Across the United States, whole communities vanished almost overnight so water could be stored or weapons could be tested. Farm towns, rail depots, and quiet crossroads were emptied on government timelines, not their own. Families boxed up lives that had taken generations to build, then watched water rise or fences go up behind them. Today, low reservoirs, guided tours, and reunion picnics hint at what was left behind: streets without houses, churches without congregations, and a lingering debate over what progress is worth.

St. Thomas, Nevada

St. Thomas began as a Mormon settlement at the meeting of the Muddy and Colorado rivers, later growing into a small desert town with farms, shops, and a school. When Hoover Dam went up, residents knew the water was coming but not how it would feel to watch their streets drown. They sold land, burned empty homes, and left graves behind as Lake Mead rose. Drought now exposes cracked foundations and paths, turning the lakebed into an open air reminder of what the reservoir replaced.

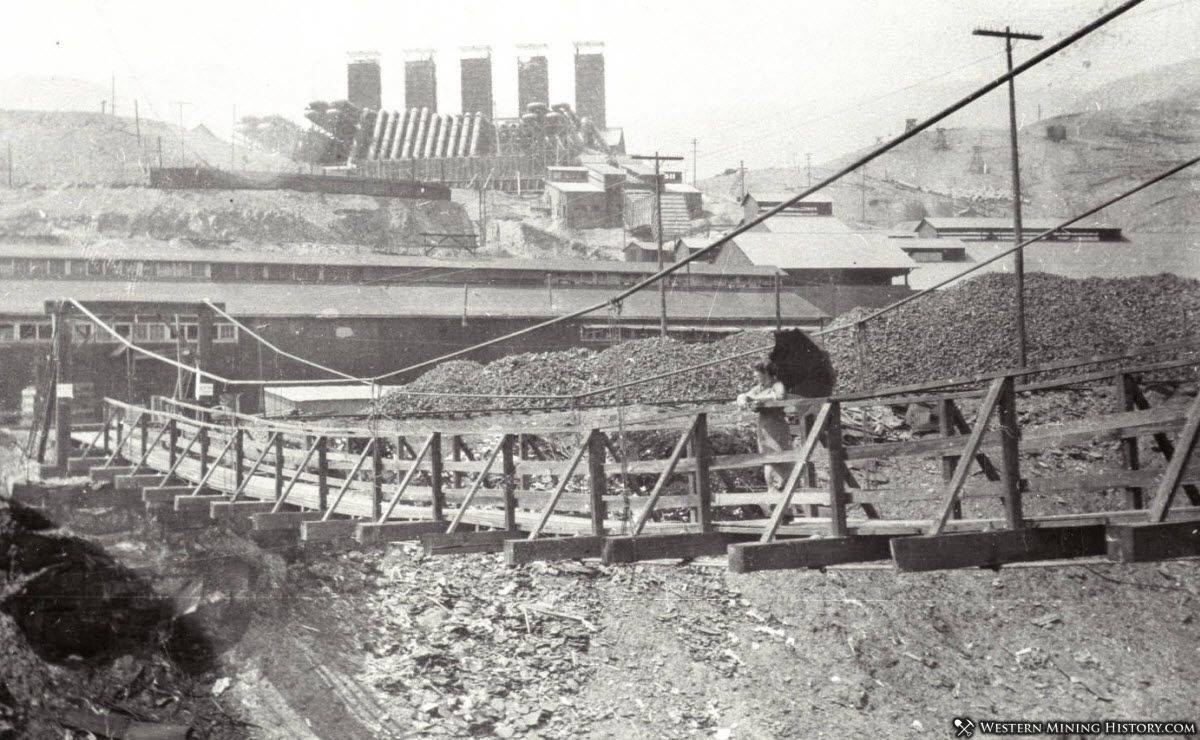

Kennett, California

Kennett was once a loud copper boomtown in northern California, packed with saloons, smelters, and a rail line threading the canyon. By the time Shasta Dam was planned, the mines had faded, but hundreds of people still called the town home. They watched the government buy properties and close the post office, then saw lake water slowly cover streets that had once held parades and payday crowds. In deep droughts, brick, timber, and old bridge abutments emerge, hinting at a city still sitting roughly 400 feet below the surface.

