A calm living room can hide a panel full of shortcuts. Inspectors keep finding the same violations tucked behind metal doors and nearby boxes, many born from DIY fixes or legacy hardware tied to failure rates. The cure isn’t exotic; it’s basics done right: match breakers to wire size, keep splices in boxes, label circuits clearly, and use protection that trips when it should. Here are 10 problems pros still flag, why they matter, and the safer path forward.

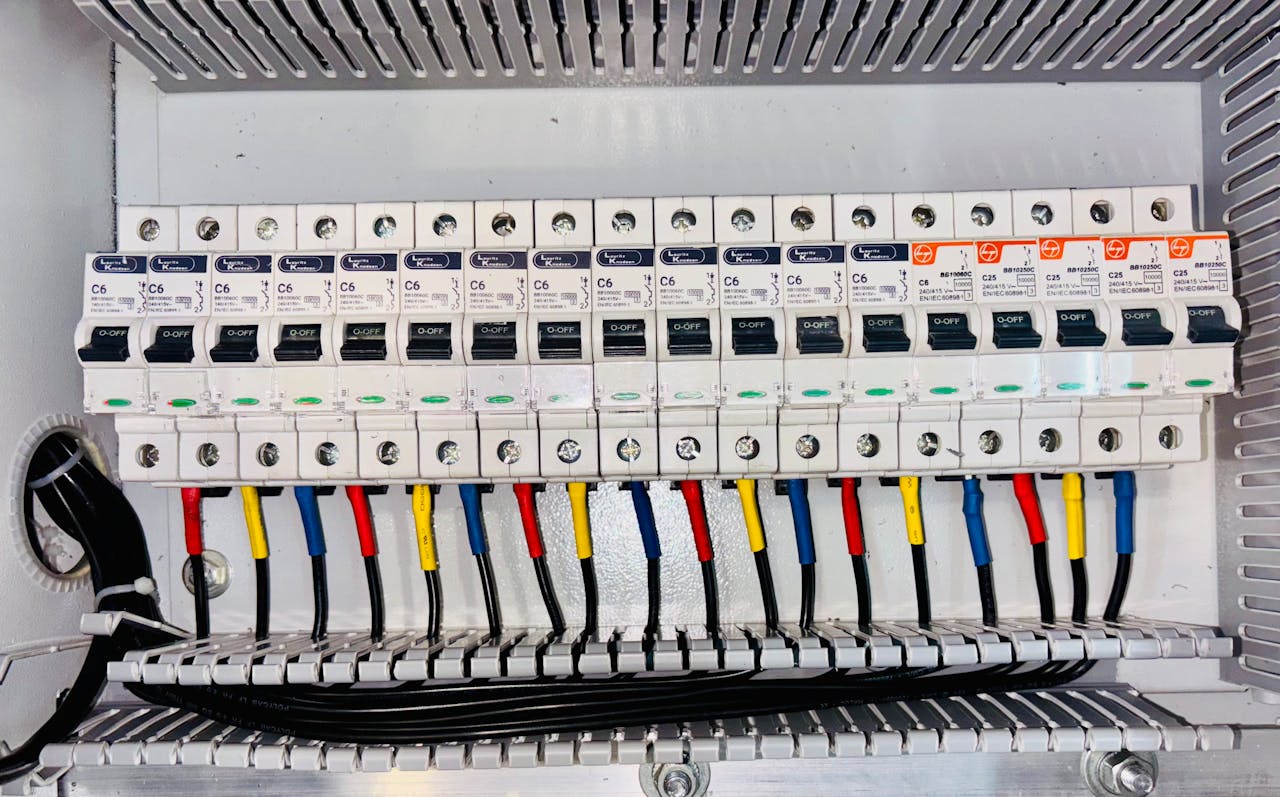

Double-Tapped Breakers In Crowded Panels

Two conductors crammed under a lug meant for one loosen over time. That uneven clamping raises resistance, heat, and the chance of arcing that chars insulation long before a breaker reacts. Most breakers are not listed for twin leads; a few are, and they’ll say so. Electricians either swap in a breaker rated for two wires or add a subpanel to gain spaces. It’s a small repair with real stakes, since many violations surface only during sale or insurance checks.

Oversized Breakers Swapped To Stop Tripping

A tripping 15-amp breaker doesn’t need a 20 or 30; it needs the real fault fixed or a new circuit for the load. Upsizing while leaving the same wire gauge invites overheating inside walls where no one can see or smell the danger. Codes tie breaker size to conductor and load, not convenience. The safe route is to reduce demand, correct shorts or loose connections, and add dedicated circuits where hair tools, space heaters, or EV chargers pushed limits.

