Scientists understand a lot about how the body works, yet some everyday behaviors remain puzzling. Popular lists highlight open questions like fingerprints or the appendix, but many active mysteries involve the nervous system. Examples include why yawns spread, what dreams are for, why hiccups start, and why tingles from whisper videos feel relaxing. Researchers test ideas with brain scans, lab tasks, and clinical studies, but several mechanisms remain incomplete or contested. Here are seven automatic things your body does that science is still piecing together.

1. Yawning spreads and may cool the brain

Yawns happen across species and can be contagious, but their core function is debated. Evidence supports a thermoregulation idea where yawning helps cool the brain, based on animal and human data linking yawns to temperature changes. Other work ties yawning to arousal shifts like drowsiness and boredom, not simple oxygen drops. Contagious yawning may relate to social cues, yet findings are mixed. Bottom line, cooling and arousal control both have support, and no single theory explains every case.

2. Hiccups are a reflex with unclear purpose

A hiccup is a sudden diaphragm contraction followed by vocal cord closure, producing the “hic” sound. Medicine classifies them by duration, from brief to persistent or intractable, and long cases can signal illness or nerve irritation. The reflex pathway is mapped, yet why humans retain it is uncertain. Hypotheses include leftover brainstem patterns from early development or a role in removing swallowed air in infants, but hard proof is limited. Treatments target triggers, not a definitive root cause.

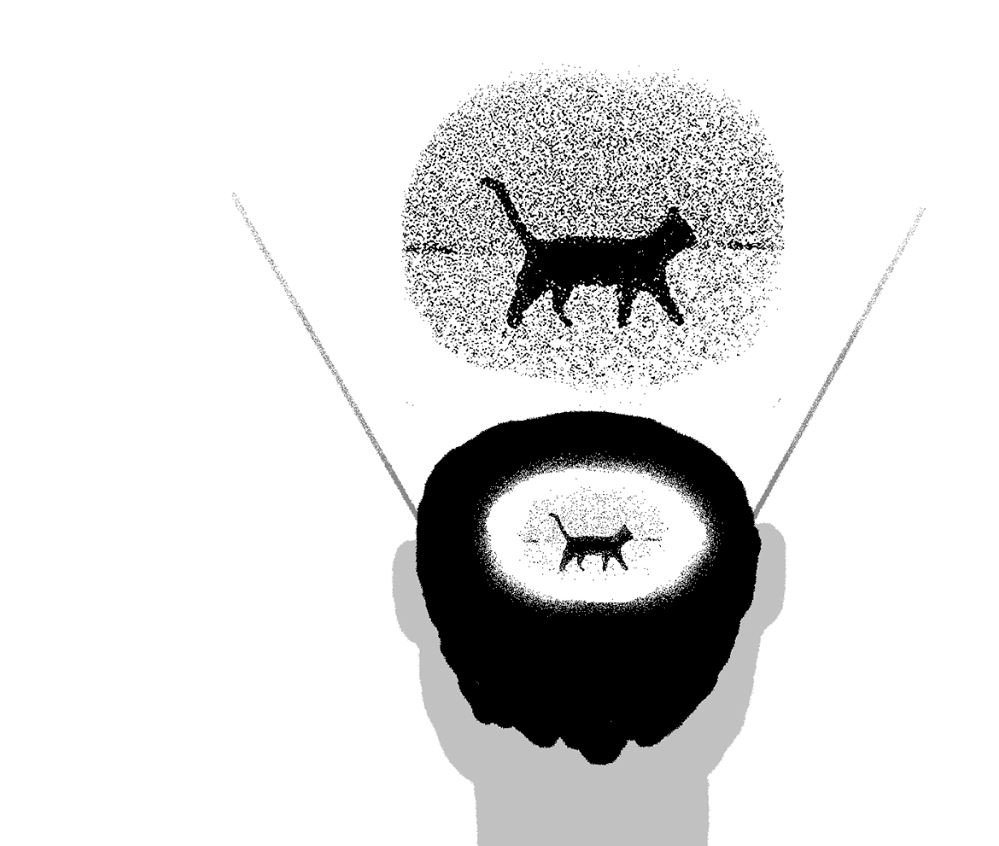

3. Dreams shape emotion and vision, but consensus is missing

Dreams arise with complex brain activity during sleep, especially REM, and support several competing theories. Some studies suggest an emotion regulation role, where dreams safely process strong feelings, while others propose defensive activation that keeps the visual cortex active at night. Classic neuroscience reviews show dreaming links to visual imagination and development, yet no single function explains all dream content. The field agrees dreams are biologically real, but their main purpose remains under debate.

