New Year’s Eve in the United States is a mash-up of customs borrowed from many places. From Scottish songs to Spanish grapes and Japanese noodles, these traditions crossed oceans and found new homes at midnight parties and family dinners. Most arrived with immigrants during the 1800s and 1900s, then spread through radio, TV, and social media. Today, millions join in without knowing the roots. Here are 10 global ideas Americans borrowed, with dates, places, and details behind them.

1. Fireworks at Midnight

Fireworks at midnight began long before Times Square. Gunpowder fireworks were invented in China around the 700s, then spread along trade routes to Europe by the 1200s. Immigrants brought the habit to U.S. New Year parties during the 1800s, and big civic shows followed. Today, cities like New York and Seattle light synchronized displays set to music, with safety rules that ban personal aerial shells in many states. The boom marks a loud break from the past and a bright start to the year. Fire codes restrict launch zones, and cities post start times so crowds can watch from viewing areas.

2. Singing “Auld Lang Syne” from Scotland

Singing “Auld Lang Syne” is a Scottish gift to American midnights. The poem was set down by Robert Burns in 1788 from older lines. The song spread in the United States after bandleader Guy Lombardo played it on live radio from New York in 1929, then on nationwide TV by 1956. Since then, stadiums, living rooms, and street crowds have used it for the midnight countdown. The title means “old long since,” a toast to friendships, shared stories, and the year just passed. Many families still cue the track right after the clock strikes 12, keeping the Scottish tradition alive across the States.

3. Making New Year’s Resolutions

Making New Year’s resolutions traces back to ancient promises. Babylonians around 2000 BCE pledged to return borrowed tools at the start of their year, and Romans honored Janus, the two faced god of doors, each January. Americans picked up the habit through churches and newspapers in the early 1800s; an 1813 Boston piece mocked faddish vows. Today, common goals list 10,000 steps, better sleep, or saving a set dollar amount by June. Dating goals helps people track progress. Teens often post progress check ins monthly to keep friends and classmates accountable through spring.

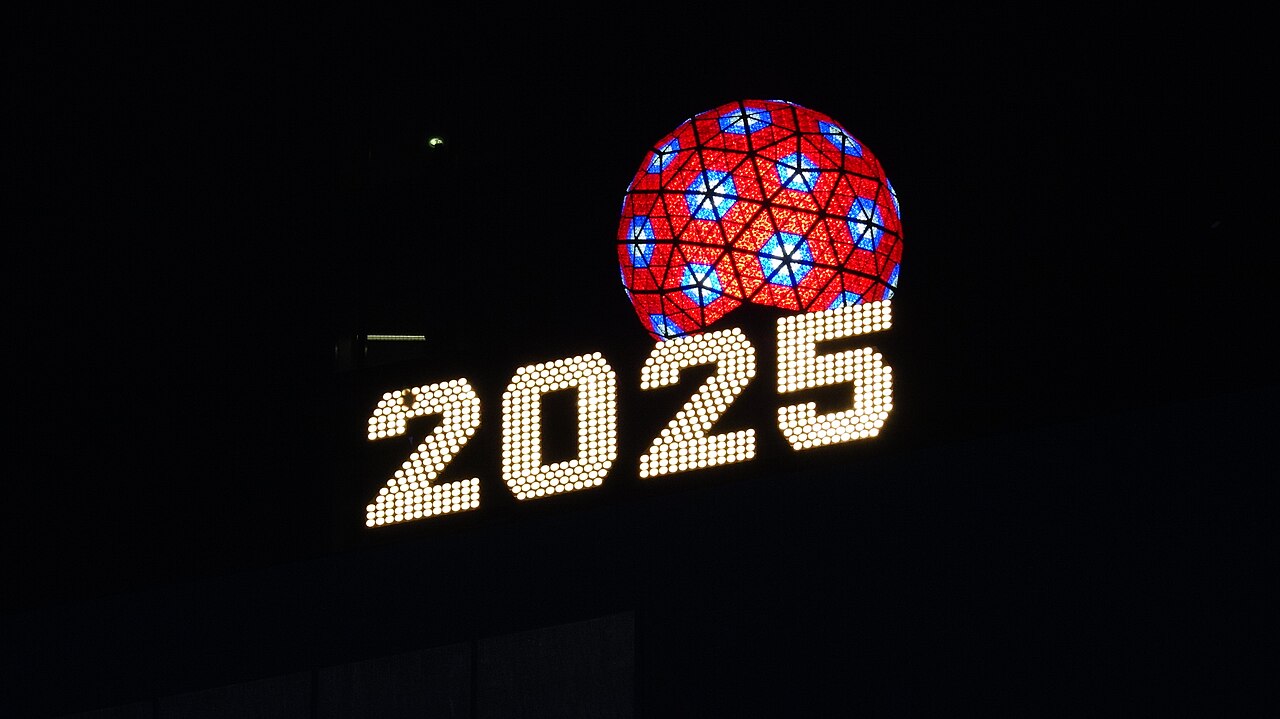

4. The Ball Drop’s Time-Ball Roots

The Times Square Ball Drop in New York borrows from 1800s “time balls” used in ports. The Royal Observatory at Greenwich began dropping a ball daily in 1833 so ship captains could set chronometers at 1 p.m. New York adopted a lighted version for New Year’s Eve in 1907, replacing noisy fireworks. The modern sphere weighs over 11,000 pounds and sits 470 feet up. The idea came from maritime timing, then became a city countdown watched nationwide. Millions now watch on TV and streaming at 11:59 p.m., following the 60 second descent to mark the exact change of year.