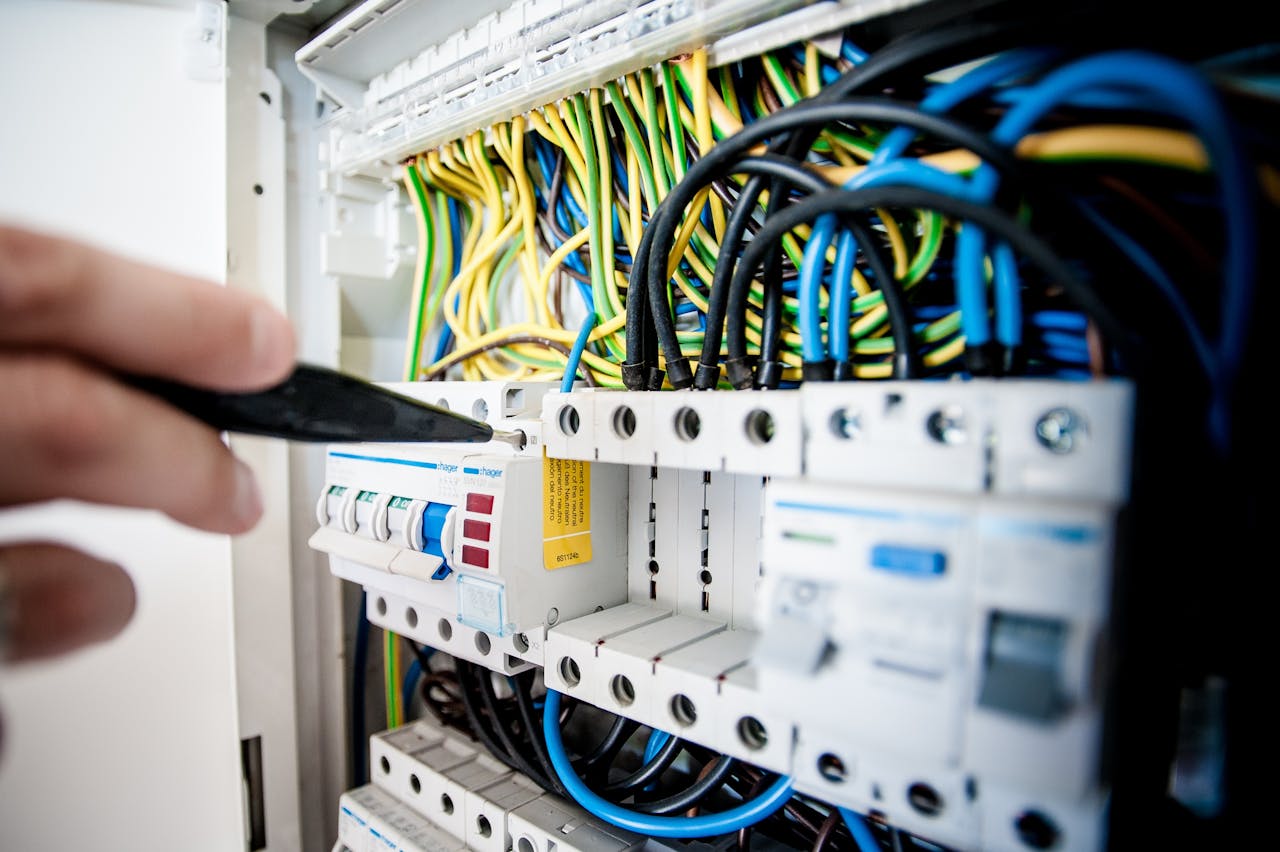

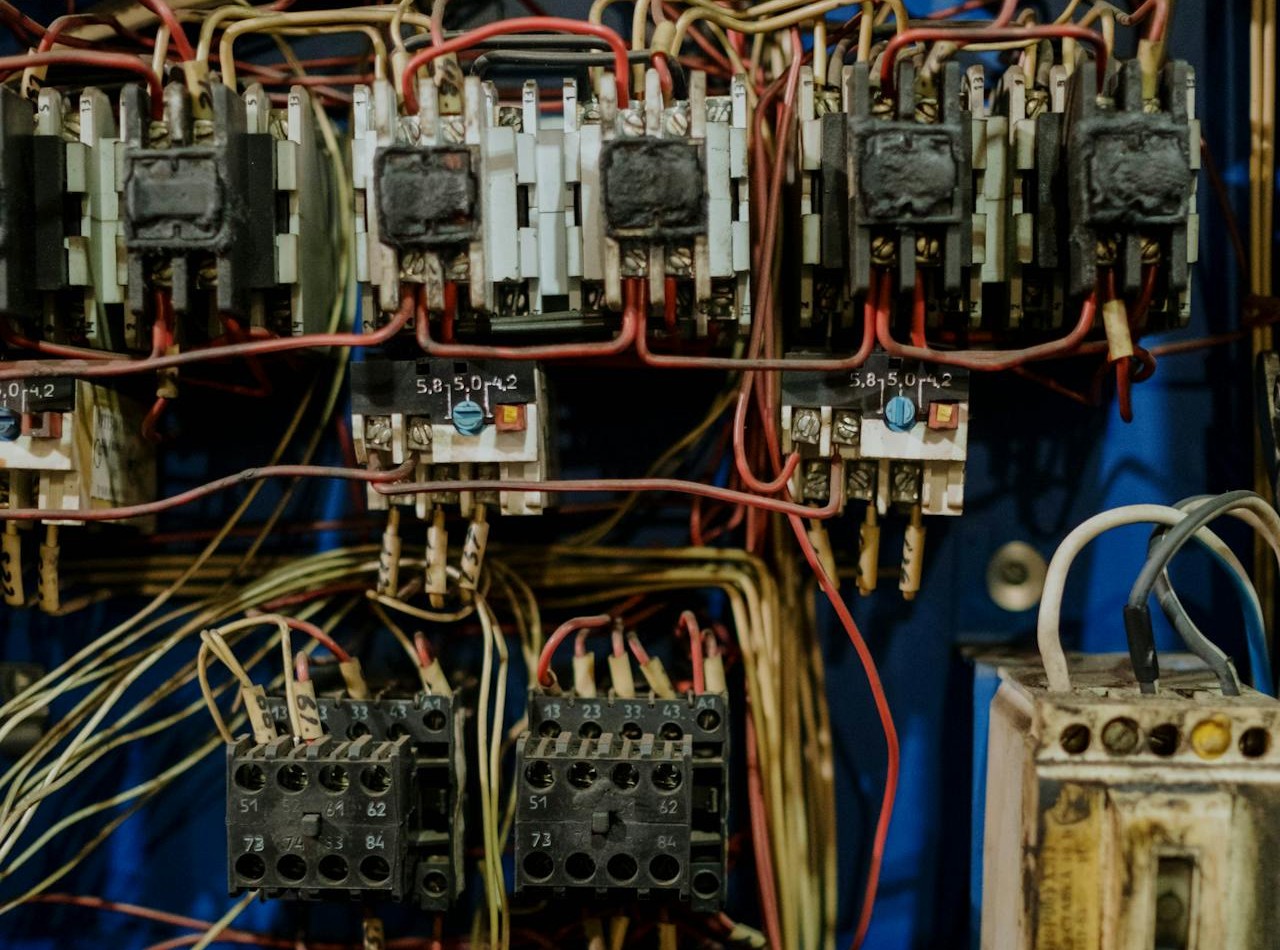

Federal Pacific Stab-Lok Panels And Add-Ons

FPE Stab-Lok gear has a long record of failed trip tests and fire links. The only thing worse than a suspect panel is a “modified” one. Owners sometimes force noncompatible breakers on the bus or use aftermarket parts to revive tired hardware. That violates listings and compounds risk. Modern codes do not allow new installations; pros recommend full replacement rather than patchwork. A new, listed panel with torque-checked terminations and a clean directory lowers both hazard and hassle.

Splices Outside Boxes Or Buried In Cavities

Splices belong in listed junction boxes with covers, clamps, and space for conductors. Twists wrapped in tape behind drywall or in attic insulation are illegal and dangerous. Loose joints build heat and can ignite nearby material before an overcurrent device ever knows. The fix is simple: add an accessible box, use rated connectors, and respect box-fill limits. Hidden convenience is not worth a hidden spark, especially where renovations sealed problems out of sight for years.

Aluminum Branch Circuits With Wrong Connectors

Solid aluminum branch wiring from the late ’60s and early ’70s needs aluminum-rated devices, proper transition fittings, and sometimes antioxidant compound. Landed on copper-only devices or tied to copper with standard wire nuts, the joint corrodes and loosens, then runs hot. Inspectors call out mismatched terminations; electricians replace devices with CO/ALR or use approved Al-to-Cu connectors. Anything else is a slow failure that starts at a shiny screw and ends in a blackened box.

Knob-And-Tube Extended With Modern Cable

Historic knob-and-tube lacks equipment grounding and its insulation grows brittle. Splicing modern cable directly to it without a box, or “grounding” it to a pipe, doesn’t make it safer; it makes it unpredictable. Many insurers exclude it entirely, and most codes forbid extensions. Safe plans involve replacement with grounded cable, proper junctions, and documentation of abandoned runs. If preservation matters, leave K&T isolated and de-energized, then rebuild circuits that meet today’s load and protection.

