For a long time, many historians treated powerful women as exceptions instead of foundations. Closer work in villages, courts, and archives told a different story. Across continents, researchers kept encountering communities where land, lineage, and public authority run through women’s hands. Some are ancient systems still adapting to modern law; others are recent experiments born from crisis and courage. Taken together, they unsettle simple ideas about patriarchy and show how family, faith, and power can be organised around mothers and daughters.

Minangkabau, Indonesia

In the hills of West Sumatra, Minangkabau families trace descent and land through women. Ancestral rice fields and long wooden houses belong to a mother’s clan, while men are expected to travel for trade or religious study. Husbands are often visitors in their wives’ homes, not anchors of property. Islamic learning sits alongside customary law, so female landowners quietly stabilise both family welfare and village politics, even as debates over modern inheritance law reshape that landscape.

Mosuo Around Lugu Lake, China

Around Lugu Lake, Mosuo households are organised around a senior woman, not a married couple. Daughters stay in their maternal home for life, children belong to the mother’s clan, and maternal uncles raise them. Romantic partners often have night visits known as walking marriages, returning to their own family houses by morning. Because property, caregiving, and daily authority sit with women, early outsiders struggled to fit Mosuo life into standard family models built around fathers and formal weddings.

Khasi Hills Of Meghalaya, India

Among the Khasi in Meghalaya, the youngest daughter inherits the ancestral house and most family property. Children take the mother’s clan name, and husbands usually move into or live near their wives’ households. That structure gives daughters strong security in old age and keeps ancestral land from fragmenting. At the same time, debates over men’s roles and modern legal reforms show a society still negotiating how matrilineal descent and contemporary expectations of gender and work can fit together.

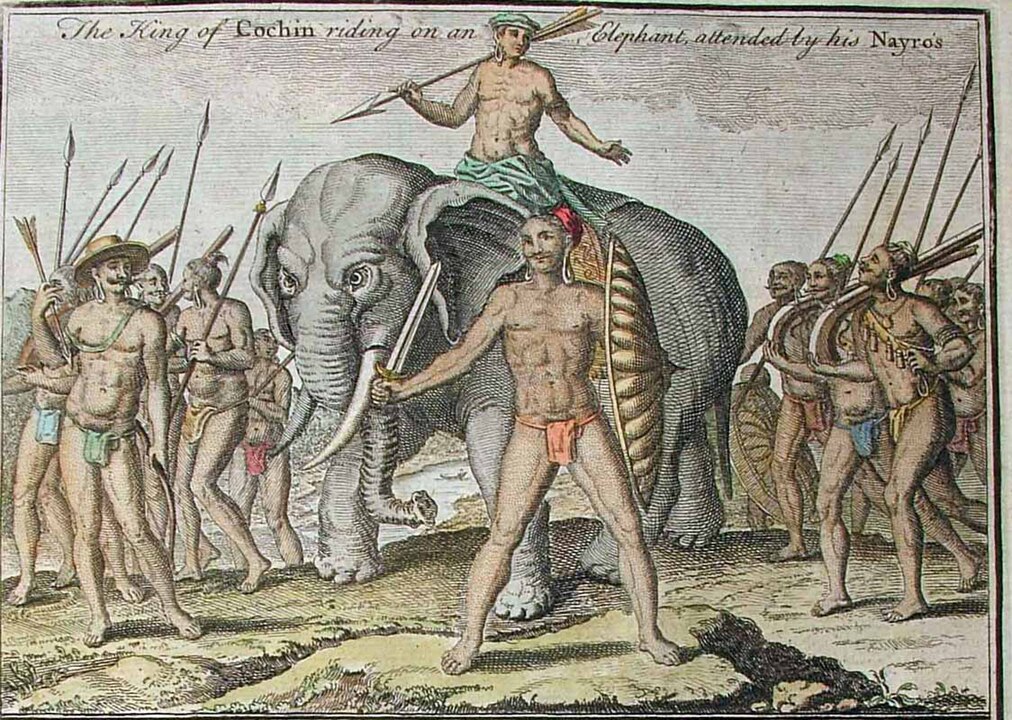

Nair Tharavads In Kerala, India

Historical Nair tharavads in Kerala were sprawling joint families descended from a founding ancestress. Membership followed the maternal line, children belonged to their mother’s home, and property was divided among women when a house split. A senior maternal uncle, not a husband, often controlled common assets and major decisions. Men visited wives at night and returned to their own tharavads by day. Modern reforms and urban life weakened this system, but its logic still shapes memory and disputes around land and marriage.

Haudenosaunee Clan Mothers, North America

Within the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, clan mothers hold authority that startled early European observers. Clans are traced through women, and clan mothers select the male chiefs who sit in council, advise them, and can remove them if they fail the people. They also help decide questions of war and peace and safeguard longhouse property. Their power, grounded in consensus and responsibility, later influenced suffragists who looked to Haudenosaunee governance as proof that women could hold formal political authority without social collapse.

Akan Queen Mothers In Ghana

In many Akan states, the queen mother is a co-ruler rather than a ceremonial figure. She keeps royal genealogies, helps choose the chief from the matrilineage, and can press for his removal if he abuses power. Her council hears disputes, especially those involving families, markets, and young people. Recent work has highlighted how queen mothers shape local governance, public health campaigns, and conflict resolution, even when colonial archives downplayed them in favor of kings and male chiefs.

