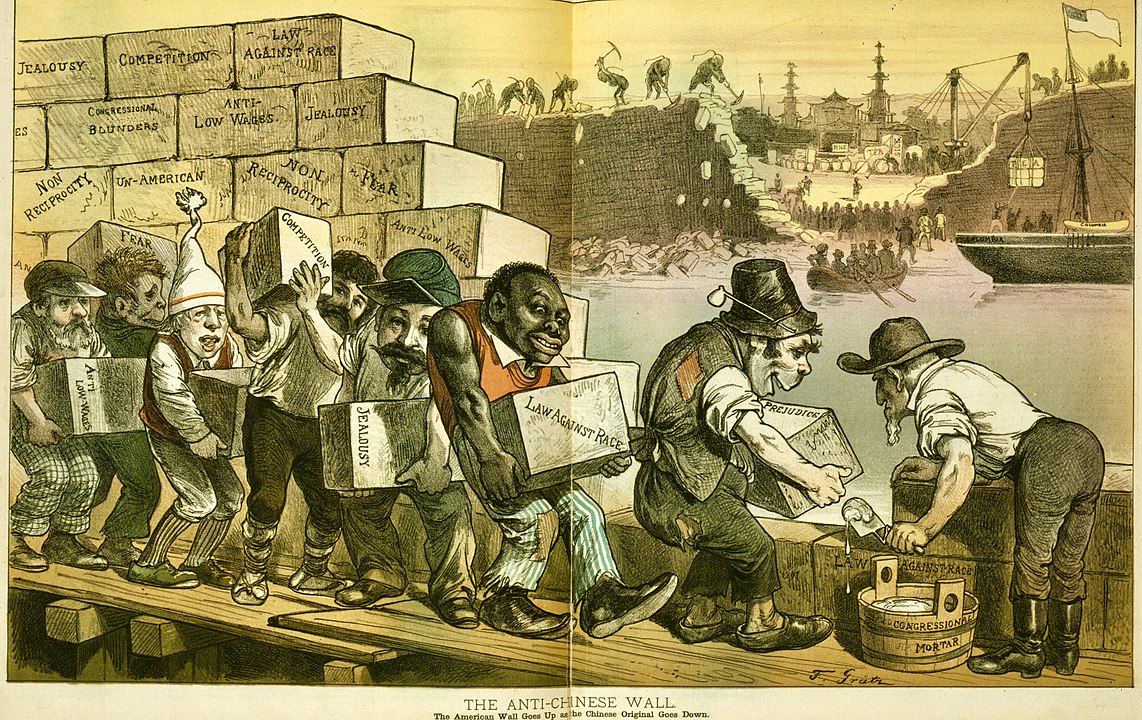

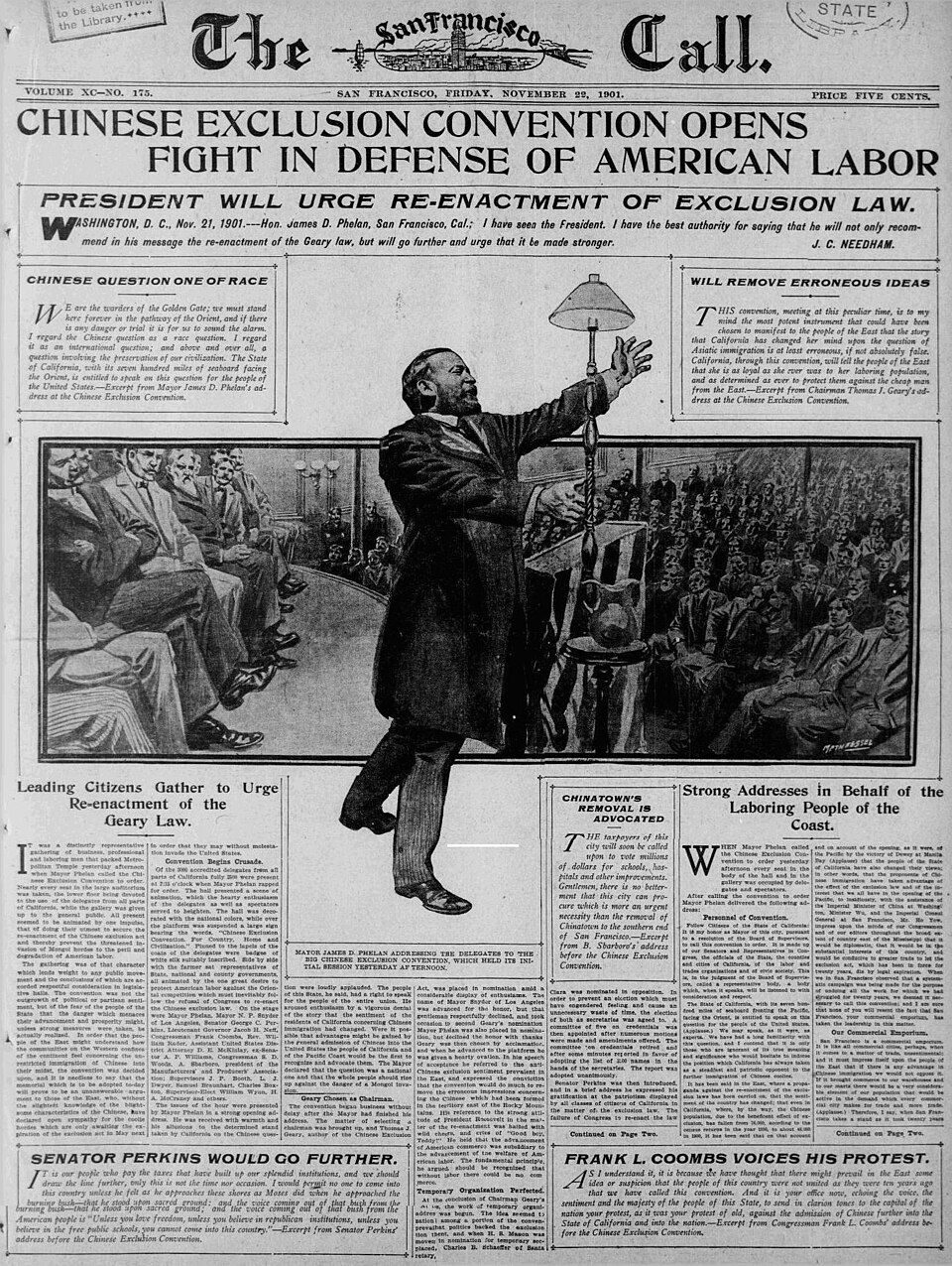

Two federal laws reshaped lives. The Page Act of 1875 blocked many Chinese women from entering, often by labeling them “immoral.” The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 then barred most laborers, the first U.S. ban aimed at a nationality. The Scott Act of 1888 voided reentry papers, stranding about 20,000 travelers outside the country. In 1892, the Geary Act demanded certificates of residence or arrest. These rules split households and turned paychecks into survival plans instead of paths to reunion.

2. Railroad Work and the 1867 Sierra Strike

Chinese crews built the Central Pacific over the Sierra Nevada. From 1865 to 1869, as many as 12,000 blasted granite and shoveled snowdrifts taller than houses. In June 1867, thousands struck for better pay and shorter hours. Tunnels like Summit Tunnel No. 6 advanced inches per day. Nitroglycerin appeared in 1867, speeding progress but raising danger. Many deaths went uncounted. When the golden spike was driven at Promontory in 1869, workers who laid miles of track saw little credit and low wages.