4. The placebo effect changes symptoms without active drugs

Placebos can reduce pain and alter brain activity even when a pill has no active ingredient. Mechanisms include expectation and classical conditioning, with imaging studies showing changes across pain and emotion networks. Adolescents and adults both show measurable placebo responses, yet researchers still debate how context, learning history, and genetics interact to produce benefits or nocebo harms. We know the effect is real and neurobiological, but its full recipe varies by person and condition.

5. Déjà vu feels familiar for reasons scientists still test

Déjà vu is the sudden feeling that a new moment has happened before. Leading ideas suggest memory conflict, where expectation signals misfire and make a novel scene feel familiar, but direct tests are challenging outside the lab. Reviews describe it as a metacognitive warning that something went wrong in recognition, not a psychic event. Triggers may include similarity to previous layouts or stress and fatigue, yet the precise neural timing remains an active research question.

6. Goosebumps appear with cold and strong feelings

Goosebumps, or piloerection, come from tiny muscles attached to hairs that contract under sympathetic nervous system control. They show up with cold exposure and also during powerful music or awe, but why emotions trigger them is not fully settled. Some researchers link emotional piloerection to chills and approach motivation, while others study rare people who can activate it voluntarily. The thermoregulation role is clear in animals, yet the human emotional pathway is still being mapped.

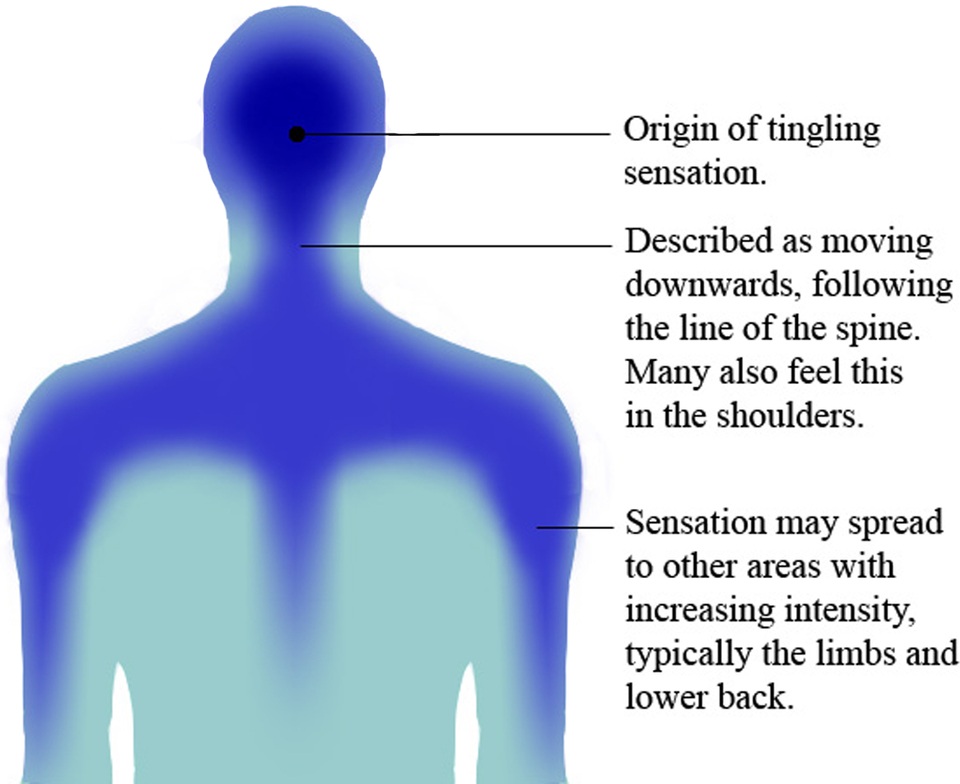

7. ASMR tingles relax many viewers; the mechanism is uncertain

ASMR videos often cause scalp-to-spine tingles and calm feelings in some people. Brain studies and experiments report mood improvements and stronger tingles with combined audio and visual triggers, but scientists have not pinned down one mechanism. Early work points to attention, expectation, and somatosensory engagement, with individual differences that make effects uneven. Clinically, ASMR may help some people wind down, yet standardized protocols and long-term studies are still in progress.