History still arrives in classrooms as neat tales with clean edges. Heroes stride in, conflicts wrap up on schedule, and messy details fall away. The trouble is that evidence rarely cooperates. New archives surface, perspectives widen, and long-ignored voices reframe what seemed obvious. When students see how power, economics, and culture shape events, the past stops feeling like a bedtime story and starts reading like the country itself. That clarity builds judgment, which is what history class should deliver.

Columbus Discovered America

Many lessons still crown 1492 as a beginning, ignoring thriving Indigenous nations with cities, astronomy, and trade that stretched across continents. Columbus reached Caribbean islands already mapped in Native memory and soon set off a chain of conquest, disease, and forced labor that remade the Atlantic. Teaching encounter rather than discovery restores agency to Taino, Nahua, and Maya communities, and it links exploration to empire and profit. The story widens, and students see causes rather than slogans.

The First Thanksgiving Was Pure Harmony

A harvest meal did happen, but it was part of a fragile Wampanoag-Plymouth alliance shaped by regional war, famine, and diplomacy. Cooperation bought time; it did not settle land claims or erase tension. Within decades, conflict exploded in King Philip’s War, and colonists expanded through treaties that advantaged them. Later proclamations turned a regional ritual into national symbolism. When Native accounts lead the lesson, students learn how alliances work under pressure and what was lost to make room for myth.

The Revolution Was Only About Taxes

The slogan about taxation misses deeper drivers like imperial rivalry, westward land speculation, and the politics of enslaved labor. Patriots argued for rights while Loyalists, Indigenous nations, and enslaved people weighed different promises and risks. Liberty language sat beside exclusions from the vote and fears of social upheaval. Seeing the war as ideological and economic, local and global, shows why independence freed some paths and closed others. Complexity does not weaken the cause; it explains its costs.

The Constitution Delivered Full Democracy

The 1787 design concentrated power and limited the electorate to a narrow group, while protecting slavery through clauses and compromises. Senators were not directly elected until the 20th century, and many Americans lacked the franchise for generations. Amendments, organizing, and court fights expanded rights step by step, often after crisis. Framing the Constitution as a starting point rather than a finish line helps students grasp how movements bend law toward broader belonging. Progress arrives through pressure, not destiny.