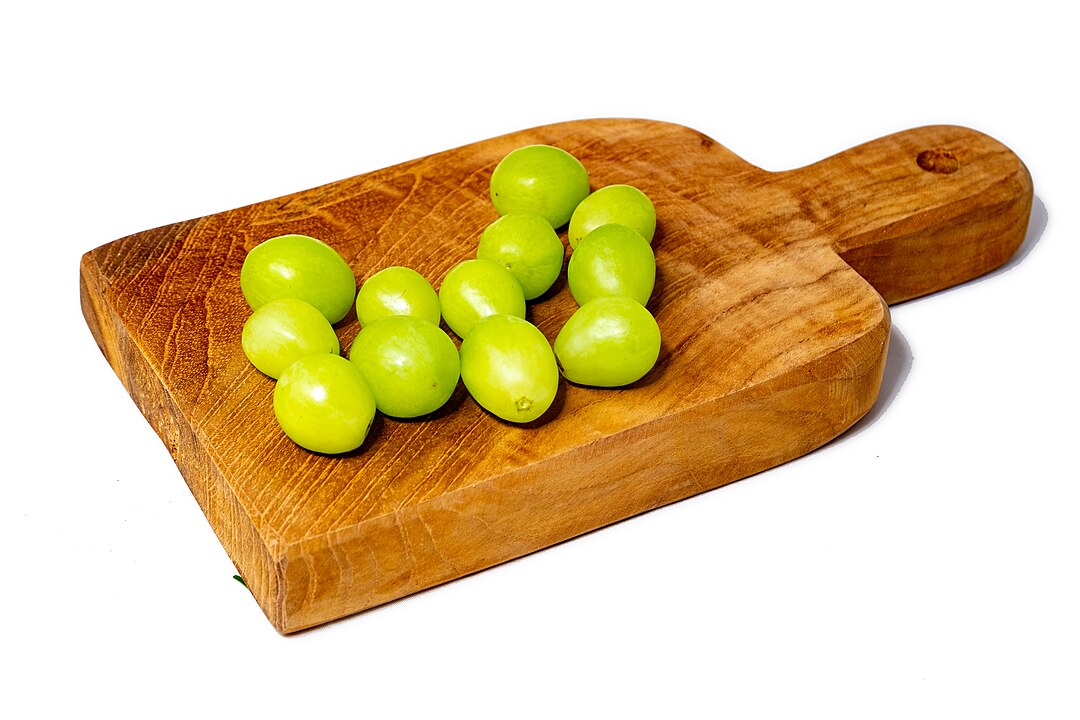

5. Twelve Grapes from Spain

Eating 12 grapes at midnight comes from Spain. In 1909, growers in Alicante promoted one grape for each bell strike at 12, a tradition called las doce uvas. Families across Mexico, Peru, and the Philippines later adopted it, and immigrants carried it to U.S. cities like Miami and Los Angeles. The rule is simple: finish all grapes before 12:01 for luck. Superstitions aside, it turns the countdown into a quick game that everyone at the table can join. Many households chill seedless grapes in small cups before 11:50 p.m. so every person gets exactly a dozen when the clock starts.

6. First-Footing and Hogmanay

First footing, a Scottish Hogmanay custom, says the first visitor after midnight sets the home’s luck. In many regions, a dark haired guest carrying coal, bread, or whisky is best, bringing warmth and food for the year. Scottish immigrants shared the habit in 1800s American mill towns from Pennsylvania to Michigan. Some families still send a neighbor to knock exactly at 12:05 a.m. The small gifts are symbolic, but the door opening makes New Year hospitality real. Teens can adapt it with hot cocoa or cookies, keeping the spirit while leaving alcohol out of the tradition at student gatherings.

7. Year-Crossing Soba from Japan

Slurping toshikoshi soba, meaning year crossing noodles, is a Japanese tradition that reached U.S. tables through Japanese American communities by the early 1900s. Records from the Edo period show families eating buckwheat noodles on December 31 to let troubles break easily. The long strands symbolize a long life. In Honolulu, Los Angeles, and Seattle, markets sell fresh soba on December 30 and 31. Many households now serve noodles before fireworks as a calm, warming ritual. Pairing the dish with green tea keeps the meal light while giving guests a focused moment to reflect on the past year.

8. Year-End Deep Cleaning

Year end deep cleaning, called osouji in Japan, influenced many American households that like a fresh start. Families clean on December 28 to 31, organizing closets and wiping door frames to clear dust before January 1. The habit spread here through Japanese schools and cultural centers in the 1970s and 1980s, then through online checklists. Teens adapt it by boxing clothes for donation and emptying backpacks. A tidy room on January 1 makes new routines easier to keep. Quick safety note: unplug decorations and use a step stool when reaching high shelves, since climbs cause holiday injuries.

9. Polar Bear Plunges

Cold water plunges on January 1 feel very American, but the habit grew with influences from Canada and Northern Europe. The Coney Island Polar Bear Club in New York formed in 1903 and still leads a New Year swim. Vancouver’s Polar Bear Swim began in 1920 and drew thousands by the 1970s. Many U.S. towns now jump for charity, timing the splash at noon to support local causes. Safety first: wear footwear and get cleared by a doctor if you have heart risks. After the plunge, volunteers hand out towels and hot cocoa, and warming tents help swimmers avoid chills when winds push below 32 degrees.

10. Ring Cakes and Vasilopita

Cutting a ring shaped cake for luck comes from Greece. Families bake vasilopita for January 1, honoring Saint Basil, and hide a coin inside. Whoever finds the coin is said to have good fortune for the year. Greek American churches in cities like Chicago and Tarpon Springs host public cuttings each New Year, slicing one piece for the house and pieces for guests. Some swap the coin for a wrapped charm to avoid chips and protect teeth at busy gatherings. Many hosts record who finds the coin and post the winner in the next church newsletter, keeping the tradition visible for younger families.