The Quabbin Towns, Massachusetts

In central Massachusetts, the Swift River Valley held the towns of Dana, Enfield, Greenwich, and Prescott, each with schools, mills, and social clubs that assumed they had a future. When Boston needed more drinking water, lawmakers decided the valley itself would become a reservoir. On one April day in 1938, residents were officially told their towns no longer existed, at least on paper. Houses were burned or moved, graves relocated, and roads abandoned. Stone walls and cellar holes in the woods above Quabbin now do the quiet work of remembering.

Old Bluffton, Texas

Old Bluffton sat along the Colorado River in Texas Hill Country, a small hub for ranchers, pecan growers, and travelers making river crossings. Buchanan Dam promised power and flood control but demanded higher ground. Residents jacked up houses onto wagons, moved headstones, and built a new Bluffton uphill, leaving the original town site to the rising lake. When long dry spells lower Lake Buchanan, foundations, fence lines, and the faint grid of streets reappear. Locals can point to where main street once ran, even as fishing boats idle nearby.

Loyston, Tennessee

Loyston grew from a rural crossroads on the Clinch River into a modest community with churches, a school, and farm supply stores that anchored surrounding hills. The Tennessee Valley Authority chose this stretch of river for Norris Dam, which meant the town’s future lay under water. Families posed for government photographers as they packed wagons and trucks, then watched their community disappear under Norris Lake in 1936. Today, divers and sonar find chimneys and foundations below the surface, while a highway marker onshore does the talking Loyston no longer can.

Willow Grove, Tennessee

Willow Grove sat in a fertile Cumberland River valley, framed by its namesake trees and a rhythm of school days, church meetings, and mill work. When the Dale Hollow Reservoir was planned during World War II, surveys made clear the town was directly in the footprint. Residents held farewell gatherings, then left behind classrooms, farmsteads, and the sound of the mill wheel. As lake levels shift, aerial photos and divers catch glimpses of old roadbeds and stone walls. A popular houseboat lake now floats above a place locals still call the town that drowned.

Butler, Tennessee

The town of Butler endured repeated floods from the Watauga River, rebuilding after each high water season and trusting the valley that had always held it. The Tennessee Valley Authority eventually concluded the river needed a dam, not sandbags, and Watauga Lake required the town’s entire footprint. More than one hundred homes, businesses, and churches were relocated to create new Butler on higher ground. Residents held a symbolic funeral for the old town as water rose over Main Street. Reunions and a small museum now keep track of which porch once faced which direction.