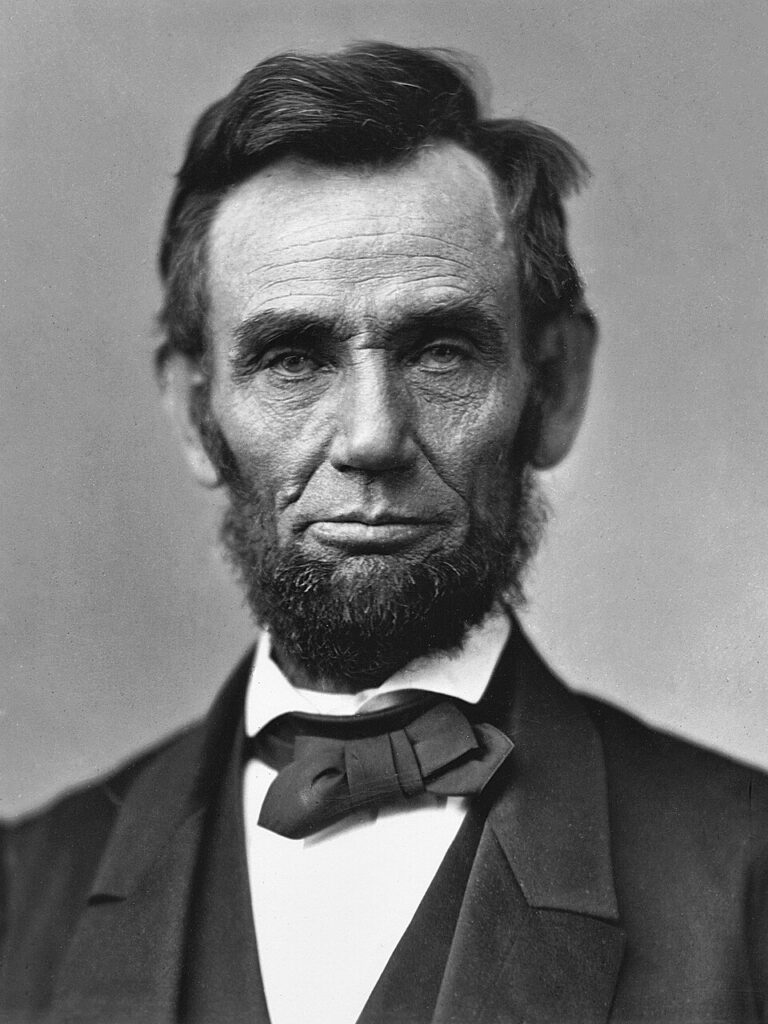

The Civil War Wasn’t About Slavery

Secession statements, speeches, and newspapers make the motive plain: preserving and expanding slavery was the core dispute. States rights talk usually meant the right to own people. Economics and honor mattered, but they orbited bondage. Centering slavery clarifies why emancipation threatened the old order and why Reconstruction faced violent resistance. It also explains the stakes of Black military service and political leadership. When the cause is named accurately, the aftermath finally makes historical sense.

Lincoln’s Proclamation Freed Everyone Overnight

The Emancipation Proclamation applied to areas in rebellion and worked through military power, leaving slavery in border states until later actions and the 13th Amendment. Freedom arrived unevenly, enforced by Union advances and the courage of enslaved people who fled, enlisted, and negotiated wages and safety. Juneteenth marks delayed enforcement in Texas rather than a single turning point. Teaching emancipation as a process honors Black agency and shows how law, war, and grassroots action braided into lasting change.