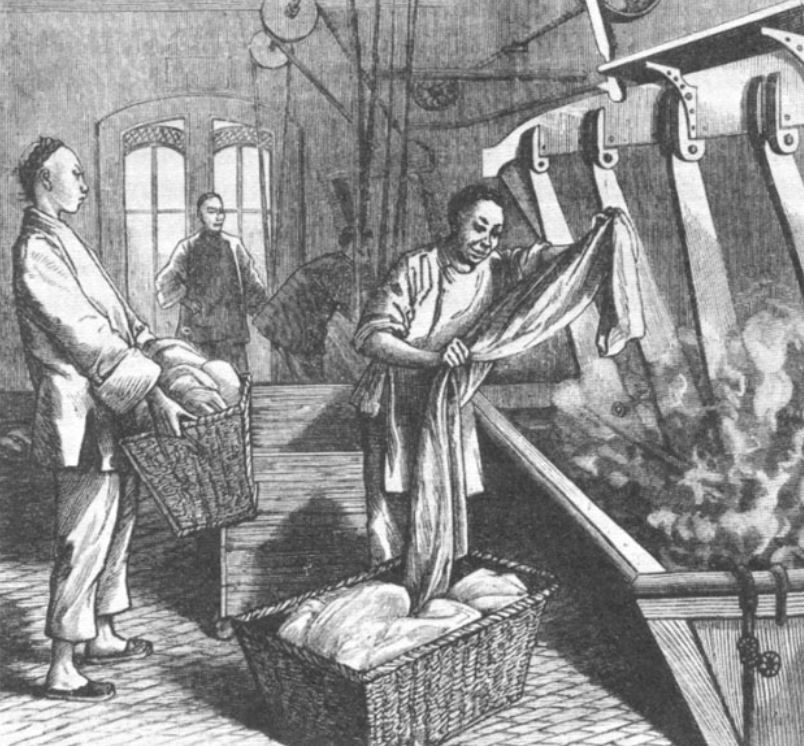

3. Chinatowns, Laundry Laws, and Yick Wo 1886

Cities targeted daily work. San Francisco forced laundries in wooden buildings to get hard to win permits, even though most shops were wooden. In 1886, the Supreme Court ruled in Yick Wo v. Hopkins that a neutral law enforced with bias violates equal protection. Other local rules, like the 1873 “queue” ordinance and cubic air standards, also hit tenants in crowded rooms. Despite barriers, storefront temples, herb shops, and language schools kept neighborhoods alive and gave new arrivals places to sleep.

