Thanksgiving carries a warmer glow than its beginnings. The 1621 harvest at Plymouth was real, but it was neither a national origin story nor a polished feast. Wampanoag diplomacy, colonial uncertainty, and seasonal hunger shaped the table more than legend. Over centuries, fast days, proclamations, and advertising remade the meaning into a shared ritual. Seeing the layers of celebration, survival, grief, and repair does not dim the holiday; it offers a fuller history to hold with family memory. That honesty makes gratitude stronger.

The 1621 Gathering Was Not Called Thanksgiving

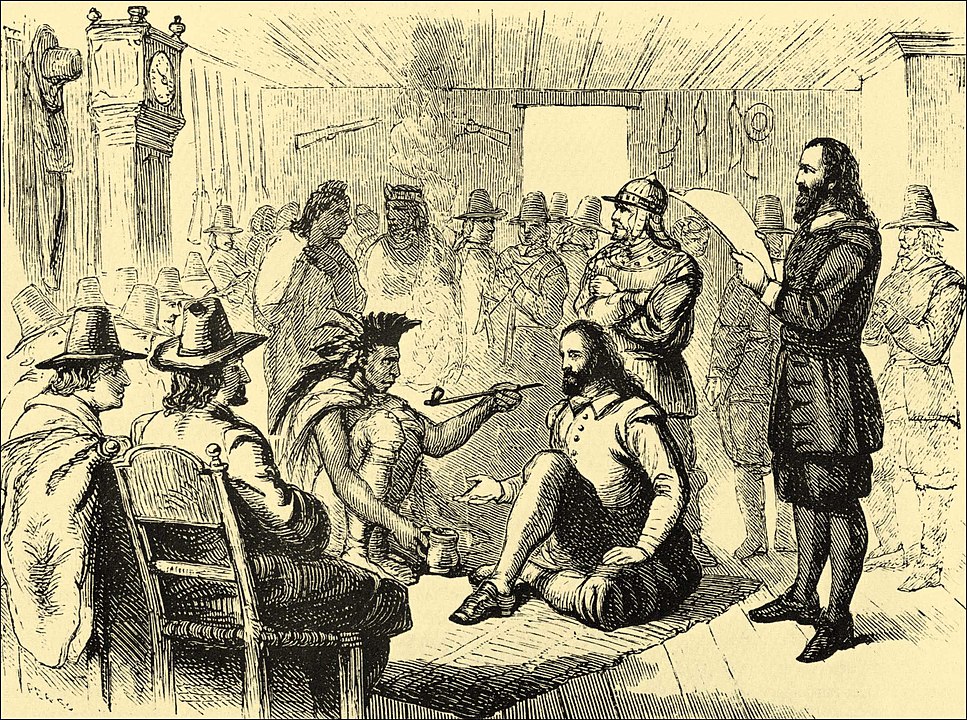

The 1621 gathering at Plymouth ran for days and centered on diplomacy and provisioning. Wampanoag hunters brought venison, while colonists offered waterfowl, corn, and late produce. No fixed menu, no seating plan, and no founding script. In the 1600s the word thanksgiving usually meant a religious observance after hardship, not a feast. Only later did storytellers crown 1621 as the first Thanksgiving, smoothing away hunger, fear, and fragile alliances to fit a comforting origin tale.

Thanksgiving Once Meant Fasting And Prayer

In the 17th century a day of thanksgiving usually meant church services, sometimes with fasting, called after crisis or relief. Colonies proclaimed such days for rain, peace agreements, or military victories, and also in the wake of violence. Feasting was not the point. Gratitude was communal, conditional, and public, more sermon than supper. The table centered holiday arrived later, after proclamations gave way to parades, recipes, and a calendar slot families could plan around.

Wampanoag Agency Shaped The 1621 Moment

Massasoit’s visit signaled treaty building, not a cameo in a colonial pageant. Wampanoag men arrived armed because diplomacy on a precarious frontier required readiness. Food sharing affirmed obligation and respect, but also strategy shaped by pandemic losses and shifting power. For Indigenous communities, the event sits inside a longer story of survival and negotiation. Seen that way, the meal is a political encounter, not a simple gift exchange or a quaint harvest party.

A Magazine Editor Helped Create The Tradition

A 19th century editor, Sarah Josepha Hale, spent decades urging governors and presidents to adopt a national Thanksgiving. Her campaign framed the day as a unifying domestic ritual. In 1863, with the Civil War raging, Abraham Lincoln proclaimed a national observance to steady a fractured country. The tradition stuck, strengthened by women’s editorial work, church notices, and newspapers. A holiday that feels ancient owes much to persistent advocacy, print culture, and a need for shared solace.