Unlabeled Or Misleading Circuit Directories

A directory that reads “lights,” “plugs,” or “Ben’s room” on half the breakers isn’t just messy; it’s unsafe. Workers need to know exactly what goes dark when a handle opens. Mislabeled circuits can leave energized conductors in a wall someone believes is dead. Electricians rebuild directories with specific room names and equipment calls, test each handle, and print labels that stay legible. During emergencies, clarity turns a rushed shutdown into one clean, controlled step.

Bypassed GFCI Or AFCI Protection

Tripping annoyances lead some owners to swap GFCI outlets for standard ones or to wire around GFCI/AFCI breakers. That strips shock and arc protection from kitchens, baths, garages, and bedrooms. The fix is targeted: diagnose shared neutrals, bootleg grounds, or damaged cords causing nuisance trips, then restore listed protection where water or cord damage lives. Safety often lives in milliseconds; these devices buy them and meet code where it matters most.

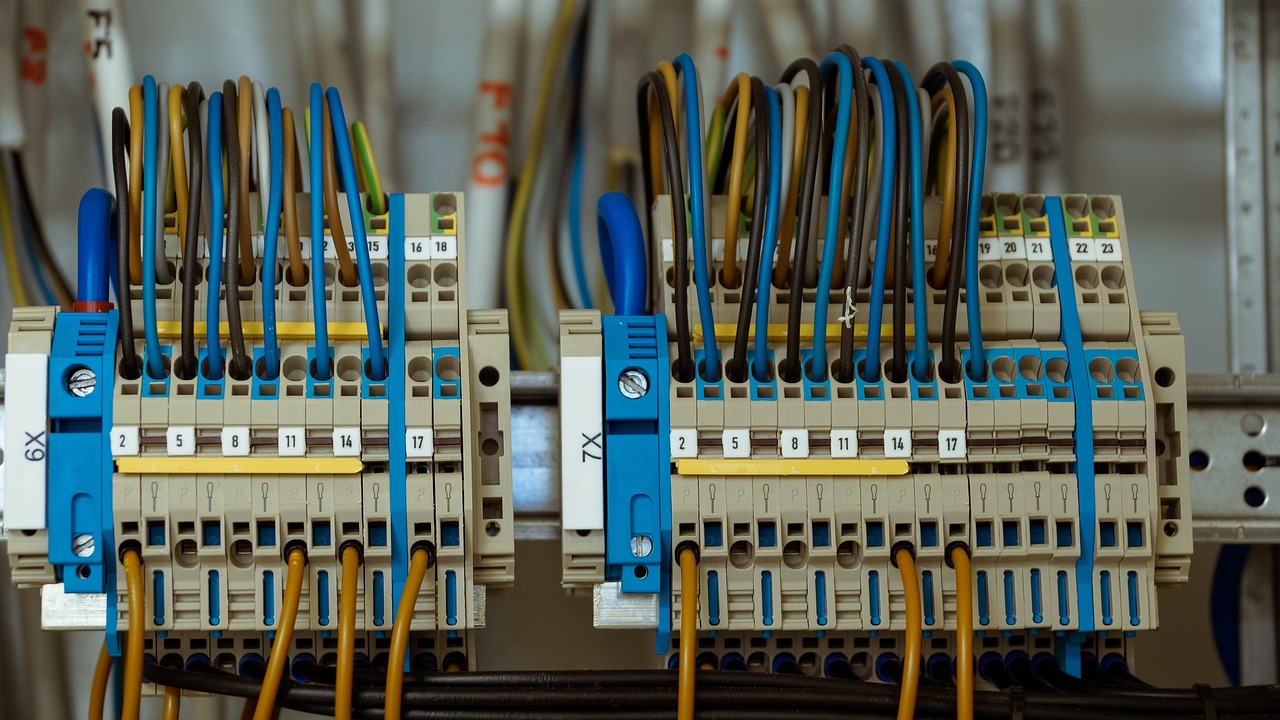

Overcrowded Boxes Beyond Code Fill

Boxes have cubic-inch limits tied to conductor count, device size, grounds, and clamps. Cramming extra splices into a box already at capacity scrapes insulation, traps heat, and leaves no room to work safely. Overfill shows up behind switches and lights where additions piled on. Proper work upsizes the box or adds another, uses listed connectors, and keeps grounds pigtailed and neat. Space isn’t cosmetic; it’s what keeps insulation intact and connections cool.

Extension Cords As Permanent Wiring

A cord is a temporary bridge, not a branch circuit. Running one through a wall, under carpet, or along baseboard as a substitute for a receptacle violates code and sidesteps overcurrent protection and abrasion ratings. Staples flatten conductors, hidden damage accumulates, and load creep turns warm into hot. The cure is dull but right: add receptacles on a permanent circuit, spaced per code, then retire the cord to weekend duty where it belongs.