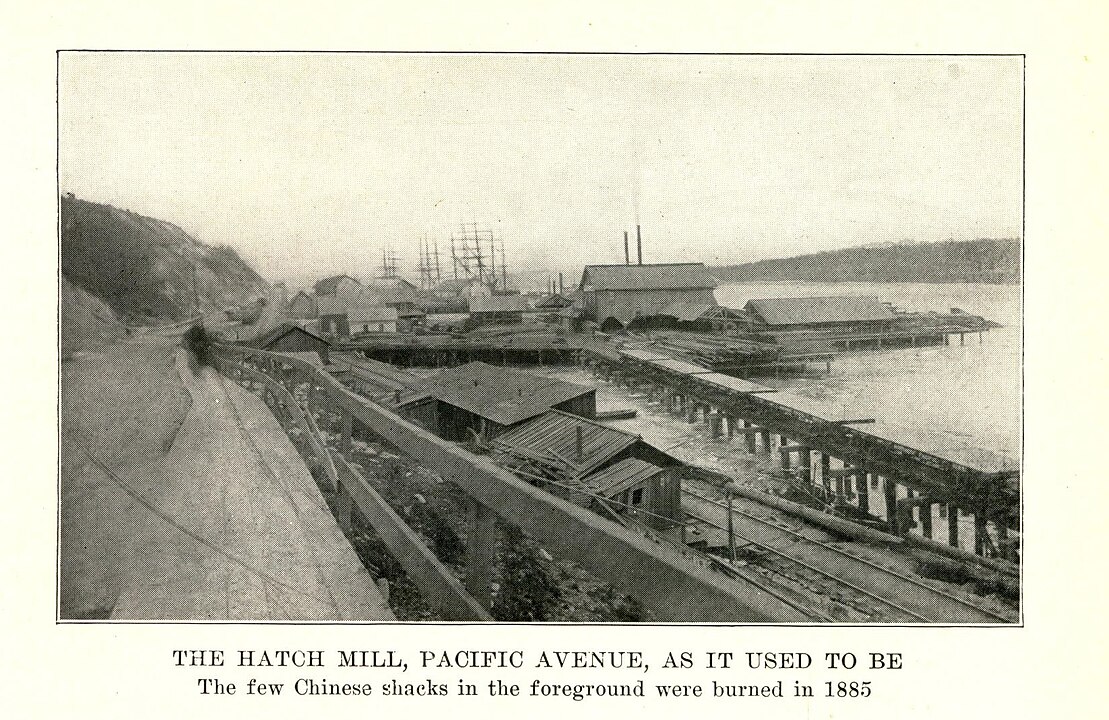

4. Mob Violence, 1885 Tacoma and Rock Springs

Anti-Chinese mobs attacked towns across the West. On September 2, 1885, in Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory, white miners killed dozens of Chinese coworkers and burned homes. Two months later, on November 3, 1885, Tacoma leaders forced hundreds to march out in a mass expulsion. Seattle faced riots in February 1886. Few attackers were punished. These events emptied streets and broke families. If you visit memorial sites or rail grades today, stay on marked routes and follow posted safety signs near tracks and cliffs.

5. Angel Island Detention, 1910 to 1940

After 1910, many arrivals met locked doors at Angel Island in San Francisco Bay. Detainees faced long interrogations, with questions about roof eaves and the number of house steps to test “paper son” claims after the 1906 quake erased records. Detention could last weeks or many months. Poems carved in barracks walls described loneliness and hope. A 1940 fire closed the station. In 1997 the site gained National Historic Landmark status, preserving rooms where immigration law turned waiting into hardship.

6. Cannery Rows and Farm Camps on the Coast

Work moved with the seasons. Chinese crews packed salmon in Washington and Alaska from June to July, hauling 50 pound boxes in wet sheds. Others dried shrimp around San Francisco Bay or cut asparagus in California’s Delta each spring. Bunkhouses were crowded, pay was low, and company scrip sometimes replaced cash. Foremen set long shifts that could stretch past 12 hours during peak runs. Yet cooks, herbalists, and letter writers traveled with crews, keeping food, medicine, and family news flowing between camps.

7. In Court, Rights Won and Lost, 1893 to 1898

Courts delivered both setbacks and lifelines. In 1893, Fong Yue Ting upheld deportations for those lacking federal certificates. In 1889, Chae Chan Ping approved harsh bans on reentry. Yet in 1898, United States v. Wong Kim Ark affirmed birthright citizenship under the 14th Amendment for a man born in San Francisco to Chinese parents. These cases set rules that shaped who could stay, who could return, and who belonged. Families learned statutes, kept receipts, and coached answers to survive inspections.

8. Bachelors’ Clubs, Six Companies, and Care

Unbalanced migration created bachelor blocks. In 1870, only a small fraction of Chinese residents were women, so lodging houses filled with men sharing narrow beds. Benevolent groups, known as the Six Companies in San Francisco by the 1850s, collected dues, mediated disputes, and shipped remains home. Tongs and family associations posted house rules, ran savings pools, and paid doctors when injuries from kitchens or track work piled up. Festivals like Lunar New Year offered rest, lanterns, and a moment to feel seen.

9. From Magnuson 1943 to Fairer Quotas in 1965

War changed policy. In 1943, the Magnuson Act repealed exclusion and allowed naturalization, but set a tiny quota of 105 immigrants per year. The War Brides Act of 1945 helped wives and children enter, reuniting some families after years apart. In 1952, updated laws kept national origins quotas in place. Real change arrived with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which ended those quotas and opened larger legal paths. New arrivals built on older networks to restart family life.

10. Learning the Past, Visiting Sites Safely Today

History lives in places. Angel Island’s preserved barracks, San Francisco’s Grant Avenue, and Utah’s Promontory grounds tell stories from 1869 to 1940 and beyond. Museum hours, ferry schedules, and park rules protect visitors and fragile buildings. Read posted signs, use sidewalks, and stay behind railings near water or tracks. Ask docents before photographing delicate walls with poetry. Bringing a notebook helps record dates and names. Respectful visits keep memory intact and honor people whose labor built railroads, streets, and waterfronts.