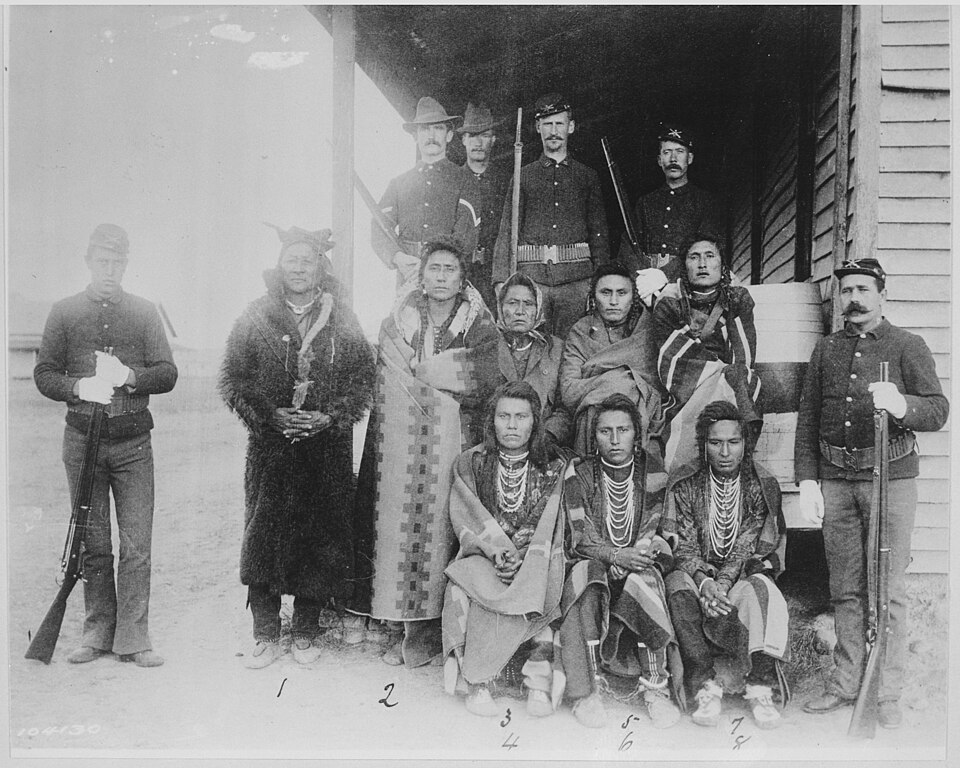

The West Was Empty Until Pioneers Arrived

Textbook frontiers often erase Native nations with mapped homelands, agriculture, trade, and sacred sites. U.S. expansion moved through treaties broken, removal campaigns, allotment policies, and boarding schools that attacked culture. Mexican, Chinese, Black, and Indigenous workers built railroads and towns alongside ranchers and miners, shaping law and labor. Replacing the lone cowboy with a crowded landscape reveals how capital, policy, and resistance formed the region. The West becomes a contested place, not a blank slate.