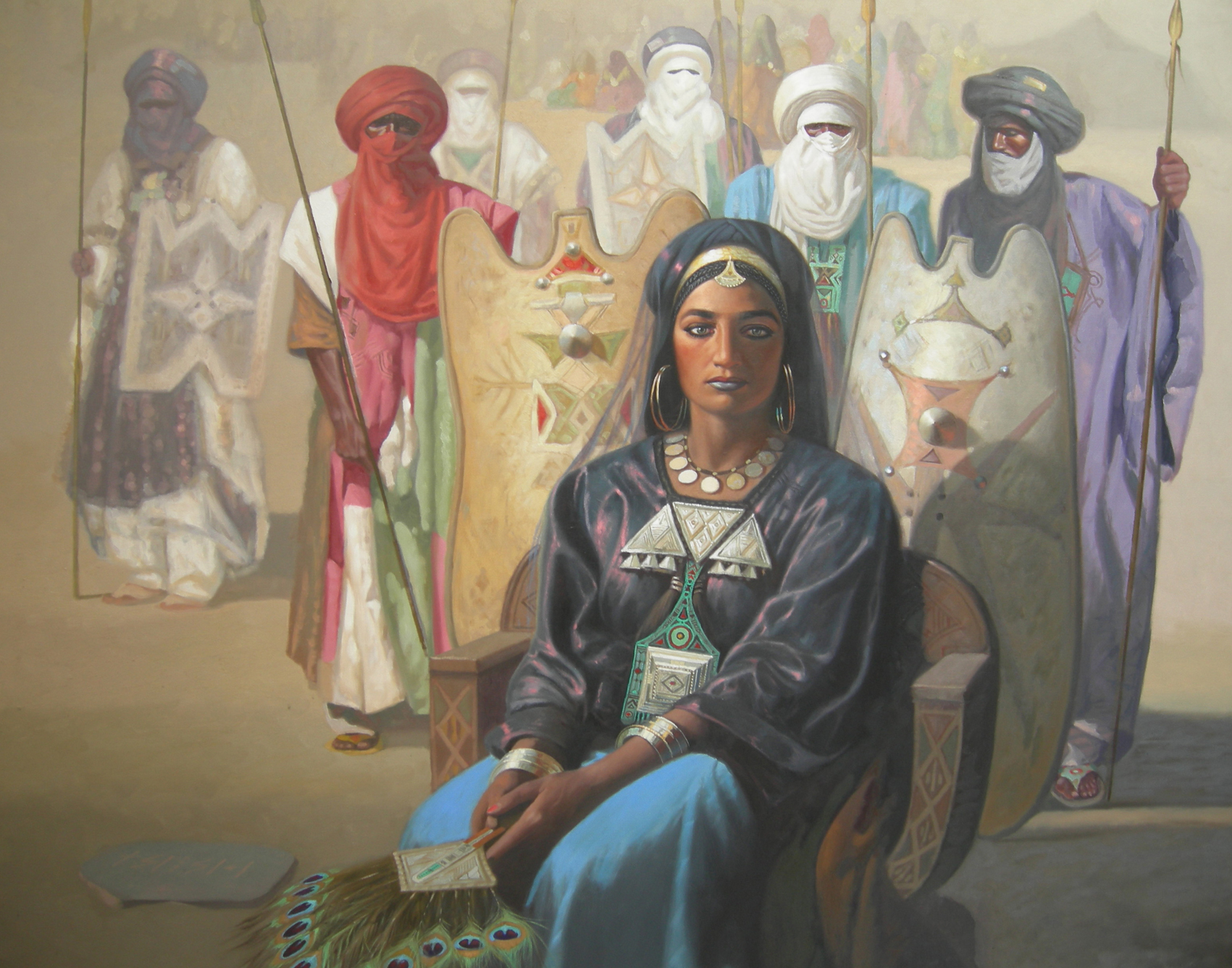

Tuareg Communities Of The Sahara

Among many Tuareg groups in the Sahara, descent and key forms of property follow the female line. Women often own tents, rights to camp sites, and herds that sustain desert life. Men veil their faces in public, while women move unveiled, compose praise poems, and teach the Tifinagh script. When marriages end, wives frequently keep the family assets and sometimes initiate separation. This blend of matrilineal inheritance and visible female autonomy challenged outsiders expecting strictly patriarchal desert societies.

Bribri Peoples Of Talamanca

For Bribri communities in the forests of Costa Rica and Panama, clans are matrilineal and women hold unique ritual and land rights. Only women can inherit family land, and only women may prepare the sacred cacao drink central to ceremonies. Children belong to the mother’s clan, which shapes social roles and obligations. That structure gives daughters a strong link to territory and tradition, tying everyday farming to spiritual work and conservation in ways that modern environmentalists have started to recognise.

Nagovisi Villages In Bougainville

In Nagovisi communities on Bougainville, women are central to landholding and dispute settlement. Descent is traced through the mother, and women manage lineage land, pigs, and compensation payments after conflict. Anthropologists describe them as key voices in negotiations over cash crops and mining, especially when projects would disturb ancestral ground. Rather than fitting a simple image of passive matriliny, Nagovisi life shows women actively steering how outside money and local obligations meet in gardens, meetings, and clan councils.

Umoja Women’s Village, Kenya

Umoja in Samburu County began in 1990 as a refuge for women escaping violence and forced marriage. Men may visit as guests, but only women and children live there, run the school, and manage tourism and beadwork cooperatives. Over time, the village has pressed local officials for land rights and inspired similar initiatives nearby. Historians and activists now treat Umoja as a living example of women building safety, income, and political voice by quite literally founding a new place to stand.