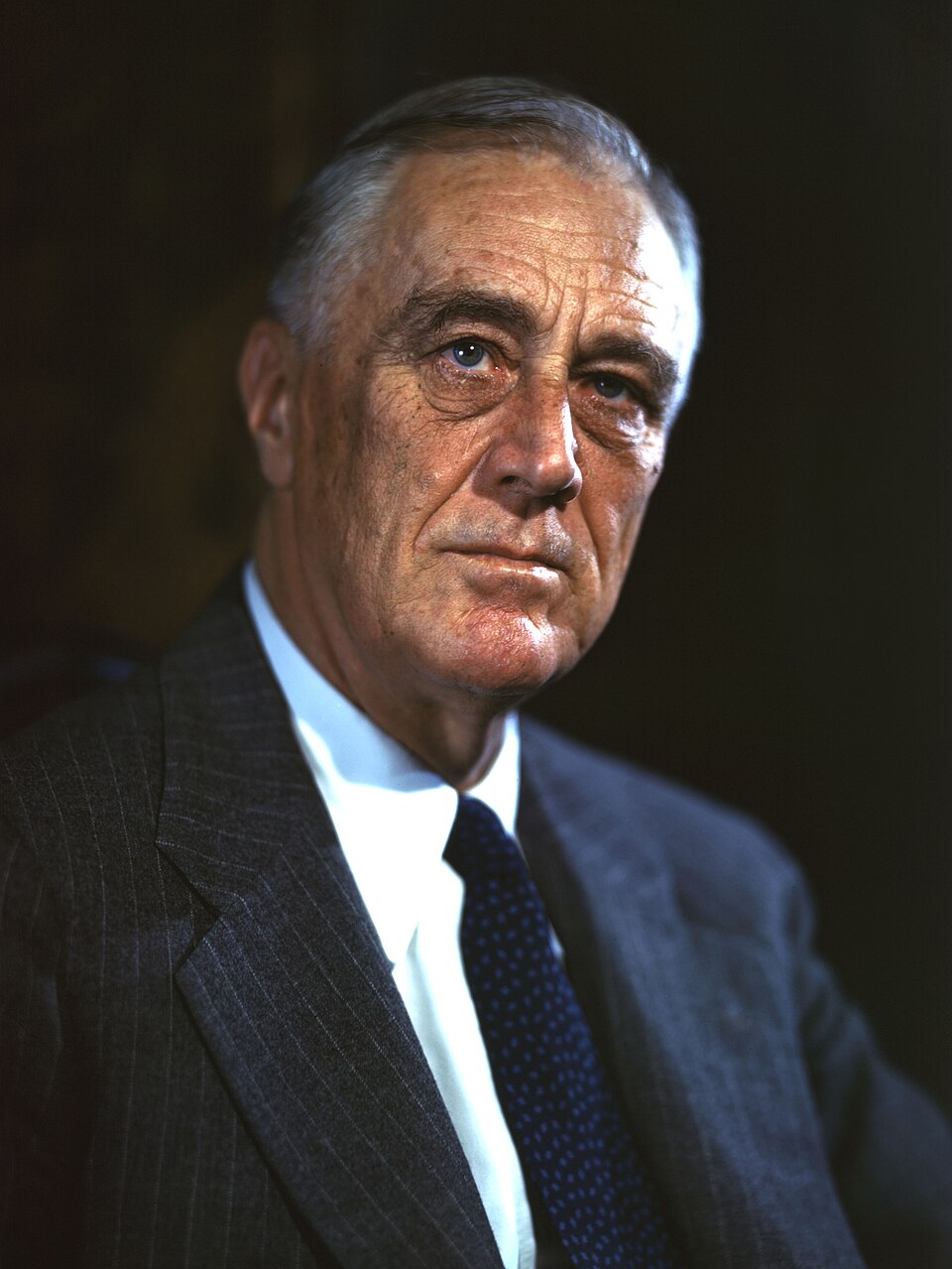

The Date Was Not Settled Until 1941

Thanksgiving moved around for years, with states choosing different November days. In 1939 Franklin D. Roosevelt shifted the date one week earlier to stretch holiday shopping, a change critics nicknamed Franksgiving. Confusion followed. After two uneven years, Congress fixed the holiday in 1941 on the fourth Thursday of November. That decision locked a national rhythm of school breaks, parades, and travel. What many assume is colonial continuity is a modern compromise shaped by commerce.

Many Observe A National Day Of Mourning

Since 1970, organizers in Plymouth have observed a National Day of Mourning that honors Indigenous lives lost to colonization and challenges celebratory myth. The gathering features speeches, prayer, and marches, insisting that remembrance hold grief alongside gratitude. For many Native families, the season carries both community warmth and historical weight. Making space for this parallel observance does not cancel the holiday; it deepens it, inviting dignity, listening, and repair.