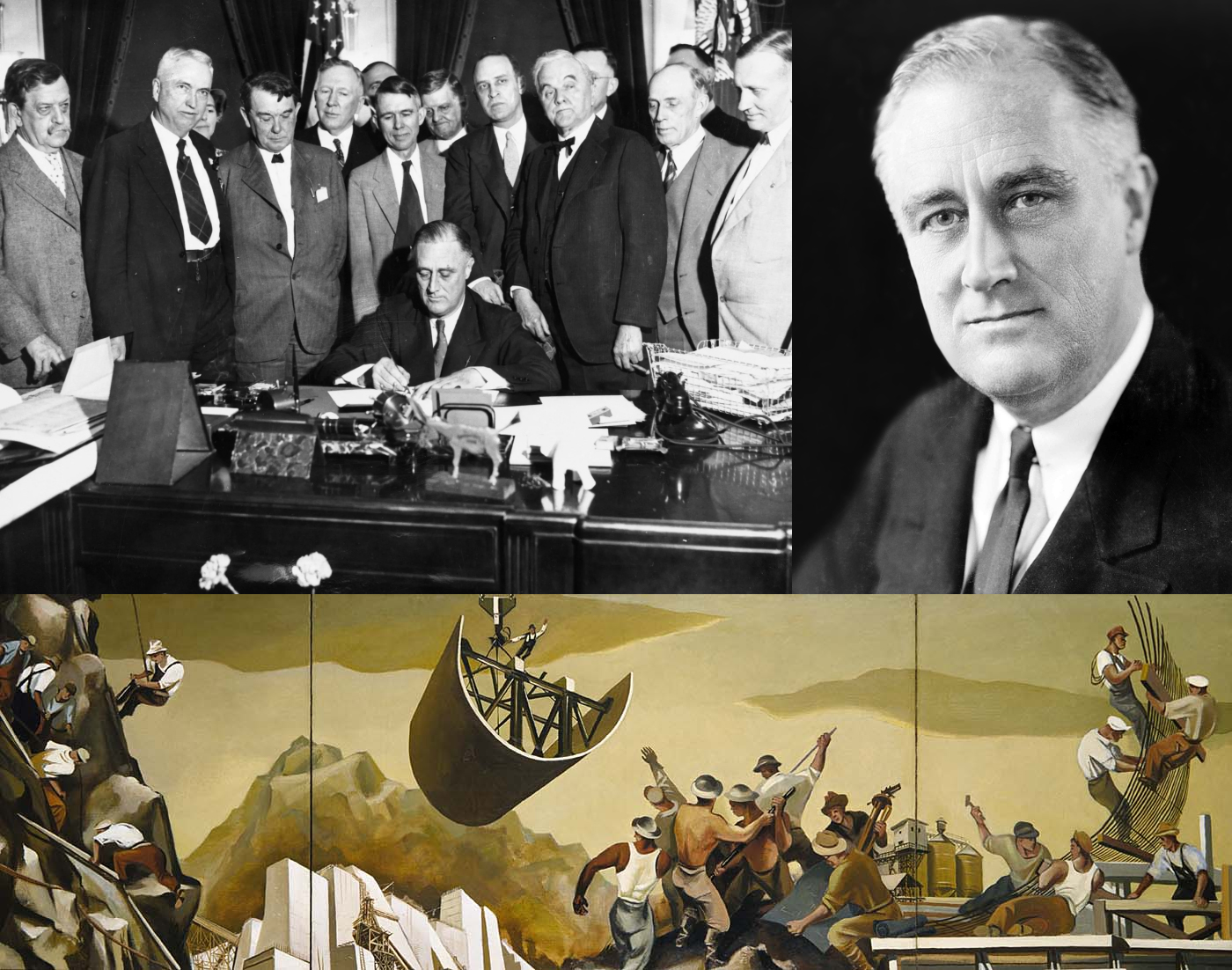

The New Deal Ended the Depression By Itself

New Deal programs stabilized banks, funded jobs, and built infrastructure, yet unemployment stayed high until wartime production surged. Policies often excluded or underpaid Black, Mexican American, and women workers, baking inequities into benefits and housing. Labor organizing, local coalitions, and legal fights shifted power on factory floors and in city halls. Seeing the 1930s as uneven experimentation helps students judge what government can do in crisis and what it tends to miss without pressure from below.

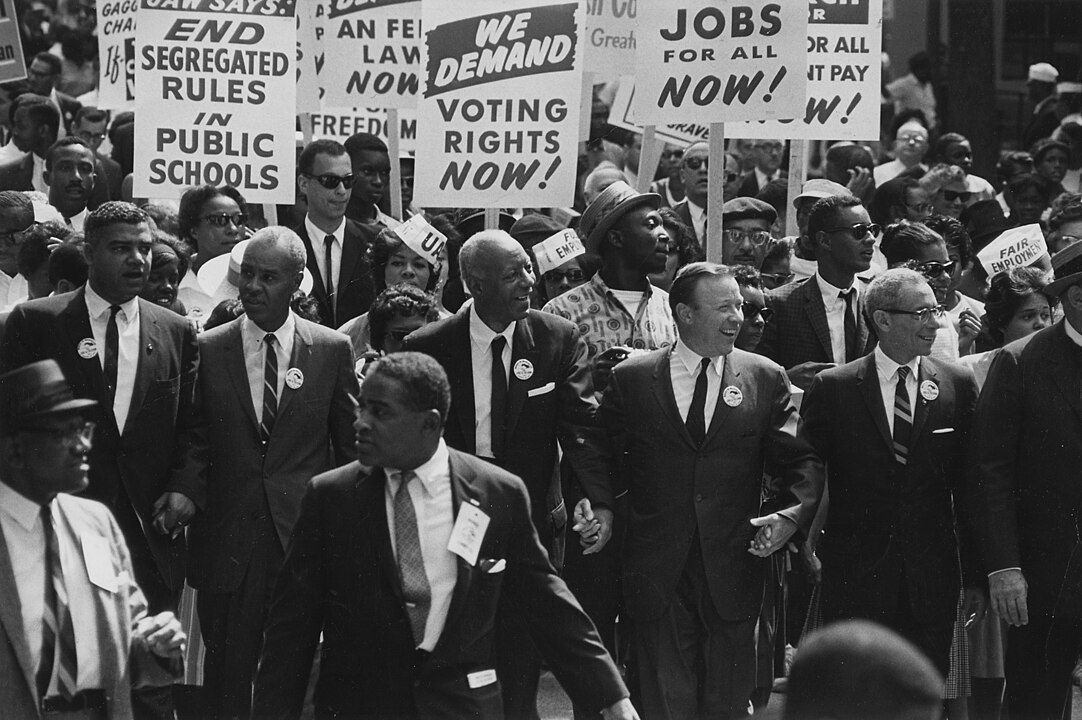

The Civil Rights Movement Was Inevitable And Finished

Victories in the 1960s were won, not fated. Organizers trained, raised money, debated tactics, and faced jails and bombs. Laws curbed segregation and voter suppression, but access gaps, housing discrimination, and wealth inequality persisted. The movement evolved, linking Black, Native, Latino, Asian American, immigrant, queer, and disability justice campaigns that use courts, ballots, and policy. Teaching the work as ongoing equips students to recognize backsliding and to measure progress by outcomes, not headlines.