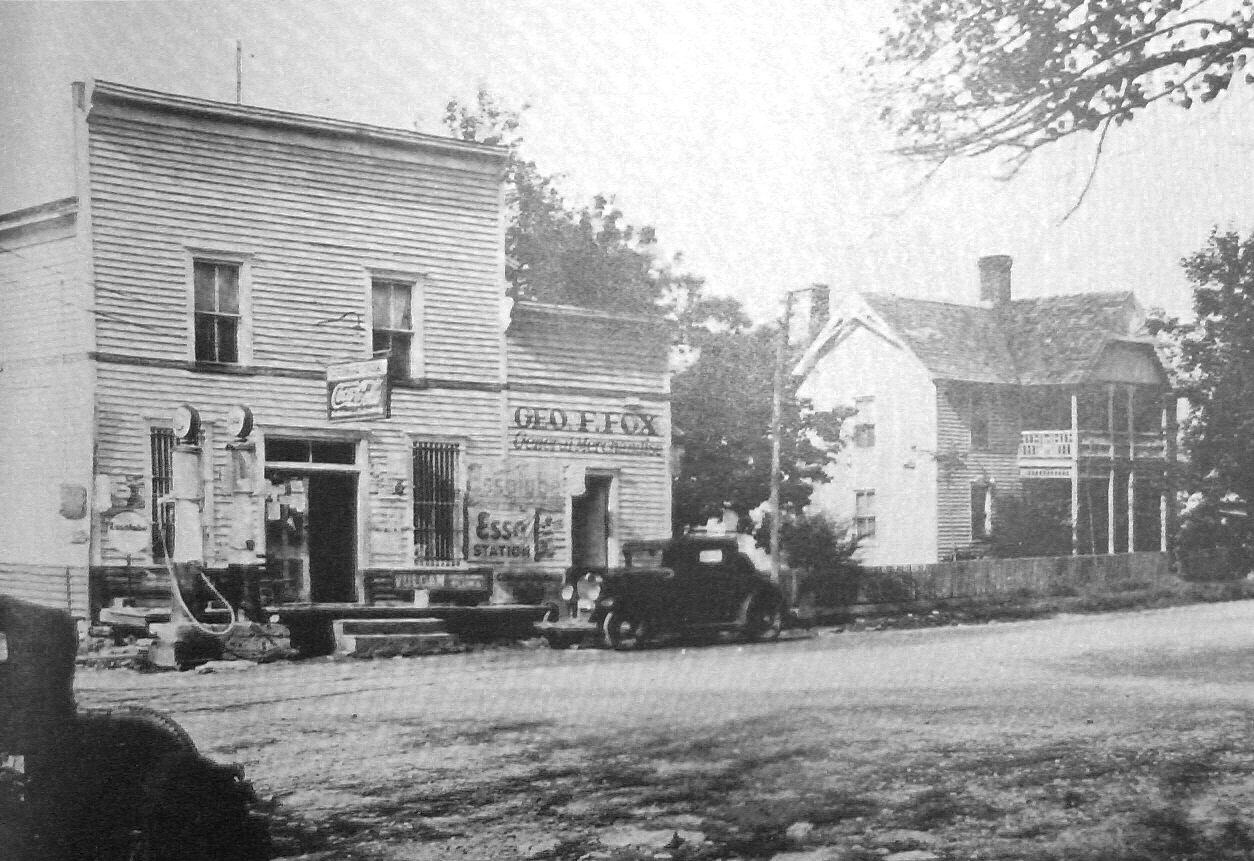

Ashokan Reservoir Villages, New York

High in the Catskills, the Ashokan Reservoir quietly supplies New York City with drinking water, its calm surface hiding fragments of several communities. Building the Olive Bridge Dam meant tearing out homes, farms, churches, and schools along Esopus Creek, then flooding much of what remained. Some neighborhoods were moved uphill, while others were simply erased as water backed up for miles. At very low water, old bridge abutments and road traces surface along the shore. For descendants, place names like West Hurley and Boiceville now refer to both memory and map.

White Bluffs And Hanford, Washington

Along the Columbia River, the farm towns of White Bluffs and Hanford grew fruit, raised livestock, and shipped crops by rail long before anyone spoke of plutonium. In 1943, federal officials arrived with orders and compensation offers, giving residents roughly 30 days to leave for a secret war project. Orchards were uprooted and farmhouses repurposed as offices at the new Hanford Engineer Works, which would fuel atomic bombs. Today, controlled tours pass decaying buildings inside a vast cleanup site, where contamination and history are tightly managed side by side.

Mercury, Nevada

Mercury began as a military style base camp in the early 1950s, built to house the flood of workers arriving at the Nevada Test Site. For decades it held dormitories, a movie theater, bowling alley, shops, and a bar where scientists, engineers, and soldiers unwound between nuclear detonations. When full scale testing halted in the early 1990s, the town’s purpose evaporated. Most facilities now sit quiet behind security gates, with only a small rotating staff remaining. It is a company town without a public, aging in the middle of the desert.

Doom Town, Nevada

Deep inside the Nevada Test Site, civil defense planners in the 1950s built a mock suburb that came to be known as Doom Town. It had furnished houses, power lines, cars in driveways, and mannequins posed as families at dinner or in living rooms. Nuclear tests such as Operation Teapot turned that staged neighborhood into a brutal science experiment on blast and heat. Photos of shredded walls and toppled mannequins gave the world an eerie glimpse of what an atomic blast could do to any ordinary street.

Bikini Atoll Village, Marshall Islands

On Bikini Atoll, far across the Pacific, a small village with a church, meeting house, and tidy thatched homes agreed to relocate so the United States could test atomic weapons. Residents were told the move would be temporary and for the good of humankind. Between 1946 and 1958, at least 23 nuclear tests scarred the lagoon, reef, and soil with intense contamination. Attempts at resettlement faltered as radiation levels remained unsafe. The community now exists in diaspora, carrying a ghost town not underwater, but in shared memory.